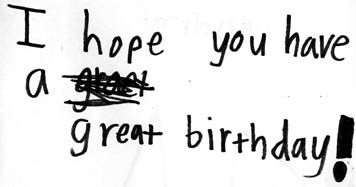

Every time I look at my son's handwriting, I find myself prognosticating about his future. Will Malcolm be good with his hands? Will his math skills lead him into science? Will his argumentative personality make him a championship debater? Will he follow his parents into design? Will he be happy?

Reading handwriting is an old art: graphology is one of the more articulated forms of divination, and handwriting analysis has long had the trappings of a science with its history and court experts. The assumption, of course, is that every hand is different, every stroke the sign of an individual's quirks and personality. It hasn't always been so.

In America, the idea of a prescribed form of handwriting was championed by Austin Palmer over a century ago. While working for the Iowa Railroad Land Company in the 1880s, he observed that clerks doing ornamental penmenship "flourished all capitals with a free-arm swing, with the arm completely off the desk." They used an entirely different movement to write normally. "The most swift and tireless penmen appeared to keep the arm on the desk at all times and formed their letters with little or no motion of the fingers — a free and tireless style of penmanship." Palmer realized that his "muscular movement writing" was something that could be taught and that advertising his "system" could help him to change the world — that everyone's handwriting could be efficiently executed while basically looking the same. There need not be confusion in the world because of a messy scrawl! The Palmer Method of Business Writing sold one million copies in 1912. By 1927, the year that Palmer died, 27 million Americans had learned the Palmer Method.

Source: Mike Sull's Spencerian Script and Ornamental Penmanship

The Palmer Method prevailed in the twentieth century throughout the American school system, not only as a way to teach penmanship, but as a method to ensure that all students would write the same. It took two generations to kill the legacy of Austin Palmer; as a result, my son's handwriting resembles nothing but his own gestural impulses. Ultimately, isn't this why we have hundreds of typefaces? Mercifully, Palmer died and went to heaven so that the richness of life and history and (hand)writing can survive.

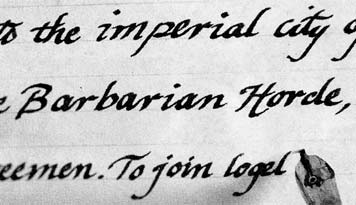

These ruminations were inspired tonight by David M. Northrup, a retired English teacher in Rochester New York, who this week won the World Handwriting Contest. As reported by The New York Times, Northrup used to have normal handwriting — in the 1960s it was basically illegible. But he bought a fountain pen and began teaching himself a handwriting script based on a Renaissance italic. He graded homework and signed mortgage documents with his distinctive script. His students began saving their homework because of his craftsmanship.

Photo: Michael J. Okoniewski for The New York Times

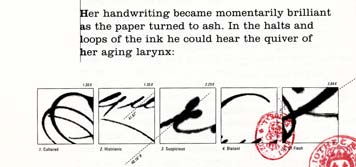

Northrup turned to a Renaissance italic for a way to write, to take a fountain pen in his hand and to craft his own voice: he graded each student paper, one at a time, with this found voice. How is this different than Stephen Farrell creating Volgare, his font inspired by an early manuscript in the Newberry Library in Chicago? "Volgare is based on the 1601 handwriting of a clerk in Florence, Italy. This clerk was performing a simple act that is one hallmark of a civilized society: every time someone died, they added the name of that person, and the day that person died, and the neighborhood that person lived in, to a list." His novel with Steve Tomasula, VAS: An Opera in Flatland, takes this voice into even richer territory.

Source: VAS: An Opera in Flatland

I'm not really concerned whether my son, Malcolm, turns to the Renaissance for his inspiration. I'll leave that to him. I just hope he finds his own voice, his own way of writing with language. This will make him a designer in my eyes, forever.

[Should you wish to enter the World Handwriting Contest next year, please visit their website. Music composed by Thomas Campion.]

Comments [19]

I know that my handwriting and that of my coworkers is a blashphemy to the written word. I am always amazed when I run across someone who writes like they just got out of second grade; their flourishes fresh in mind and on paper.

