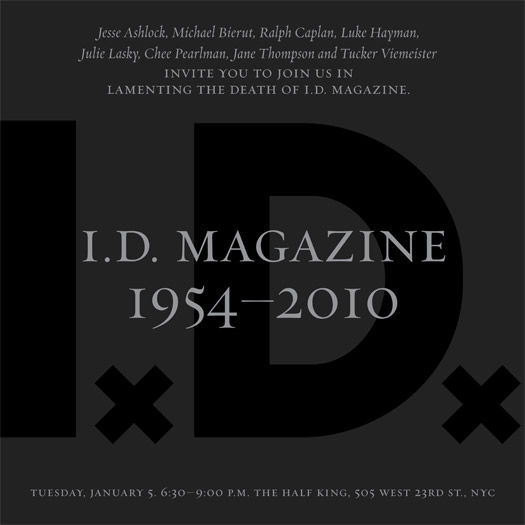

Invitation to I.D.'s wake, January 5, 2010. Designer: Luke Hayman; typeface: Requiem by Jonathan Hoefler.

Late in 2002, a publisher asked me to consider editing a beloved design magazine that had fallen on hard times. Three years before, the magazine had been relocated from New York, where it resided for decades, to its parent company’s home in Cincinnati. The decision proved disastrous. Supervised by eager yet inexperienced editors removed from the metropolitan swim of design — the unceasing flow of product introductions, PR lunches, trade shows, hard-hat building tours and studio visits — the magazine had lost its focus and much of its audience and was consequently hemorrhaging readers and ad dollars.

“So, will you think about taking over I.D.?” the publisher asked.

“Absolutely not,” I said.

I knew all about this bungled Ohioan adventure from a previous I.D. editor, who happened to be a friend of mine. He had recounted being hired on the eve of the magazine’s move, though no one had told him about it. Instead, his first day on the job was spent wandering around empty offices. (Much of the staff had been dismissed the previous day, and he joked that their leave-taking was so abrupt the place was littered with half-eaten sandwiches.) As I.D.’s sole editor in New York working alongside the ad salespeople, my friend spent the next year trying to manage staff in another state whom, he complained, he had not been allowed to hire and who had never heard of Philip Johnson. He phoned me with regular bulletins of management atrocities, culminating in the rerouting of his mail to the Cincinnati office; he was actually barred from opening it. At the year’s end, my friend’s contract expired, and he left.

“No way,” I reiterated.

Besides, I was still smarting from my own recent experience of corporate brutality. In June 2001, the legendary magazine Interiors shut down because its parent company had acquired an interior design periodical that ran on a fraction of its budget. Interiors had been founded in 1888. I was its last editor. I took a chunk of my risible severance package and bought a David Wojnarowicz photograph of buffalo being driven off a cliff. Less than three months later, the World Trade Towers were blown up. I decided maybe I should hunker down in my Brooklyn apartment for a while and spent the next 18 months in my pajamas.

“Really, thanks,” I told I.D.’s publisher. “But I don’t think I can work for those people.”

“But the people have all changed,” the publisher, who was himself a new arrival, said. “The company is sorry about the mess that was made, and everyone responsible for that bad decision is gone now.”

A bottom-line-oriented company in the age of Bush had acknowledged wrongdoing and expressed regret? I looked into the sympathetic eyes of this kind man and thought about my COBRA benefits, which would soon be coming to an end. I took the job. “Don’t do what I did,” my friend the former editor said when he heard the news. “Don’t call your bosses liars. Especially not to their faces.” Six months later, the nice publisher who hired me was sent packing.

I stayed at I.D. for the next six years. Over that time, the parent company, which had been owned by a private equity firm based in Providence, Rhode Island, was sold to a private equity firm based in Boston. The new backers introduced a new CEO (an art-loving guy who had written his undergraduate thesis on the symbolism of bread in the work of James Joyce) and replaced him a year later with someone they judged more effective at cutting costs (a sports-loving guy who used a lot of basketball metaphors). For the next six years, I reported to a succession of nine supervisors, including recent publishers of magazines about horticulture and scuba diving. The blogosphere was born and the global economy fell to pieces. And yet nothing in the corporate zeitgeist shifted an iota. Though the cells were constantly regenerated, the parent entity remained exactly the same. Like hundreds of American businesses, it was obsessed with short-term profitability, the future be damned. And no one who had any serious power over I.D. seemed to understand anything about design.

