My introduction to Finland and its outsider design history came during a visit last December to MariMatic, a Finnish manufacturer of systems that collect trash and recyclables via pneumatic tube. Yes, tubes for trash.

I view waste management as a design problem, one that is still waiting for designers. Channeling the rich, stinking flow of discards from homes and businesses is considered a purely operations and maintenance issue. But the failure to design systems to manage this flow can be extremely costly, not to mention gross. Fortunately, things are changing. Cities are striving to meet higher standards for greenhouse gas emissions, air quality, and resiliency. Urban farms and green roofs have been part of the watershed/foodshed toolkit for a while. I predict that new strategies for wastesheds will follow—as we become increasingly aware of the environmental penalties imposed by truck-based trash collection, and of the inherent inefficiencies of trying to collect recyclables and organics (or implement volume-reducing unit-pricing schemes, sometimes referred to as “pay-as-you-throw” or “save-as-you-throw”) by slinging bags into rear-loaders.

Times Square in February, 2014 | photo by Jerusha Clark

I spent the last several years studying the potential of pneumatic tubes as an alternative to trucks with Benjamin Miller, a waste expert and senior fellow at CUNY’s University Transportation Research Center, Region 2. Last year we formed ClosedLoops to apply what we’ve learned to retrofitting the densest, most congested New York City neighborhoods with tube networks.

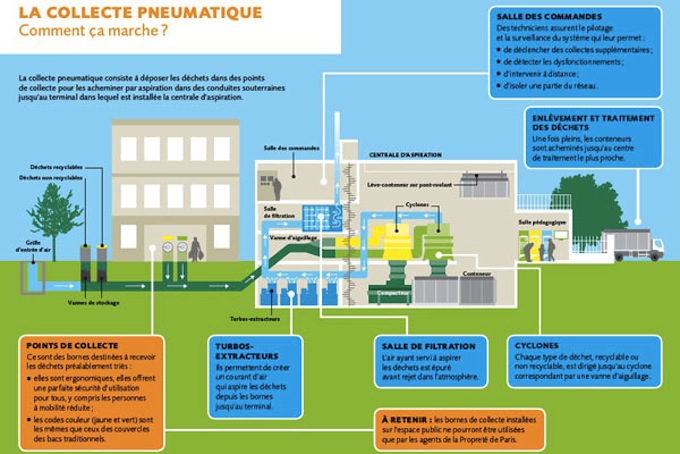

The basic concept is simple: users put waste or recyclables into separate inlets installed inside buildings or on streets or parks. When the reservoirs at the base of the inlets are full, vacuum pumps suck the source-separated materials through underground pipes to a collection terminal up to several miles away. There the trash, recyclables, or organics are compacted into separate shipping containers for transport to a processing or disposal facility. Like sewers and subways, these systems are expensive to build, but relatively inexpensive to operate.

Several thousand pneumatic systems are now in operation. Some installations, such as those in Clichy-les-Batignolles (in Paris’s 17th arrondissement) or Wembley (in Greater London) are in high-profile infill developments with strict standards for environmental quality. Others, like those in Seville and Copenhagen, are in historic city centers where truck access is difficult. In Stockholm, 400 separate facilities serve a quarter of the population. (A Swedish company, Envac, was the first to develop the strategy in the 1960s.)

