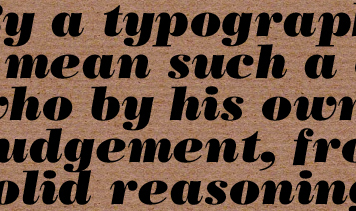

From Joseph Moxon's Mechanick Exercises or the Whole Art of Printing, 1683-4. Letterpress broadside on paper towel, 1980.

When I was an undergraduate student and stumbled onto a course called Introduction to Graphic Design, one of my first assignments was to typeset — yes, with cold metal type — a quote by Joseph Moxon. As a typographic rookie, my understanding about the principles (let alone the nuances) of designing with letterforms was negligible, as were my research skills. Better investigative strategies might have led me to discover that Moxon was a seventeenth-century printer whose puritanical upbringing was reflected in a kind of zealous precision with regard to everything he touched.

Clearly, I didn't get the memo. So while my classmates produced elegant specimen sheets with evenly-spaced letterforms, I went into the bathroom, grabbed a few feet off the paper towel roll, and printed a long, scroll-like thing in 48-point Poster Bodoni Italic.

I was told I had no future as a designer. Today, my efforts would have been applauded.

Some years later as a graduate student in the same school, our first exercise setting type digitally required us to do the same thing on a composing stick: we made four book covers on a Vandercook, then with Moxonesque fastidiousness, duplicated our efforts in what I can only imagine was Quark 1.0. By then, my understanding of typography had perhaps matured, however marginally, and I used regular paper. But the prophecy stayed with me, its residual messsage boiled down to this: if you can't follow the brief, if you can't be responsible, if you can't follow the rules, you have no right being a designer.

Today, nothing could be further from the truth. And while the fundamental principles still apply, who would dare to suggest, in a classroom or elsewhere, that there are even any rules to follow? In the age of ubitquitous computing, the exigencies of computational rigor bring their own rules: code it wrong and it doesn't work. Tag it improperly and nobody can find it. But that's only part of it: the real shift is that following the rules only takes you so far. Even Paul Rand, that most orthodox of principled designers, knew this: "You must first know the rules," he once said, "and then break them in an intelligent way."

But who is to say what's intelligent — or not — about rule-breaking? When I was a student, the assignments and their expected outcomes were intentionally conceived as chore-like, specific and frankly, narrow. This was the age of zero tolerance: deviation from a designated format was neither an approved approach nor an acceptable method. (Today, the opposite is more likely to be true: a student who does not expand his or her approach to a project is strongly encouraged to do so.) Odd, in a way, that the lion's share of my faculty then — a generation who came of age in a climate of wartime resistance and later, post-war optimism — should have been so resistant to what might have been much more experimental shifts in expression. (When Oskar Schlemmer made those goofy costumes for his Triadic Ballet, was he hailed as a visionary or reprimanded for disrespecting geometric purity?)

This strikes me as a chapter in the social and cultural history of this profession that has yet to be examined. There was, twenty years or so ago, a certain amount of consensus around the notion that imposed limitations bred a certain amount of freedom. Good work emerged when the tension between structure and freedom was clear: this was, after all, one of the fundamental goals of the page-grid, an armature or foundation upon or within which the content — of, say, a book or a poster — could be safely placed. Similarly, such a predisposition was in many cases a kind of essential component in curriculum-building: the rule-based brief was intended to promote an awareness and understanding of principles: color, balance, harmony, composition, hierarchy, symmetry, etc.

What a bore. Today, you can go pretty much anywhere online and get a crash-course in things like the "rule of threes" — the fast food equivalent of a design degree. More committed design students pursue a different path, matriculating in programs across the world in which design is examined in a much broader, more inter-disciplinary context. Making form is no longer framed by the kinds of principles that characterized my own education, and it's a good thing, too. The world has changed a lot since Ronald Reagan was in office. What a relief to know that design has changed a little, too.

Comments [41]

We can at some level relate to your education experience.

Around 1996 I walked into a design class sketch session with sketches. Everyone else had digital print outs and neatly composed photoshop images. My sketches showed the grid overlaid by tissue paper showing type placement (rule line) and xeroxed images. I also had a few columns of type studies for possible treatment and a lot of resource material. I was ridiculed by many of my fellow students.