On the contrary, the thread connecting almost all of the disparate players I reported to was their insistence that they couldn’t tell the difference between I.D. and its sister magazines Print and How. As the revolving door turned, I would march into executive offices carrying armloads of back issues and tell each new boss the story of I.D., from its origins in 1954 as Industrial Design to the present day. I explained that the “I” in I.D. stood for “international” but also, tacitly, “interdisciplinary” and “innovative.” I discoursed on the recent convergence of design practices that in my view made it appropriate to bundle products, buildings and graphics within the covers of a single magazine. I suggested that although I.D.’s audience was divided among different kinds of designers, which reduced its appeal to advertisers, all of those readers were visually acute and shared an interest in smart ideas. Perhaps there was a way to think about innovation as an advertising category? I showed evidence of I.D.’s global stature and urged the establishment of a strong web presence that could serve as a window on the world and open new avenues for profit (not to mention shore up I.D.’s reputation for featuring cutting-edge design). On each occasion, I was politely told that the typical buyer of advertising space lacked the time and intelligence to grasp complicated ideas such as I had just presented. Nor in six years was any notable investment made in a dedicated sales staff, reader research or web development for I.D.

Imagine going to a hospital and learning from the person holding the scalpel that he really doesn’t see a difference between your hand and your foot; after all, an appendage is an appendage, and a sock can be pulled over any of them. A blogger commenting on Bruce Nussbaum’s post about I.D.’s death wondered whether design thinking had been applied in any attempt to keep the magazine going. Don’t make me laugh. Whereas designers spend their days making astute decisions based on the accumulation of facts, I.D.’s executioners seemed to feel that genuine understanding of their property was too expensive to acquire and finally irrelevant.

In their minds, the suits did away with an antiquated pile of paper that taxed their resources and imaginations. But for those of us who produced and consumed I.D., in same cases for decades, an animate thing was prematurely struck down. Magazines are organic. They take on shapes and personalities that are independent of those who make them, and in this margin of self-sufficiency is something eerily close to life. Magazines are mammalian: warm-blooded, twitchy and dynamic whereas the businesses that buy them to turn a quick profit are cold-blooded reptiles, apt to engage in long bouts of inertia except for an occasional spastic flick of a murderous tongue.

And of course magazines are historical. The internet is a bottomless archive, but it spits information back to us in fragments, and we’re never sure which pieces might disappear forever. A magazine archive unspools to allow us to see aesthetic movements wildly imitated before they’re just as passionately revoked and to watch the youth of our industries mature and grow old and give way to new talents. Would anyone be able to make sense of so unruly a profession as design, with its vague and shifting borders, if it weren’t bound into our journals?

History is hardly respected by a company whose institutional memory is as long as my thumb. Shortly before I left I.D. in early 2009 to work on Design Observer, someone raised the idea of cutting costs by moving the magazine to….Cincinnati. So many corporate employees had turned over in six years that only a few people realized that the gambit had ever been attempted. It was then that I knew I had to go.

Late in 2002, a publisher asked me to consider editing a beloved design magazine that had fallen on hard times. Three years before, the magazine had been relocated from New York, where it resided for decades, to its parent company’s home in Cincinnati. The decision proved disastrous. Supervised by eager yet inexperienced editors removed from the metropolitan swim of design — the unceasing flow of product introductions, PR lunches, trade shows, hard-hat building tours and studio visits — the magazine had lost its focus and much of its audience and was consequently hemorrhaging readers and ad dollars.

“So, will you think about taking over I.D.?” the publisher asked.

“Absolutely not,” I said.

