Charles and Ray Eames: Stereo Photographs from View*Productions. Photo: Cheryl Yau

Charles and Ray Eames: Stereo Photographs from View*Productions. Photo: Cheryl YauThe Eames Office loft, scattered with molded plywood prototypes and rolls of craft paper. Click. The model of the Kwikset House furnished with two Eames storage units, upholstered chairs and dark orange carpet. Click. A table full of English muffins, strawberries, hardboiled eggs and a glass carafe of coffee set in front of a fiberglass shell chair. Click.

Peering through my clunky View-Master, I was transported into the Eames Case Study #8 House in Pacific Palisades, exactly as it was arranged when Charles and Ray Eames photographed it themselves. In my hands, I was holding 7 full-color Kodachrome images laminated onto a single circular reel. These were part of a set of photos intended for the Museum of Modern Art’s Built in USA: Post-War Architecture exhibition in 1952. Unlike any of the images I had seen before reproduced as slides or in a book, these stereo images — void of any editing or retouching — made me feel like I was actually there.

The Eames stereo photographs came to me by the way of Michael Kaplan, a Professor of Architecture at the University of Tennessee, and a veteran stereo photographer. Since childhood, Kaplan has had a fascination with the View-Master, collecting cartoon reels as well as photographs of national parks he dreamed of visiting. “People started collecting these pictures because it was a way to see exotic parts of the world that they could never afford to travel to,” recalled Kaplan, who grew up in the 1950’s, during the height of the View-Master’s popularity in the United States. At the time, View-Master models were sold at a dollar each (equivalent to $9.27 in 2011), while the reels themselves were only 35 cents, making stereoscopic viewers an affordable hobby. It was common for every child to own one. While adults watched television, children escaped into three-dimensional imaginative worlds. Like baseball cards and stamps, they satisfied the innate human desire to collect. For children like Kaplan in the 1950’s, collecting View-Master reels “was like having your own little art collection.”

By the time he went to architecture school in 1963, the popularity of taking 3D pictures had subsided considerably. Stereo cameras that previously cost over $100 (almost $900 today) were now easily available for fifteen dollars. Finally able to afford one, Kaplan bought his first stereo camera as a student, and his obsession continued throughout his career. “When I was teaching architecture here at the University of Tennessee, I used it all the time in my lectures. One of my students said, 'you know, if you ever want to do this commercially I’d be interested in going into business with you.' And I did.” So Kaplan partnered with his student Gregory Terry and founded View*Productions in 1997. They started out by making reels of their favorite subject: architecture. View*Productions successfully released View-Master reels of work by Frank Lloyd Wright, Ralph Erskine, Hans Scharoun and Frank Gehry, with most of the photography by Kaplan.

Architectural Classics and View-Master from View*Productions. Photo: ©Robert Batey Photography

Architectural Classics and View-Master from View*Productions. Photo: ©Robert Batey PhotographyView-Masters — and the Tru-Vues and stereoscopes that preceded them — were all based on the same principle: that of merging the images seen by both eyes into a third image. The concept began 2000 years ago with ancient mathematicians, philosophers and scholars including Galen, Euclid and Baptista Porta, all of whom wrote extensively on optics. By the time Charles Wheatstone invented the first stereoscope in 1838, the technology quickly spread to the masses. The first stereoscope was publicly unveiled at the Great Exhibition of 1851, where Queen Victoria and Prince Albert were presented at the Crystal Palace with a special viewer designed by Jules Duboscq. Stereographs produced from the 1850’s until World War I covered every aspect of life — including, but not limited to travel, education, current events and portraits. Documentation of key events such as the San Francisco earthquake in 1906 were most popular. To meet the demands of a growing national market, the stereograph company Underwood & Underwood had an assembly line that manufactured up to 3,000 cards a week. At the peak of its success, almost everyone had access to a stereoscope.

“What was so interesting about the View-Master and the other formats that came before it, was that it appealed to every age group” Kaplan explained. The mutually beneficial relationship between the development of photography and stereoscopy created a parlor culture in Victorian society, with stereoscopes appearing in classrooms and archival collections. While the three-dimensional images provided traveling experiences, they also acted as souvenirs, like postcards. During World War II, extensive military sets were even used for training. Human anatomy sets were also available for medical industries. The largest producers of stereographs between 1850 and 1915, Keystone Company and Underwood & Underwood, printed descriptions on the back of the mounted cards or had supporting guidebooks, always supplementing the images with additional information. At the turn of the 20th Century, Underwood & Underwood commissioned salesmen to travel extensively and take orders from homes. Since it was extremely easy to acquire new stereographs, the price of the hobby remained affordable. A standard Holmes stereoscope with a sliding carrier to hold the stereographs, could be purchased in 1908 for only 28 cents, while aluminum versions with varnished cherry wood frames were sold for 49 cents (about $11 today). The decline of stereographs began in 1929 with the introduction of the halftone printing process, and photographic details became lost. As very little new content was produced and fake stereographs with identical pictures circulated, the stereoscope faced obsolescence.