It is interesting how the quality of one's script used to be some measure of the writer. Now with the typed word and quick messages, that measure is simply the ability to use proper grammar and punctuation.

Thank you for the brief history of handwriting.

07.27.04

11:02

It is interesting that little kids give hints at what they are going to do in the future with something so simple as writing in a journal.

07.27.04

01:21

Besides, it would wreak havoc at the office. Imagine if all the little post its and jottings at everyones desk were written in the same hand. You wouldn't know who wrote what. Did you write this number down last week? Or did Bill in accounting write it yesterday? Chaos ensues.

A fellow designer, and friend of mine, traveled the world asking people to write the alphabet in a sketchbook he carried. He has since filled 5 books, and counting. Paging through them one can't help but notice the variations, subtle and glaring, from one hand to another. The feminine hand, the Asian hand, the angry hand. It's all very interesting.

07.27.04

01:48

If there was even the most remote possibility that people would all have the same handwriting, then how could there be a competition such as the World Handwriting Contest? If it were possible, the top tier of hand writers would all be equal, since they aspire to a common goal (as the students of the Palmer Method would).

I don't know anything about the interpretations of graphology, but will admit to passing certain judgment upon seeing an adult's handwriting. I too like the subtleties of different handwritings, but don't believe that it is an excuse to accept illegible or ugly handwriting - unless that fits the personality somehow.

It's interesting that we are generally taught handwriting once, at an early age. Our personalities are certainly expected to change with years, why shouldn't we be encouraged to modify our writing styles along the way as well?.. that is, if we do believe that handwriting _somehow_ represents our personalities.

07.27.04

03:49

You're Kidding us Right. Malcolm, is pre-destined to be a Designer.

He's already acclimated in using white space successfully.

The scratch-out is a la Bob Gill's Famous Design for Private Secretary. Starring Ann Southern.

I'm not a Graphologist. His strokes are solid and secure. Certainly, his bold exclamation point. Reveals his inclination toward Graphic Ideation.

When I was in the sixth grade. Eleven years old.

I always joined my name together. Without breaking the stroke. When writing cursive.

I'm still doing the same thing at forty eight (48).

When I became a Designer many years ago. I learned BASS, RAND, Chermayeff and Glaser did the same.

How's that for Graphology.

Mathmaticians can become Designers. Look at John Maeda.

07.27.04

05:55

07.27.04

06:42

But I find the idea of using graphology to determine an individual's character more troublesome than the idea of universalized handwriting. Interestingly enough, MSN very recently had a news item about graphology and business hiring practice (it was one of those links you idly click on and read after signing out of hotmail, so, unfortunately, there is no link) in which human resources types sent prospective employees' application forms to graphologists in order to get a better sense of the applicant. Surprisingly, a number of businesses use this screening test, which I liken to using Ouija boards or East Village fortune-tellers. I hardly find it a science. An interesting endeavor, like astrology or numerology, but something that, in my opinion, doesn't have a place in civic society. If I were judged on my handwriting skills, I'd never get a job, and would probably be institutionalized.

Regarding universalized handwriting, it's interesting to note the time in which Palmer existed. At the turn of the century, the US found itself with a huge immigrant population (percentage-wise, larger than now), and there was a strong drive towards Americanization, with thepublic school system being the main tool in homogenizing Hyphenated-Americans. Now, of course the story is different, multiculturalism and difference is ideologically favored over homogenization.

On the other hand, I do think graphologists can come in handy when verifying authenticity of autographs. Or, at least, it makes a good novel, anyway...

07.27.04

08:12

If body language and intonation affect our interpretation of words, why wouldn't handwriting? Typography too reflects the personality of what is written - except it is not often used for anything truly personal, the way that handwriting is.

I don't believe, myself, that graphology is near as good an indicator of personality that mannerisms or speech are, but evidence of character in handwriting hardly seems mystical.

07.28.04

09:59

07.28.04

01:35

Having been schooled in the US with that attitude that we each had to write exactly the same way, I at an early age, decided that that was fine but my signature, MY signature, would become my own and not follow any logical system. I practiced varying styles and adjustment to the school learned script, stole the typographic smiley face from the bowl of my late-grandfather's script capital I, and I was well on my way to being, in my own mind, independent of the rules.