To everyone's surprise the professor commended me for not allowing the limitations of technology dictate my explorations. When he asked me to share with the class why I choose to present the work in such rough matter I told the class; "This is a sketch critic, right? So I am bringing sketches." I also pointed out the ease in which I can change layouts and maintain the grid present at all times. Until this day I bring sketches to first presentations.

I find that technology can't move to the speed of my thoughts.

12.15.06

10:18

I meant fellow classmates.

Later on I became the professor's aid an often conducted critics of other classmates work. Not a popular spot to be in.

12.15.06

10:26

I think you meant to say 'critique'.

12.15.06

01:44

Yes, critique.

Enjoy the holidays!

12.15.06

02:01

Sure, be original, but ultimately, the *paying* customer has problems that you're hired to solve with design, and some of those problems do require relatively orthodox solutions and originality gets in the way of clarity or expediency.

I've interviewed quite a few design graduates lately, from name-brand schools, and found them well versed in illustration and Flash, but barely cognizant of CSS/XHTML and typesetting, much less proper information design (charts? graphs? tables? how square, maaaan.)

It's like they aren't taught the basic process of asking questions...what is this? who is it for? what is the best way to present this information? (and, to be crass, who's paying for it?)

The schools don't help by indulging self-expression above all else; they should be rewarding creative solutions to customer problems.

12.15.06

02:04

These include obvious (to me, at least) things like "If two things look almost the same, make them exactly the same," and more idiosyncratic things like "The dimension of the gutter separating adjacent columns of type should never be more than the margin surrounding those columns."

These "rules" seem self-evident to me, but when I dictate them (usually as a corrective) to new designers of my team, I find I'm often greeted with blank stares. I've come to realize that what I consider rules are actually something closer to habits, or compulsions, or even graphic tics. I now humbly revert to saying, "I don't know why, just do it this way, okay?"

12.15.06

02:27

12.15.06

02:36

As far as interviewing recent design grads, I would gladly trade in ALL knowledge of FLASH, CSS, HTML, etc... for a basic working knowledge of design history and the rules of classical typography.

12.15.06

02:38

In fact, these are the same reaction and two choices to a single state, things looking almost the same. Glass half-empty or half-full?

12.15.06

03:15

12.15.06

04:00

- I say to my students: "If two things are similar, make them similar or make them different or eliminate one of them or add more of them."

- aj, you are painting with too wide a brush. Not all design programs are alike! Please be more specific in complaining about design education. 2 year? BA? BFA? MFA? where? who? when? and were you a A, B, C, or D student? and was it a graphic design program that admited with a portfolio or not? If BA or BFA, did your studies last 2 years or 3 in graphic design? Did you go to a comunity college and tranfer in as a Junior or did you enter as a freshman or did you study economics and switch to design at a more mature age? Did you attend a local private for profit academy or an accredited art and design program at a private or public university or college? Did you study design because your parents told you to (since designers can make a living) or did you really dream of painting all day in Typography class?

12.15.06

04:20

Technology can move at the speed of one's thoughts. It's just a matter of pushing the right buttons in the right places. As someone who -- succesfully I like to think -- sketches vigourously directly on the computer I have always believed that doodling, cutting, pasting, throwing, breaking and, even, writing straight on Adobe Illustrator is as effective as a good napkin doodle. Technology is only limiting if you let it wag you.

12.15.06

06:31

Before this becomes a discussion about "the Rules," I would like to make the claim that rules are used as a substitute for skills of observation. And because observation is a skill that one can improve and refine on one's own, rules are superfluous. The best advice one can give a student is to go look at design/typography. Spend time with books. (I have a feeling that Michael, Jessica and William have extensive libraries.)

Teaching is often a matter of teaching students "how to see" as much as it is a matter of teaching them how to think. From there, anything is possible.

12.15.06

06:40

To me, design (and more specifically, typography) is like Jazz. To the uninitiated, Jazz can just sound like a lot of notes jumbled together. And many youngsters may think they can just noodle away on a keyboard and it sounds like Jazz. But it ain't. From what I know good Jazz musicians are among the most respected in the music industry, cuz they really know their shit, and many are classically trained. I tell my students that I'm going to teach them first how to listen (metaphorically), then how to play some notes, then we're going to practice some scales, play some simple tunes, then learn how to mix the tunes up a bit ... etc. We never get to Jazz in my class; I teach introductory typography—we don't get much past "Mary Had a Little Lamb". But I do teach them rules ... a lot of rules. And you should see their faces when things start to come together for them, and they start to understand the structure and how to make something that they never could have made before because they didn't even know what they were looking at. It's a fucking miracle.