I knew all about this bungled Ohioan adventure from a previous I.D. editor, who happened to be a friend of mine. He had recounted being hired on the eve of the magazine’s move, though no one had told him about it. Instead, his first day on the job was spent wandering around empty offices. (Much of the staff had been dismissed the previous day, and he joked that their leave-taking was so abrupt the place was littered with half-eaten sandwiches.) As I.D.’s sole editor in New York working alongside the ad salespeople, my friend spent the next year trying to manage staff in another state whom, he complained, he had not been allowed to hire and who had never heard of Philip Johnson. He phoned me with regular bulletins of management atrocities, culminating in the rerouting of his mail to the Cincinnati office; he was actually barred from opening it. At the year’s end, my friend’s contract expired, and he left.

“No way,” I reiterated.

Besides, I was still smarting from my own recent experience of corporate brutality. In June 2001, the legendary magazine Interiors shut down because its parent company had acquired an interior design periodical that ran on a fraction of its budget. Interiors had been founded in 1888. I was its last editor. I took a chunk of my risible severance package and bought a David Wojnarowicz photograph of buffalo being driven off a cliff. Less than three months later, the World Trade Towers were blown up. I decided maybe I should hunker down in my Brooklyn apartment for a while and spent the next 18 months in my pajamas.

“Really, thanks,” I told I.D.’s publisher. “But I don’t think I can work for those people.”

“But the people have all changed,” the publisher, who was himself a new arrival, said. “The company is sorry about the mess that was made, and everyone responsible for that bad decision is gone now.”

A bottom-line-oriented company in the age of Bush had acknowledged wrongdoing and expressed regret? I looked into the sympathetic eyes of this kind man and thought about my COBRA benefits, which would soon be coming to an end. I took the job. “Don’t do what I did,” my friend the former editor said when he heard the news. “Don’t call your bosses liars. Especially not to their faces.” Six months later, the nice publisher who hired me was sent packing.

I stayed at I.D. for the next six years. Over that time, the parent company, which had been owned by a private equity firm based in Providence, Rhode Island, was sold to a private equity firm based in Boston. The new backers introduced a new CEO (an art-loving guy who had written his undergraduate thesis on the symbolism of bread in the work of James Joyce) and replaced him a year later with someone they judged more effective at cutting costs (a sports-loving guy who used a lot of basketball metaphors). For the next six years, I reported to a succession of nine supervisors, including recent publishers of magazines about horticulture and scuba diving. The blogosphere was born and the global economy fell to pieces. And yet nothing in the corporate zeitgeist shifted an iota. Though the cells were constantly regenerated, the parent entity remained exactly the same. Like hundreds of American businesses, it was obsessed with short-term profitability, the future be damned. And no one who had any serious power over I.D. seemed to understand anything about design.

On the contrary, the thread connecting almost all of the disparate players I reported to was their insistence that they couldn’t tell the difference between I.D. and its sister magazines Print and How. As the revolving door turned, I would march into executive offices carrying armloads of back issues and tell each new boss the story of I.D., from its origins in 1954 as Industrial Design to the present day. I explained that the “I” in I.D. stood for “international” but also, tacitly, “interdisciplinary” and “innovative.” I discoursed on the recent convergence of design practices that in my view made it appropriate to bundle products, buildings and graphics within the covers of a single magazine. I suggested that although I.D.’s audience was divided among different kinds of designers, which reduced its appeal to advertisers, all of those readers were visually acute and shared an interest in smart ideas. Perhaps there was a way to think about innovation as an advertising category? I showed evidence of I.D.’s global stature and urged the establishment of a strong web presence that could serve as a window on the world and open new avenues for profit (not to mention shore up I.D.’s reputation for featuring cutting-edge design). On each occasion, I was politely told that the typical buyer of advertising space lacked the time and intelligence to grasp complicated ideas such as I had just presented. Nor in six years was any notable investment made in a dedicated sales staff, reader research or web development for I.D.

Imagine going to a hospital and learning from the person holding the scalpel that he really doesn’t see a difference between your hand and your foot; after all, an appendage is an appendage, and a sock can be pulled over any of them. A blogger commenting on Bruce Nussbaum’s post about I.D.’s death wondered whether design thinking had been applied in any attempt to keep the magazine going. Don’t make me laugh. Whereas designers spend their days making astute decisions based on the accumulation of facts, I.D.’s executioners seemed to feel that genuine understanding of their property was too expensive to acquire and finally irrelevant.

