Editor's Note: This article was originally publised June 3, 2009

It’s every author’s dream to introduce a term into the mainstream lexicon, to condense a mountain of innovative research into a cultural catchphrase. Yet pervasiveness and longevity are also mixed blessings. Just as an idea is promoted to a slogan, it loses important nuances in its original meaning: “famous for fifteen minutes” and “form follows function” come to mind.

Robert Sommer’s Personal Space: The Behavioral Basis of Design was published in 1969. It enjoyed an estimable twenty-five printings, and its compact title concept caught on and found its way into diverse realms, from architecture curricula to legal discourse (pertaining to sexual harassment and abortion-clinic picketing lawsuits). The notion of an invisible but perceptible security zone or spatial bubble surrounding an individual became widely understood by laypeople. The phrase “You’re invading my personal space” became a key verbal expedient for siblings of a certain generation.

How does a popular term’s derivation, and even its creator, end up forgotten by the same people who regularly and unconsciously dispense it?

Let’s start with the man. Robert Sommer was Chair of the Psychology Department at the University of California, Davis, when Personal Space was published. In his long association with that institution he has held an astonishing three additional chairs, in Environmental Design, Rhetoric and Communication, and Art. This polymath capability indicates Sommer’s breadth of interest and research, apt for an author whose book would itself cross categories and audiences. The intellectual ferment of the time must be recalled; the pop intelligentsia was eating up works that synthesized subaltern findings from parochial disciplines into Big Ideas. This was the time of McLuhan’s War and Peace in the Global Village, Levi-Strauss’s Structural Anthropology, Toffler’s Future Shock. It’s notable that Personal Space broke through to the mainstream at least in part because it was not published by a university press but by Spectrum, an imprint of Prentice-Hall.

The origins of this work are as curious as its arguments are intuitively rational. Sommer conducted the research that would result in the book over the course of a decade, and his humanist mission solidified in a huge mental hospital in a remote area of Saskatchewan, Canada, where he worked under Humphry Osmond, the British researcher who used hallucinogenic drugs in his pioneering psychiatric studies, and indeed coined the term “psychedelic.” Osmond’s work there addressed not only the therapeutic possibilities of psychotropic drugs, but also the effects of the designed environment on people. Osmond devised other terms that Sommer would use throughout his own research, such as “sociopetal” and “sociofugal” — spaces set up to cause people to instinctively want to converge, or flee. The hospital was decidedly the latter, as Sommer wrote: “The building violated Florence Nightingale’s first canon that a hospital do the sick no harm...Osmond and I decided that changes in the physical milieu would benefit both patients and staff. When we attempted to learn about the connection between architecture and behavior, we were surprised to find out how little information was available.”