Diagram of pneumatic collection plan for Clichy-Batignolles, Paris

Pneumatic inlet in Seville | photo by Benjamin Miller

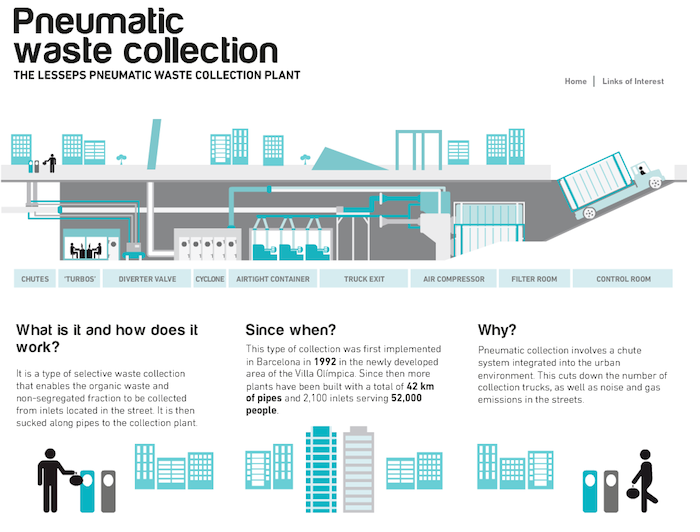

During the urban renewal that followed the 1992 Olympics, Barcelona developed a masterplan identifying areas to be served by pneumatic collection. There are now nine networks around the city (the first of which was built for the Olympic Village.) New high-rise cities in Asia, such as Sino-Singapore Tianjin Eco-city, China and Songdo in Seoul, South Korea, rely on tube collection. And in the Middle East, the largest system in the world is being installed at the Grand Mosque in Mecca. (More on that next time.)

System diagram from Barcelona municipal website

Alas, the idea hasn’t caught on in the US, yet. Our only municipal system was built forty years ago on New York’s Roosevelt Island, a utopian “new town in-town” masterplanned in 1969 by Philip Johnson and John Burgee for the NYS Urban Development Corporation.

Although the system has been in continuous operation for the last forty years (even during the recent hurricanes and blizzards), it has gone essentially unnoticed, viewed as an inconsequential techno-quirk with limited general applicability, like the aerial tram service that swings residents between the island and midtown.

Had Roosevelt Island not been perceived as a planning failure—before the first phase was complete the development agency lost its financing and the second phase of the high-profile plan was left unfinished—New York City might have taken note of its innovative pneumatic waste infrastructure, as Barcelona did of its new system in the afterglow of the Olympics. But with forty years of successful operations to its credit—and with New York’s current “Vision Zero” re-evaluation of street design for safety, aggressive housing development plans, and a pilot curbside food scraps collection program for composting and energy recovery just getting underway—this is the perfect time to reconsider pneumatic collection.

Automated vacuum collection plant on Roosevelt Island | photo by Gregory Whitmore

If the technology is being used all over the place why isn’t New York tubing up every time the streets are opened up for new infrastructure? The answer may have nothing to do with the strategy itself. As with any novel technique, engineers and designers must be able to understand how to incorporate it into an (often existing) design and administrators have to decide what standards it must meet and how it will interface with a city’s existing networks. Olympic Village-type greenfield developments with big budgets, autonomy, and license for innovation offer one way in. We would like to go directly to the next stage and see pneumatic collection deployed in existing neighborhoods as a community-improvement initiative built on public support engendered by reduced truck trips and green house gas emissions. The fact that Envac (the builder of the Roosevelt Island system) now has a successful portfolio of hundreds of operational facilities and is still building them all around the world says a lot about the potential of such systems, but a single major manufacturer is not enough.

We had heard about innovations made by a Finnish company, MariMatic, and about a huge R&D facility nicknamed “Legoland,” which they had built to test their latest designs. We were eager to have firsthand look for ourselves. What we found reminded me of Pekka Korvenmaa’s history of Finnish design: a geographically isolated outsider, new to the field, refining and recombining established techniques and successfully applying them in innovative and unanticipated ways. I wasn't expecting to find another outsider story …

In Part III: Denmark's LegoLand, not what you think.

We had heard about innovations made by a Finnish company, MariMatic, and about a huge R&D facility nicknamed “Legoland,” which they had built to test their latest designs. We were eager to have firsthand look for ourselves. What we found reminded me of Pekka Korvenmaa’s history of Finnish design: a geographically isolated outsider, new to the field, refining and recombining established techniques and successfully applying them in innovative and unanticipated ways. I wasn't expecting to find another outsider story …

In Part III: Denmark's LegoLand, not what you think.