It's funny the things we do as kids to mark the world, or at least our own work, as really being just ours. And whether or not graphology can really discover our 'special' traits is best left to the pseudo-mystics and snakeoil salesman of our world.

07.28.04

02:08

For what it's worth, the name Palmer sounds very familiar. Did his techniques persist in altered form? Did an educational company take his name?

I think that there are advantages and disadvantages to a bit of penmanship. Clearly, there's a certain utility in teaching children which letters are which, and how to form them efficiently. With that in mind, though, being concerned with the precise formation of these appearances might not be practical, both because of variances in individual ability and because fostering creativity in education is a noble goal.

I look at my handwriting today (at the advanced age of 24) and it's nothing at all like what we learned in elementary school. If anything, I feel my handwriting is still developing. I went through a heavy printing phase (all caps, but some were larger than others in proper names, etc.) and a full-on scrawl phase. My letters blend together in sort of a perverse half-cursive these days.

Sometimes it depends on what I'm doing, or if I'm writing to myself or others. Occasionally, I'm tempted to give up writing things down altogether and just write straight lines in my notebook...

07.28.04

02:44

Too bad no designer's researched the process of handwriting acquisition. I'm convinced it heralds the replacement of early childhood right-lobed "visual thinking" with literal oppressive-conforming left-lobed rigidty. So do we make good social minions of our children.

07.28.04

03:20

I see this conversation as very related to the arguments in bilingual education, which attempts to preserve the home language of the child in public life, as well as the argument for the recognition of ebonics as an official language, in order to officially sanction the ways of speaking of an historically oppressed minority. It's a way of not eradicating what is special and unique amongst us as a multicultural society. On the other hand, as someone mentioned before, we are judged by how we speak. Though it is basically illegal in the US to judge someone based on national origin and skin color, stereotyping and profiling through accents continues to be, more or less, an acceptable form of classifying people. Witness the continued stereotyping in the media of Southern accents, and, to a lesser degree, "Gangsta Speak", South Asian accents, and East Asian accents.

If anything, too much difference to the norm shown through handwriting would be a bad thing, if we were to be judged by our handwriting skills. Outside of art-related industries and the medical fields, neat and legible handwriting would be interpreted as an ability to take orders and conform, something which most positions in the job market require.

Typography, after all, is the mechanical regularization of handscript. As someone mentioned before, we probably keyboard much more than we handwrite. Is individuality, as found in the gestural stroke in handwriting, a great loss? If it were not for universalization of letterforms through type, we wouldnt have the sort of conversations like this that the Internet, and bitmap, digital type, makes possible.

As far as signatures go, I learned mine by imitating my father's unique chicken scratch in order to cut classes in high school. An attempt at authenticity and authority, through fakery and imitation, has now become part of me.

07.28.04

03:52

I worried at his self-designed flourishes - the scrolls and extra loops he routinely inserted - thinking they were evidence of his inability to copy and indicators of poor performance in class. Now, however, I see it differently. I think the onset of penmanship instruction is one of the first steps in the process of disengaging ourselves from right-brained thinking.

I already miss the nights he sat on my lap for a book reading; I miss some of the baby talk he once used; now I will find myself missing the idiosyncratic ways he found to differentiate and identify himself.

Boo uniformity! Interesting that we now have numerous fonts designed to look like individual handwriting. There is such a desire in this society to celebrate the individual - by mass producing it.

07.29.04

03:01

08.02.04

08:02

08.17.04

04:57

Inform me (by e-mail) when the next handwriting

competion in California is scheduled.

thank you 10/6/04 - 3:10 pm

10.06.04

06:04

02.18.05

10:47

The point being, there is a huge difference between writing for pure communicative purposes, and writing for more aesthetic reasons. As someone who's boss has despicable writing, I can say that sometimes too much "individuality", at least in a business setting, can be a very bad thing. If writing for purely comunicative reasons ceases to be legible, what is the purpose?

To push the point with a music analogy, really great jazz improvisors have to know the "rules" at an almost unconscious level to know how, when and where to push or break with conformity to make the best statement. Miles wouldn't be Miles if he was unaware of what he was doing.

02.23.05

01:10