I honestly can't imagine teaching anything without rules. I just seems senseless to me.

12.15.06

09:32

My introduction to art/design was graffiti in New York City in the late 70s early 80s. I never knew there were rules until someone pointed them out to me in art school. The only rule I knew was "Never get caught by the cops on a rooftop or train hit." I've been sketching on paper for over 20 years. The reason why I've never embraced sketching on the computer... too many lines to chase.

I am honorary member of one of NYC's most influential graf crews. Check us out on the book:

Broken Windows: Graffiti NYC

Book review

Buy the book

12.15.06

10:18

12.15.06

10:48

He replied; "You will know it when you hear it."

12.15.06

10:55

"The rules" - however defined - provide a point of reference that no lack of rules could ever provide. This is true whether you worship the rules or turn them on their head.

12.15.06

10:59

For example, I prefer to give students readings from Geoffrey Dowding's "Finer points in the spacing and arrangement of type" rather than Jan Tschichold's "The form of the book" because Dowding contextualizes why typographic form has evolved along the lines it has. Tschichold is more dogmatic about his typographic preferences, while Dowding provides the reader with greater information about how typographic conventions have developed. In so doing, Dowding gives the designer greater options for understanding when s/he is breaking with convention, when it is appropriate to break with convention, and what effect that break might have on the intended design.

The blind application of (arbitrary) rules absolves the designer from having to think about the context and effectiveness of their design choices. Of course students need to learn the basics of design, but they don't need to learn according to a series of absolutes.

12.16.06

12:24

What is the criteria of success for design?

To be original?

To make beautiful objects & get paid to do it?

To serve the client?

To communicate information in the best way possible?

To mediate commerce and art

To interlope commerce to make society better?

All of these? None?

These all seem lacking in anything measurable. Can you really measure beauty, originality, clarity?

That is why "rules" dealing with design are hogwash. As long as our goal in this profession isn't measurable, the rules attached that goal are going to be as arbitrary as shit.

Compare our profession's "goals" with any other areas of study and you'll see what i mean:

Sociology's goal is to understand how and why societies works.

Biology's goal is to understand how and why life works.

etc., etc.

you don't break the rules of research methodology for your field—because you're not helping in achieving your goal of understanding if you do so.

Make it New is so Modernist, and I thought we destroyed that ideal decades ago. How is this our criteria for success?

Make it beautiful is just an excuse to runway from the reality of Power, Politics and Economics, and instead just decorate chicken shit and repackage it as chicken soup.

Make the client happy doesn't define anything, and who ever said the client knows what's the define criteria for success is for design?

Make information as clear as possible this doesn't take that much. A sexy poster and a lame Microsoft word comic sans poster will both say: Name of band, place of show, time of show, cost of show.

Why do we designers for this again? This made sense when designers had a commodity on the means of production for communication. That's far from the case today, as everyone knows.

Mediate commerce and art First tell me what the hell "art" is, then we can talk.

My point is that if we really want to talk about "rules" we need to attach those rules to what the goal is. And i don't think graphic design has a goal that's measurable or objective in any matter. And as a result the "rules" graphic design are invalid.

12.16.06

12:36

If anyone wants to know what "the rules" of classical typesetting are, Robert Bringhurst's The Elements of Typographic Style pretty much nails it; that and Making and Breaking the Grid by Timothy Samara are two excellent collections of fundamentals that work well together. After that I'd say Tufte's Envisioning Information, if you had to pick just one of his works.

As to what the goals of design, the profession are, Mr. Jockin doesn't clarify but he does point out a lot of what obfuscates the issue. I think far too many people confuse design with styling, decoration, and capital-a Art. Design can be part of art and vice versa but to make a useful distinction, art is pure expression and design clarifies intention.

You will go to a gallery and see a piano suspended from the ceiling that apparently self-destructs every few minutes, and it's wonderful art; however, an Ikea bread knife designed like a hacksaw - clever innovation, simply executed, and intuitive to use - is wonderful design.