In their minds, the suits did away with an antiquated pile of paper that taxed their resources and imaginations. But for those of us who produced and consumed I.D., in same cases for decades, an animate thing was prematurely struck down. Magazines are organic. They take on shapes and personalities that are independent of those who make them, and in this margin of self-sufficiency is something eerily close to life. Magazines are mammalian: warm-blooded, twitchy and dynamic whereas the businesses that buy them to turn a quick profit are cold-blooded reptiles, apt to engage in long bouts of inertia except for an occasional spastic flick of a murderous tongue.

And of course magazines are historical. The internet is a bottomless archive, but it spits information back to us in fragments, and we’re never sure which pieces might disappear forever. A magazine archive unspools to allow us to see aesthetic movements wildly imitated before they’re just as passionately revoked and to watch the youth of our industries mature and grow old and give way to new talents. Would anyone be able to make sense of so unruly a profession as design, with its vague and shifting borders, if it weren’t bound into our journals?

History is hardly respected by a company whose institutional memory is as long as my thumb. Shortly before I left I.D. in early 2009 to work on Design Observer, someone raised the idea of cutting costs by moving the magazine to….Cincinnati. So many corporate employees had turned over in six years that only a few people realized that the gambit had ever been attempted. It was then that I knew I had to go.

Comments [29]

01.13.10

11:36

01.13.10

11:41

01.13.10

11:59

01.13.10

04:11

See the New York Times Business videos –

"Flipped: How Private Equity Dealmakers Can Win While Their Companies Lose"

Another example of the need for finance reform.

01.13.10

04:32

01.13.10

04:48

01.13.10

06:42

01.13.10

06:49

“...a sports-loving guy who used a lot of basketball metaphors”

Sad:

“In six years was any notable investment made in a dedicated sales staff, reader research or web development for I.D.”

01.13.10

07:25

While it takes a concerted effort—often by a number of determined, imaginative, and talented people—to create anything of value, its destruction can generally be accomplished quickly and easily, whether through maliciousness, ignorance, stupidity, or—occasionally—careful consideration of the trade-offs involved.

My sympathies and best wishes for the future to all of those who worked diligently to build I.D., and my thanks to Julie Lasky for sharing her story.

01.14.10

02:13

The last decade has been an easy time to make money. Some company's have forgotten

Magazines are about making a great product not huge profits.

Gradually reducing quality to make more money is not very clever.

If its not giving the reader value they won't buy.

01.14.10

07:02

With people utilizing internet access more and more for information, blogs and sites that update daily keep attention (and stay on my mind), while in comparison ID magazine only came 8 times a year...

01.14.10

09:34

OK: Then why do we have Design Observer?

Blogs and the ad crunch would quite possibly have been enough to do in a magazine whose editors always seemed to believe themselves stewards of design (people who “make sense” of it) rather than, as Lasky disingenuously claims, mere chroniclers of it (in “bound... journals”).

Design criticism: Still a T-Rex wondering what that bright light in the sky might be.

01.14.10

09:34

01.14.10

09:55

julie - you were a trooper and did your best given the circumstances. i need not tell you my own personal relationship to the entire saga, suffice it to say, i feel your travails and then some.

there was no "better" decade. ID was always great. it held the bar (of recognizing design quality) pretty damn high, so now we have to continue to live up to it even though it's gone. i think we can, but maybe harder for ramon.

g

01.14.10

01:45

The writing has been on the wall for print media (magazines, newspapers) for close to a decade. Problem is nobody bothered to look.

If ID magazine had applied "design thinking" to its own situation, it would have realized it needed to evolve to remain relevant. As a printed publication, they were simply the middle man between the content and the reader. Sites like Core77 got it and became aggregators to content as well as facilitators for people to share their own findings and content via blogs and discussion boards.

While I enjoyed ID Magazine in the pre-Internet era, I am not shedding any tears for its demise. They had ample opportunities to do something about it.

01.14.10

03:41

It's that simple. The writing was awful. Each article hyped Karim Rashid-like substanceless design. The photographs tried to mimic Rolling Stone circa 1994, with out of focus, poorly cropped material.