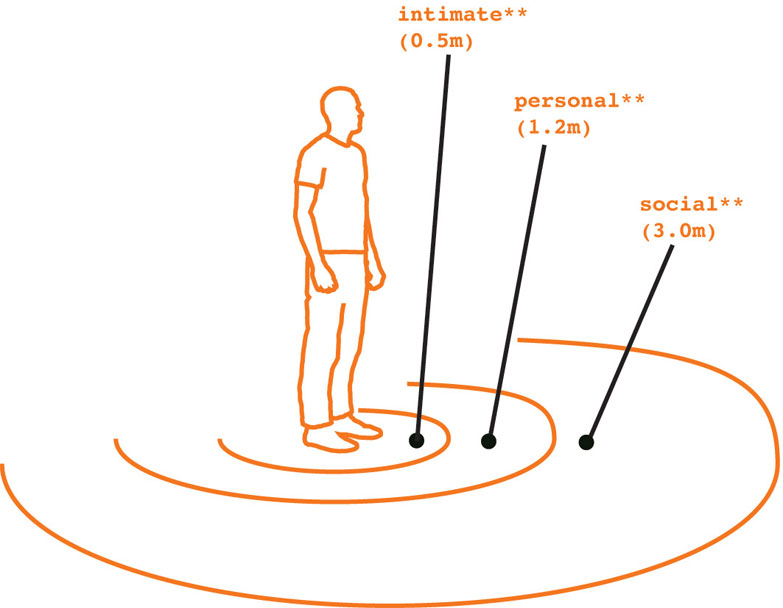

Sommer would synthesize current research from a wide array of disciplines including sociology, communication, psychology, perception, criminal and carceral studies, education, animal behavior, architecture, and urban planning. But it was his direct observation of how people behave near each other — often using himself and his students as agents for provocation of unwitting subjects in experiments — which revealed the invisible factors that regulate human proxemics to be commonsense. In the reading we recognize these behaviors because they are undeniably ours, belonging to the most deeply seated, reactive parts of our brains. Sommer conveyed that even modern people inhabit and protect space like animals and members of territorial tribes; the book is full of terms from anthropology and animal behavior study like “attack, “defend,” “invade,” and “victim.” An exemplary passage describing these innate, universal behaviors (with cultural factors imparting some distinctions) still has the power to surprise upon the recognition that these “victims” and “invaders” are, under similar conditions, the readers themselves: “There were wide individual differences in the ways the victims reacted — there is no single reaction to someone’s sitting too close; there are defensive gestures, shifts in posture, and attempts to move away. If these fail or are ignored by the invader, or he shifts position too, the victim eventually takes to flight.”

Many people have at least a basic (and intuitive) knowledge of what the phrase “personal space” means to them socio-spatially. But less understood is a subtler second meaning Sommer imparted to the term: “All people are builders, creators, molders, and shapers of the environment; we are the environment.” This much more nuanced connotation is where the rich potential for Sommer’s influence on design practice still lies, and it is from this philosophical position where some protégés have departed the academy and applied his theories in the private sector.

The design consultancy IDEO, for example, would not have the same service profile it does without Personal Space, due to the influence of Jane Fulton Suri, a human factors psychologist and IDEO creative director. Fulton Suri found the book at age nineteen studying psychology at the University of Manchester in the late 1960s, and based her undergraduate thesis on it; today she admits the book was a “key moment in my development and realization of what I might do.” Along with the social upheaval at play in those years, the psychological effect of “the whole urban environment was in question,” yet her interest in this kind of psychosocial research as it pertained to the built environment was anomalous for both the psychology department and the architecture school, where she also studied. Fulton Suri moved to the United States to study at the University of California at Berkeley, where the research of Clare Cooper Marcus, who would later author the popular book House as a Mirror of Self, was gaining currency.

In its environmental design practice, IDEO’s feted “human-centered” approach derives its observational technique from Sommer’s methodology. Yet in this Fulton Suri points up a curious fact about the legacy of Personal Space: IDEO has a competitive advantage due to the overall failure of Sommer to sufficiently influence spatial design practice. “My experience is that [Sommer’s work] still isn’t integrated, in large part due to [architecture’s] business model. Anything beyond programmatic basics aren’t followed up on. We do remedial work by pointing out bad environments.”

Another company with direct lineage is Envirosell, headed by environmental psychologist Paco Underhill, and whose research director, Craig Childress, is a former student of Sommer. Note the methodology statement from Envirosell’s web site: “Combining traditional market research techniques, anthropological observation methodologies and videotaping, Envirosell has established its reputation as an innovator in commercial research and as an advocate for consumer friendly shopping environments and packaging.” This description epitomizes the kind of observation-based, cross-disciplinary spatial research practice Sommer pioneered.

As Fulton Suri hinted, another key context for Sommer was the growing backlash against architectural modernism, especially in its associations with the International Style and Brutalism. The pervading influence of European modernism was in high critique during the era, as seen in numerous books including the influential The Hidden Dimension (1966) by Edward T. Hall, which cites the early research done by Osmond and Sommer in Saskatchewan. Through the observations of how such spaces were actually used by inhabitants and visitors versus the idealistic but essentially inattentive designs of their architects, these critics assailed the psychological and sociological effects of programmatic supermodernism. As Sommer wrote on the first page of his next book, Tight Spaces: Hard Architecture and How to Humanize It (1974), “The obvious conclusion is that San Quentin, Pruitt-Igoe, and the Irvine Campus of the University of California should never have been constructed in the first place.” Even by then, two years after its controlled implosion, the vast Pruitt-Igoe housing project in St. Louis (designed by Minoru Yamasaki, who also contributed his vision to the World Trade Center) was already the symbol of the abject failure of this kind of “hard” modernism.

An obvious line of inquiry regarding the longevity and applicability of Sommer’s book regard not so much how physical spaces themselves have changed, as to the degree our perception and concepts of place have been exploded in the digital era. I went to Sommer himself to solicit his thoughts on the subject. Now retired, Robert Sommer is still inexhaustibly fascinated by the implications of his research in a spatially and conceptually morphing society. “The main changes in interpersonal distance that have occurred in the past 40 years are the result of the digital age,” he wrote via email. “In public and even private settings, you cannot avoid people with cell phones […] or text messaging a distant person. Shortly before I retired, I started physically invading the space of people using cell phones. I didn't proceed with this study as I no longer had students to extend the research and I was doing other things.”