But stereoscopic images themselves remained a resilient medium. The format evolved from mounted prints on 3½ by 7-inch cards, to 35mm filmstrips and eventually into 3 ½-inch paper discs with Kodachrome images. In 1931, prior to the View-Master, the company Tru-Vue released black and white stereoscopic filmstrips, each of which had 14 pictures on them that passed through the little viewer horizontally. This competitor was bought by View-Master fairly quickly, and while they tried to release rectangular cards under the Tru-Vue brand (which scrolled through the viewers in a downward fashion rather than rotate), the alternative format lapsed. By the time Portland-based William Gruber presented it at the 1939 World’s Fair in New York, the View-Master’s patented reel and streamlined viewer was unchallenged, and continued to be marketed successfully throughout the Depression.

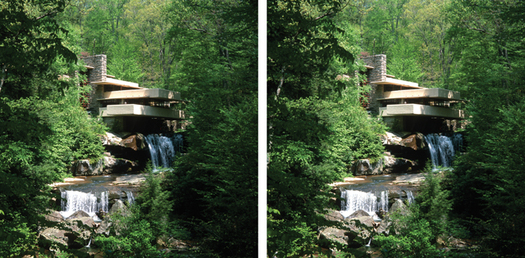

Fallingwater (1937) from Fallingwater: Wright & the 3rd Dimension. Photo: ©1998 View*Productions Fallingwater is a registered service mark of Western Pennsylvania Conservancy

Fallingwater (1937) from Fallingwater: Wright & the 3rd Dimension. Photo: ©1998 View*Productions Fallingwater is a registered service mark of Western Pennsylvania Conservancy Millennium Park (2004) from Frank Gehry: 3 Theaters. Photo: ©2010 View*Productions

Millennium Park (2004) from Frank Gehry: 3 Theaters. Photo: ©2010 View*Productions“When people think of them from their childhood, back in the 1950’s, they think of the black and brown ones,” stated Kaplan, remembering the viewers that were produced in a sturdy, shock-resistant Bake-Lite plastic. But the slow compression-molding process of Bake-Lite was too costly for the rapid demand in viewers. So in 1958, Charles Harrison updated the shape and materials of the Model F View-Master, replacing the original Sawyer design with a beige plastic. While the format of the standardized reels never changed, the viewer went through several redesigns under different brands, embracing a bright red plastic after it was acquired by GAF, and eventually various shapes and colors as it was marketed solely to children under the Fisher-Price brand.

In 2008, Fisher-Price stopped producing View-Master reels after progressively losing interest in what they felt was a low-tech, antiquated medium. Although they spun off a photographic lab called Alphacine a year later, traditional stereoscopic photography has since become a kind of retro novelty. President of the National Stereoscopic Association Lawrence Kaufman feels the images were too small and believes more potential lies in motion pictures, gaming and HD television. But there is an intimate feeling when holding a mere 7 still images in your hands and experiencing those life-like captured moments.

Holmes Stereoscope and Stereo Card from Keystone Company. Photo: Cheryl Yau

Holmes Stereoscope and Stereo Card from Keystone Company. Photo: Cheryl Yau "Spider-Man versus Doctor Octopus" View-Master Reel. Photo: Cheryl Yau

"Spider-Man versus Doctor Octopus" View-Master Reel. Photo: Cheryl YauWhile my 1979 Spider-Man reel enhanced the action of Doctor Octopus reaching through spiderwebs in classic Marvel style, Kaplan’s photography invited me into Russell Wright’s landmarked Dragon Rock home and to the workplace of Charles and Ray Eames. Here, I witnessed classic, mid-century modern design through a stereoscopic lens that recorded the texture and depth of all the designs just as they were produced decades ago — a perspective that Google images and digital reproductions could never provide. I saw the tactile grain of the wooden furniture, the reflections on the glass panels, the light, shadows and wrinkles in his shirt as Charles grasped onto Ray’s pinky with his fingers. To witness these images first-hand is to instantly understand Kaplan’s life-long enthusiasm for 3D images.

View*Productions created a revived interest in View-Masters, appealing to designers and architects who tend, by nature, to be hoarders of ephemera. But at $10 a reel, it has become unprofitable to produce for a niche market. As emerging technologies introduce ever new genres of media, the production of View-Master reels may finally come to an end. Though eclipsed by more contemporary media, their legacy remains indisputable: created long before the advent of mobile technologies, these devices elevated our sense of what was possible. Interactive and engaging, they thrived for nearly a century as powerful conduits and emblems of time travel. And this, perhaps more than anything, represented optimism through design.