12.16.06

01:52

If a design does not make the message clear. If it confuses, frustrates, interupts, or gets in the way of enjoyment and understanding; it fails.

Rules are the secret sauce a good designer uses to impress their friends and confound their enemies.

Rules are contextual. The rules of design change dramatically when delivering content to a mobile phone, ipod, web site, or a 16 year old. A good designer knows her medium.

The rules are broken, rewritten, and re-engineered as the medium and culture demands. A good designer is immersed their medium and culture. A good designer embraces change.

Rules are the shorthand you learn so you get the job done effectively, on time, on budget. If you know the rules you can learn from other peoples work instead of stealing it. Rules let you sleep at night.

A good designer knows the rules.

12.16.06

03:03

Now, as a teacher of these skills, these fundamentals, I draw upon my own experience in making things and offer these conventions to my students. I empathise with Mr. Bierut's experience with "self-evidence" in the function of elements on a page. When left to their own devices, students inevitably center half of their text, then throw a little out of the margins and align it with the tab key, or by eye. Eek!

Only over a strong and strict foundation of rules can one build or break their work. Picasso's "Demoiselles d'Avignon" would have fallen flat without his blue period. Imagine how much sense "Broadway Boogie Woogie" would make without Mondrian's ascension from semi-abstraction into pure abstraction. Donald Judd would have had nowhere to hang his hat.

Breaking the rules in adolescence is often a very raw but sloppily approached adventure. Breaking them after maturity is a conscientious choice.

Imagine the road less travelled as the road everyone is travelling. Where, then, all the difference?

12.16.06

04:25

"I've observed something about the modern world, and that is that it encourages creativity and uniqueness in people than ever before. This is very bad. I learned in school that it was more important to be 'unique and creative' than it was to be smart or knowledgeable. Dumb people on MTV or in artsy fartsy magazines who aren't smart or creative tell you what smart and creative stuff to like. I wasn't around until a somewhat short while ago, but I believe in the past people who were meant to be artists simply became them because there wasn't anything else to be. Today there are millions of 'creatives' fighting to be the most popular with our dumb modern culture." - Katie Rice

12.16.06

02:58

i ask because i've never seen letterforms printed in letterpress crash that much, and it looks impossible to do in cold metal. i'm looking at the d and g in the last lines.

12.16.06

03:54

/RV

(.srettel eht pilf ot woh tou erugif t'ndluoC .s.p)

12.16.06

06:09

Is not Fashion design? If it is, we need to tread our trails very careful, becuase I would have to disagree with you and say we graphic designers fall into this arena very easily.

What is the purpose of fashion? It's to seperate the classes—a siginifier of the upper class verus the lower. Is that not what a lot of graphic design does? Siginify a thing of communction as "professional", "classy", "sleek", "authouriative"?

Has "art" always been about expression? Were gothic scuplutres adventures in expression, or where they illustrations of bibical narratives? To define art as pure expression is a 20th century defination. There was a time when aseathics was hand in hand with morailty and ethics( both the religious and the craftsman's). I'm of the opinon that "art" as we know it was the result of modernity— where in that process excatly I'm not sure— with the seperation of the spirtual from the religious and the form from the content.

...an Ikea bread knife designed like a hacksaw - clever innovation, simply executed, and intuitive to use - is wonderful design.

yes, if it is useful then it is good design. this appilies to all design( which is in my opinion also includes "art" as a cataergory, becuase there's only been design, "art"'s just an invention of modern rhetoric).

usefulness actually can be measured as a defined goal.

Did I learn/ become aware of something i didn't know before?

is one such example. This requires the right message, the right timing, the right medium, and the right narrative.

Josh,

Design facilitates proper use and understanding. The medium and culture dictate the rules. end of story.

If a design does not make the message clear. If it confuses, frustrates, interupts, or gets in the way of enjoyment and understanding; it fails.

I find it somewhat humous that while you state the message must be clear, you state the culture and medium dicate the "rules".

Are you admiting that every message is loaded, based on that very culture and medium that is used to present the message?

Or are you stating that the "rules" are to nulify those biased elements of culture and medium?

and most importanly, how do you know if your message is clear? Based on Swiss Typographic Laws? How is that in any way provable?