He proffers a challenge for today’s design thinkers and practitioners: “I believe that research on interpersonal spacing in the digital age is important and should be the subject of systematic research.” Sommer cites numerous other avenues at the inception of exploration: the interpersonal spatial dynamics of virtual reality, as researched by James Blascovich at the University of California, Santa Barbara; the physiologically driven peripersonal space concept articulated by mother-son team Sandra and Michael Blakeslee in their book The Body Has a Mind of Its Own; the increasingly revelatory findings of evolutionary psychology. Ever a synthesist, he holds other cross-disciplinary thinkers in the highest regard. “I greatly admire E. O. Wilson's book Consilience,” says Sommer, “and believe that a Darwinian functional framework can lay the basis for fruitful theories of interpersonal distance.”

The time is right for Robert Sommer to reintroduce his ideas to the world. Think of the increasingly sophisticated approaches to user interfaces and experience design, phrases which de facto are relegated to contexts of electronic displays and digital architectures; physical milieu scarcely get as much design consideration as immersive virtual environments. A recent study in Perception finds that listening to music on headphones alters our sense of sociospatial relations. Until these more contemporary strands of inquiry result in a truly new analysis of how we perceive our interpersonal zones today, Personal Space is now available in a new edition, with some additional commentary by Dr. Sommer, from Bosko Books in the UK.

Comments [17]

"where's the beef?" (a lovely phrase from the past also used non-stop in the 80s and then promptly left on the dustbin of history)

06.29.09

06:10

Check out Whyte's delightful The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces from 1980 or its companion film from eight years later if you want to see the joys of Sommer's brand of design thinking in action.

06.29.09

11:06

Excellent and very timely discussion. I think the issues of design and personal space are critical in today's personal-device-filled world. (I've also been intrigued by the construction of an implied personal or intimate space in printed media whether large scale bus shelter posters or small books as private objects.)

I am curious, though, if you have further thoughts on why the author of a concept becomes disassociated from the concept (or phrase) itself. In this case, I suspect that "personal space" seems like such a deep, bodily felt and natural concept that it's hard to imagine there was a generating author in the first place. Is it a triumph or a disappointment to develop something that dissolves so thoroughly into the cultural mainstream?

06.30.09

09:09

Also, I wish there was video of Sommer "physically invading the space of people using cell phones." Who says scientific research can't be fun?!

07.01.09

01:54

1. Is the use of the book in architecture curricula as noted by the poster a recent phenomenon, or was the book's popularity framed by a moment in time?

2. Is the work actually "intuitively rational" or is it based upon a peculiar moment in time, modernism and late modernism up to the 1970's, that had a predilection to ascribe enduring behavioral patterns to enduring patterns of form.

3. Are we sure that the hospital design referred to in Osmond's research was actually as bad as they thought it was? What were the control factors of their research? For instance, a hospital designed in the 1920's, by it's very newness might have created a therapeutic effect while the same hospital ill-maintained and poorly managed could induce the opposite. The variables are so enormous as to make simplistic deductions about space and experience questionable (though I assume Sommer is not simplistic).

4. Part of the reason Sommer's work may not be so well known at this point is there has been a lot of research which disputes the notion of universal behaviors in relationship to space. For instance, Katharine Bristol in "The Pruitt-Igoe" myth clearly describes a whole host of management, political, policy, racial, and economic factors to the failure of this iconic project, leaving one to wonder if the modern architecture and the form had as much to do with the failure of this project as first blush behavioralism would have one believe.

5. I agree as stated in the post that it is the everyday notion of Sommer's theories that are most relevant today, in essence the idea that people are active creators of their environments. This is territory explored by all sorts of French theorists writing before and after Sommer. Few of them offer too many clues with regard to "professional" design practices or fixed notions about form. That is because few were actually interested in design; they were more interested in social relationships and change.

6. This of course brings us to the environmental practice of IDEO which is in part influenced by the observational theories of Sommer. For me the interesting thing about IDEO's environmental practice is the fact that they make astute observations about places and things and make proposals for their mediation which are at times quite interesting. Yet, they actually never really implement anything environmental beyond ephemeral exhibit and show designs. In essence there is not much actual architectural or urban design risk in their practice. As a business model it is brilliant to concentrate on the conceptual but as a design model and an urban design model this lack of substantive committment to making through time is quite lacking in physical substance. In a different way the same is true of Holly Whyte, also mentioned in the post. The critique and observation of public space is profound but the actual making on the part of Project for Public Places is largely forgettable. Perhaps this also raises another reason why Sommer is not so well known, social science is great at framing issues and interpreting space but not necessarily great at either predicting environmental design success or assisting in the creative and making process which seems to demand additional perspectives and tools.

