William Drenttel|Baseball, Slideshows

February 24, 2008

Any Baseball is Beautiful

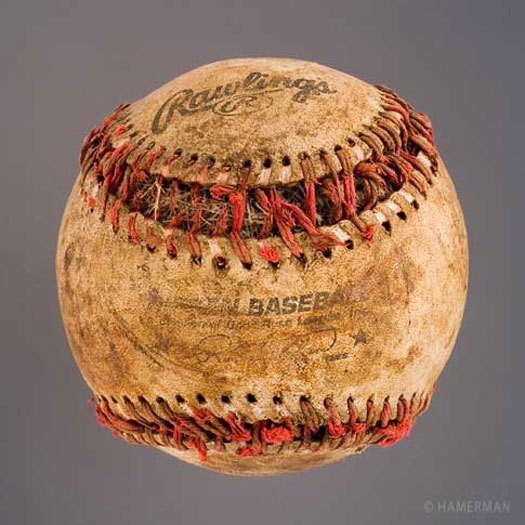

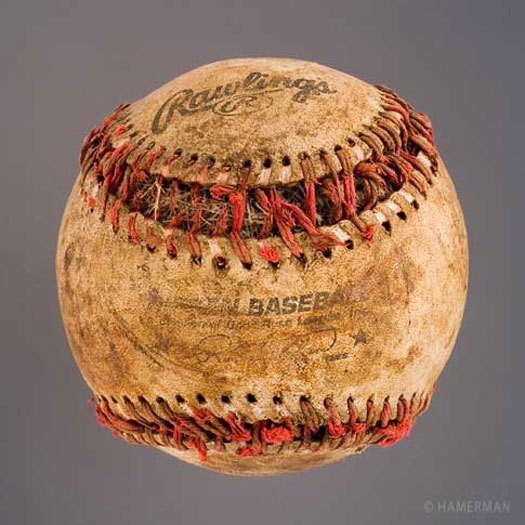

Photograph by Don Hamerman, “Rawlings,” 2005

Spring training opens Wednesday, February 27. I’m not personally a baseball fan and I barely follow the sport, but I hear about this date every year as millions of fans look to the coming season. It is in this spirit of national reawakening that I stumbled upon the photographs of Don Hamerman, a photographer in Stamford, Connecticut. For the past few years, as he’s walked his dog at a local park, he’s picked up lost and forgotten baseballs. There are dozens of them now, all lovingly photographed.

We’ve run a number of recent essays on Design Observer about “things” — objects that are saved or collected or perhaps, on some level, simply fetishized. Most things, though, are made of something, or constructed by someone, or maybe even designed. Often, in their decomposition, they reveal themselves as having parts and materials, a mode of making, and perhaps even a soul. This is the territory of these photographs.

On the subject of baseball — not the sport but the ball itself — no one has written more eloquently than Roger Angell. To accompany these amazing photographs, here is the first paragraph from Angell’s essay, “On the Ball: Spring 1976,” excerpted from his 1976 book, Five Seasons: A Baseball Companion:

It weighs just over five ounces and measures between 2.86 and 2.94 inches in diameter. It is made of a composition-cork nucleus encased in two think layers of rubber, one black and one red, surrounded by 121 yards of tightly wrapped blue-gray wood yarn, 45 yards of white wool yarn, 53 more yards of blue-gray wool year, 150 yards of fine cotton yarn, a coat of rubber cement, and a cowhide (formerly horsehide) exterior, which is held together with 216 slightly raised red cotton stitches. Printed certifications, endorsements, and outdoor advertising spherically attest to its authenticity. Like most institutions, it is considered inferior in its present form to its ancient archetypes, and in this case the complaint is probably justified; on occasion in recent years it has actually been known to come apart under the demands of its brief but rigorous active career. Baseballs are assembled and hand-stitched in Taiwan (before this year the work was done in Haiti, and before 1973 in Chicopee, Massachusetts), and contemporary pitchers claim that there is a tangible variation in the size and feel of the balls that now come into play in a single game; a true peewee is treasured by hurlers, and its departure from the premises, by fair means or foul, is secretly mourned. But never mind; any baseball is beautiful. No other small package comes as close to the ideal in design and utility. It is a perfect object for a man’s hand. Pick it up and it instantly suggests its purpose; it is meant to be thrown a considerable distance — thrown hard and with precision. Its feel and heft are the beginning of the sport’s critical dimension; if it were a fraction of an inch larger or smaller, a few centigrams heavier or lighter, the game of baseball would be utterly different. Hold a baseball in your hand. As it happens, this one is not brand-new. Here, just to one side of the curved surgical welt of stitches, there is a pale-green grass smudge, darkening on one edge almost to black — the mark of an old infield play, a tough grounder now lost in memory. Feel the ball, turn it over in your hand; hold it across the seam or the other way, with the seam just to the side of your middle finger. Speculation stirs. You want to get outdoors and throw this spare and sensual object to somebody or, at the very least, watch somebody else throw it. The game has begun.

Roger Angell © 2004. Published by Bison Books/University of Nebraska Press.

Observed

View all

Observed

By William Drenttel

Recent Posts

Candace Parker & Michael C. Bush on Purpose, Leadership and Meeting the MomentCourtney L. McCluney, PhD|Essays

Rest as reparations: reimagining how we invest in Black women entrepreneurs Food branding without borders: chai, culture, and the politics of packaging Why scaling back on equity is more than risky — it’s economically irresponsible