12.18.06

06:12

'and most importanly, how do you know if your message is clear? Based on Swiss Typographic Laws?'

precisely

12.18.06

08:49

ah, that explains the sameness I see everywhere I look in the States. Those guys were being paid to solve problems, not to be interesting. Good work, and keep it up. With any luck the future monoculture will be entirely without annoyances like originality, mistakes, and any kind of opinion not agreed upon in a board meeting.

yawn.

12.19.06

08:51

12.19.06

10:02

Instead what I see are vast bodies of work (my own included) defined entirely by templates, as though problem solving was linear algebra. Its especially disturbing in the field of interactive graphics (my own line of work), where designs can potentially reflect the state of a larger system and again, instead of that, what I see are the same solutions applied to new problems again and again.

Deadlines & expediency are a fact of life, so is maturity and experience, yet that can't be all there is.

12.19.06

10:21

Sometimes the problem involves clients, budgets, deadlines. Same as a painting a chapel roof in Rome.

12.20.06

08:35

Rather, art is what the art world believes is art. Unfortunately.

Kind regards, Olof, Sweden.

12.20.06

11:07

I am largely self-taught as a graphic designer so I don't do things because my teacher said to. Students do not, however, escape my design classes without proof of facility with traditional punctuation and the ability to use grids. I make what I consider a good case for the use of typefaces that they start out thinking of as boring; by the time I am done, many seem to agree with me.

So what up with this "rules" stuff? This, like so much of graphic design discussion, strikes me as a problem of misclassification. If we take what are described as "rules" and divvy them up into three piles—principles, tools, and conventions—they become (like grids and printing technology) creative and communicative opportunities rather than limitations that inspire either unswerving obedience or adolescent rebellion.

So, it is a principle that when two things are almost alike the differences become more significant than similar differences [sic] would be for two things that are otherwise more dissimilar. The question of the significance of the dissimilarity can make people uncomfortable so a designer needs to ask what purpose there is to this discomfort. It can look unintentional and sloppy so the designer needs to ask what result will come from an impression of imprecision. Most of the time one would end up choosing to make the things more alike or less alike but in some cases the discomfort or questions regarding craft might be used to good end. In general, ambiguity of various sorts can be useful and can enrich communication; for the most part it is not and does not. (BTW, the same applies to things that are depicted as nearly life size. Consideration will, in most cases, lead one to make the image precisely life size or nowhere near life size. The two similar things do not have to be on the same page for this principle to apply.)

So Michael's "rule" is not a rule. It is a "rule of thumb." It is a shorthand for more complex information. If it is stated as a law to be followed rather than as a principle to be understood then it interferes with learning to be a graphic designer rather than advancing that goal because rules (in the legal sense of the term) make an activity that could be rich and complex into something mechanical.

12.24.06

12:05

UGHHH!.. the rules, the attention to such detail, I thought to myself, does anybody really give a f*** about this stuff?

The assignments were so rigid, and we had to pay attention to detail and follow the rules for the assignments so closely. I as afraid of my nazi-typography teacher!

Interestingly enough those that got the best grades, broke the rules.

Rishi

http://gumpdesign.blogspot.com

12.25.06

09:56

Anything at my school, Parsons, that flies, is anything that breaks the pre-defined rules, yet pays respect to them. There is a fine line between pissing off the creator of the system, and pleasing them with an ingenious introspection.

Consider it.

12.25.06

10:19

So stop worrying about being submissive or transgressive and about pissing off or pleasing. Worry about what the (supposed) rules mean or do then do good work based on all you know. If your teachers give you rules, ask about and try to understand the reasons behind the rules. BTW, a seemingly-rigid assignment is often about forcing the attention to detail that gets lost for people who are struggling with all that ingenuity and expression.

12.26.06

10:30

02.01.07

07:21

02.01.07

07:22

02.01.07

07:39

It is possible to come up with decent ideas by following a set criteria but only by thinking outside of the box can award winning ideas be achieved. Creative thinking and unique ideation are a goal, not a five step process with an emphasis on guidelines and order.

However, some rules are needed to help rid students who have been brainwashed by a bombardment of media everyday. Technology is getting better and should be utilized but designers should not jump immediately to the computer and hash something out. Sketches, thumbnails and any other type of rough layouts are important for design and should never be overlooked.

Thanks.

03.20.07

08:07