Sommer, as well described by the poster, clearly defined through research some interesting tools that describe some variables and techniques that are of use to the designer. But they seem very bound to the millieu in which they were created and less relevant to today's world then the author suggests.

In this last regard it is useful to remember that experience design, far from being solely a tool of the digital world as suggested (and cited without reference from Wikipedia: see definition of experience design - compare "...In the broader environmental context, there is far less formal attention given to the design of the experienced environment, physical and virtual — but though it's unnoticed, experience design is taking place." to the poster's last paragraph.) in fact has a rich history and relationship to the physical. The experience economy as an idea goes back more than three decades and has been thoroughly integrated into environmental design and architecture practices at all levels. Certainly not all these "experiences" are successful and some of the successful ones, like Disney World are nevertheless boring to many precisely because one is so clearly manipulated. The intangibles of the nexus between design and behavior are as complex and uncertain today as they were when Sommer wrote his book, which may explain why everybody knows what personal space is (thank you Professor Sommer), fewer can really define it, fewer design it, and even fewer remember who Sommer is.

07.01.09

02:17

07.01.09

08:18

07.01.09

11:52

Wonder when we "learn" that we have to keep some distance and give people "space." And when we forget or don't care about it any more.

Hi Ho!

VR/

07.01.09

11:48

Though I disagree with the detractors’ comments about the value of Dr. Sommer’s research, clearly his work—like any work—is bound by the particular circumstances of its origins. That applies to the limitations and biases of its originator, as well. One of the attributes of Personal Space that could ultimately be a mixed blessing was its popular appeal, which perhaps led people to think they got the thrust of the book and overlook its more delicate arguments. Or perhaps forego reading the book itself.

Nowhere do I claim that every argument of Personal Space is sound; that it is influential is difficult to deny, even as its mission is incomplete, and its legacy diversely interpreted. The need for this basic spatial literacy—among designers and anyone who uses designed spaces—is still keenly felt; as someone else has pointed out, the milk and sugar station at any given coffee house almost always provides a frustrating experience when more than one person is competing for it. We probably all have several experiences like that in any given day. It speaks to the underexplored and unfulfilled design potential in our everyday lives.

I thank Kevin Lippert for his objection to the implication of plagiarism in my piece, even if the commenter evaded using the word itself. My trade is also publishing, and I believe that this is the most serious allegation that can be directed at any writer—and not one to be casually deployed in an attempt to bolster an unrelated argument.

07.02.09

01:04

07.02.09

04:06

(2) The genericization of Sommer's term is the curse of success, isn't it? It applies to material design as much as theoretical terms: invent the zipper, the Exit sign, or the tailfin, and only the most conscientious DO readers will remember who you are. Martin Venezky's comment is sound - do a good enough job, and what you produce will appear natural and having always been there, certainly not an individual's 'invention'.

(3) It is interesting that the book's title is 'Personal Space' but Sommer himself uses the phrase 'interpersonal spacing'. It is not about the individual in isolation (modernism indeed!) but how space is socially produced. I don't have Sommer's book at hand, but I am wary of the claim that interpersonal space is fundamentally and adequately explained by reference to evolution, 'animal instincts' and the like. Cross-cultural evidence suggests great variability in body/space relations. It is too easy to overplay the psychological and downplay the sociological.

(4) From one comment: "it is the everyday notion of Sommer's theories that are most relevant today, in essence the idea that people are active creators of their environments." I have to disagree. What is most relevant is not the idea that people make their environments. Such an idea is basic and ancient. Sommer's contribution is showing (with actual evidence from empirical research) that people unconsciously produce, maintain, and reproduce interpersonal spatial patterns, patterns which are predictable given a constrained context. Thus one could say that people are for the most part passive creators (and consequently subjects) of their environments.

07.02.09

07:48

07.02.09

10:15

This happens on an unconscious level, and people attempt to maintain the proper distance by reflex. Drop someone from our culture into the Mediterranean area, where the normal personal space is about half that, and watch the fun.

See anthropologist Edward T. Hall's works on the topic, particularly the books _The Silent Language_ and _The Hidden Dimension_.

07.04.09

09:39

07.12.09

12:44

08.21.09

12:37

12.19.09

03:35

09.26.10

08:50