It was garbage for the last fifteen years.

A lot of magazines are failing because of the economy. This isn't one of them. It failed because it sucked.

01.14.10

09:00

What you describe was exactly what happened; I was one of the staff who got the axe the day before your friend started his one year stint at the magazine. It appalls me that this type of mismanagement dragged on for a decade.

ID was responsible for a new way of looking at the everyday and magazines like Wallpaper picked up on and became very successful with, because they had experienced publishers and resources behind them.

01.14.10

10:42

01.15.10

01:35

As a designer wanting more that to hunker down and do one thing I got a chance to dream of the possibilities in design in its many forms and what other thinking people with talent were problem-solving.

I for one will miss this magazine—I think that a lot of us will—not only for its exposure to new design methodologies, its great writing and images but also for the good friend we had, now gone, who gave us great insight and sound advice. So long I.D.

01.15.10

02:21

I would like to acknowledge for bravely fought, and hold the space as long as you were there. To be frank, I couldn't afford any when I was a student of a local college in Malaysia, however, it has always been my comfort zone whenever I hit the library (at least a good 3 hours per day , max 12 hours).

That comfort inspired me daily, what it is like to be creative, which what I have always wanted to be since I was 9.

Again Thanks Julie.

01.16.10

02:35

Julie, thanks for telling your story. As you know, I can relate. Meeting with the F&W people in Cincinnati after that awful, imagination-less company bought I.D. was among the most depressing periods of my life. The writing was on the wall immediately. You were brave to take on the project, though it sounds like it was a struggle all the way through.

01.16.10

09:00

01.18.10

03:08

Everyone is quick to blame the Internet, economic conditions,changing reader habits, etc. as the root cause for the demise of print publications. While all those things are contributing factors, the reality is many publications have suffered from years of neglect and mismanagement.

01.20.10

10:02

01.20.10

03:03

01.20.10

10:07

Let me share some grief with you to sooth the pain of the demise of ID magazine. Items, the Dutch design magazine I'm editor of, also came into turmoil last year after the publisher went bankrupt. Apart from pain of the unpaid bills, the existence of the magazine was in jeopardy. But we are lucky. Max Bruinsma, the editor in chief, and Pao Lien Djie, the managing editor, pay much effort in saving the magazine, and with the help of some friends and friendly foundations Items has made a restart.

The magazine wasn't the cause of the bankruptcy, but bad management of its owner, a printer and wouldbe cultural entrepreneur from a small town in the Dutch bible belt. He even had a little theater next to his printing house, where the late Willy DeVille once played. They are still talking about it there.

The ponytailed printer bought Items in 2007, because he said he loved it, though he never read an article. His biggest contribution to the magazine was an idea to sell eight or more pages to designers, they could make at will without editorial interference. That's not making a magazine, we said, but he didn't understand that. Then Items had a near editorial-office-has-to-go-to-Cincinnati experience. To cut costs the printer-publisher announced he wanted to move the editorial office from Amsterdam to the town where his printing house was. Soon he dropped that plan and made a 180 degree turn. Now he wanted to move his printing house to Amsterdam, because he wanted to be near the creative community (Willy DeVille had left his small town by then, so there was no reason for him to stay). He asked a famous designer to make sketches for his new printing house and rented a large space in Marcel Wanders' Westerhuis, because he couldn't wait to have his pied à terre in Amsterdam.

That was in February 2009. Three months later we all got a letter from the official receiver telling we probably won't get our money and Items moved to a smaller and cheaper office. The staff, the writers and the designers stayed loyal to the magazine so three issues could be made already without a publisher.

BTW: For some immediate comfort you have to visit the exhibition "Demons and Devotion: The Hours of Catherine of Cleves" at the Morgan Library & Museum in New York. That exhibition ran in my town until last month, and it was a blockbuster. It's a unique chance to see the finest illustrations from the late Middle Ages. An era without printers or publishers.

Marc Vlemmings

Nijmegen, The Netherlands

01.21.10

10:59

01.27.10

08:52

Visit My Blog Directory

07.01.10

04:19