January 13, 2011

Bushpunk and the Future of Africa

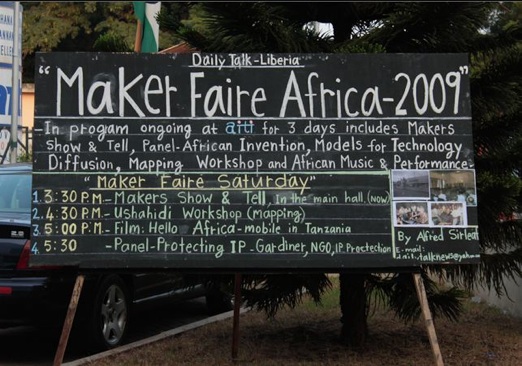

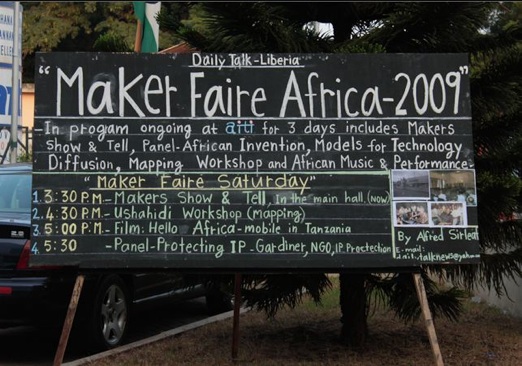

A day’s events at Maker Faire Africa 2009 in Accra, Ghana. Photo: Nathan Cooke

Our journey has never been one of short-cuts or settling for less. It has not been the path for the faint-hearted, for those who prefer leisure over work, or seek only the pleasures of riches and fame. Rather, it has been the risk-takers, the doers, the makers of things — some celebrated but more often men and women obscure in their labor — who have carried us up the long, rugged path towards prosperity and freedom.

Barack Obama

In August 2009, a group of inventors met to share the expressions of their ingenuity — objects assembled from humble materials for comfort or entertainment. They trotted out homemade radios, sheet plastic pressed from recycled bags and sewn into colorful sandals, and a chair constructed from bicycle frames. Technology journalists hung around with video cameras and sent their reports chattering out into the blogosphere. The scene was like many festivals celebrating technological prowess. What made this occasion different was its name and location. Maker Faire Africa took place in Accra, Ghana, where tinkering is anything but a trivial pursuit.

DIY, or do-it-yourself, is a vital activity in many parts of the world, with profoundly different meanings and purposes. In the United States, a burgeoning DIY movement is a reaction to the easy, cheap flow of factory-made goods that have come to signify a world of waste and exploitation. The movement cherishes handwork for its ritualistic, meditative qualities — features that might as easily be characterized as tedious and inefficient. It finds emotional value in the surplus of time and attention devoted to the production of individual pieces or limited editions.

American DIY looks back fondly to eras such as the 1970s, when hippies and other anti-establishment members reviled machines and doted on craft. But it also embraces post-industrial technologies that give the creator new powers, from desktop prototyping tools to web-based marketing software. Its flagship print publications are ReadyMade, which appeals to independent-minded, cash-strapped consumers in their twenties; and Make Magazine, which celebrates the bricoleur’s curiosity and self-reliance and which launched the first Maker Faire in the San Francisco Bay Area in 2006. Flagship websites range from technology blogs like Gizmodo to online craft marketplaces like Etsy.

American DIY, in short, is meta-nostalgic (hankering after epochs that hankered after epochs before them), character-driven, utopian, and founded on privilege. Many adherents have probably never experienced serious privation. Those who champion slowness have the leisure to do so. The great majority of American tinkerers, weavers, hackers, beaders, potters and knitters are in it for recreation, not subsistence — vastly different impulses from those who practice DIY in sub-Saharan Africa.

In Africa, DIY, which ranges across everything from ancient ethnographic crafts to jury-rigged low-tech gadgets, isn’t a movement but a long, unwavering tradition. Rather than representing defiance against mass production, it is often the only available means to supply impoverished communities with functional objects. Practitioners tend to be self-trained, isolated from any network of fellow innovators, and dependent on discarded or repurposed materials for their creations (bodies of work that have been characterized as “bushpunk” or “junkbot”): they recycle not as an environmental principle but as a first and last resort. This was certainly true of many of the bricoleurs who attended MakerFaire Africa 2009 in Ghana. Indeed, the chance to bring them together to inspire one another, and to provide them with access to manufacturing interests and educators, is why Emeka Okafor organized the event, and reprised it in Nairobi, Kenya, in August 2010.

Okafor, a New York–based blogger and entrepreneur from a Nigerian family, believes Africa’s future depends on creating a manufacturing base from its own broad pool of innovators. Although the continent once held the promise of an industrial revolution with its actively mined caches of minerals and ore, progress was stymied by colonialism, which diverted resources to Europe, and then again by hard-won independence. “African elites looking to find their place with other developed parts of the world thought they could buy the knowledge rather than develop it from within with whatever they had,” Okafor told me when we met last June. “They thought they could buy a turnkey factory without knowing how to run it.” While attention was focused on complicated imported machinery that was expensive to acquire, maintain and operate, a whole sector of small producers who could have provided the foundation for African industrial growth, was neglected if not actively squelched.

In 2002, the German economist Wolfgang Schneider Barthold, whose work is cited by Okafor, made this analysis:

…while the [African] elites did everything to drive ahead the industrialization of their countries by means of leaps in modernization, they did very little to at least at the same time promote the step-by-step and organic development of the local small-scale and micro-enterprise sector. Almost all measures which promoted the modern sector hurt the “small people,” either because they raised the hurdles for their legal and formal existence (expenditure of work and time, charges), or by distorting competition and harming or depriving them of their livelihoods.

Since 2003, Okafor has been trying to bring the “small people” to light by tracking their activities on his blog Timbuktu Chronicles, which is described as “a view of Africa and Africans with a focus on entrepreneurship, innovation, technology, practical remedies and other self-sustaining activities.”

Over the past seven years Okafor has published scores of examples of innovators. Trashy Bags, a company in Ghana, organizes the collection of discarded plastic sachets that originally held water or ice cream, and transforms them into tote bags and backpacks. According to the company’s website, 22,000 tons of plastic waste were produced in the capital city Accra in 2008, a 70 percent increase over a ten-year period. Trashy Bags offers a means of recycling the material while employing almost 100 local workers to collect and wash the bags and dozens of others to sew them into sellable products.

Picking up information from the DIY technology website Afrigadget, which was founded by Erik Hersman, Okafor also devoted several postings to the work of the Kenyan inventor Dominic Wanjihia, who turned up at MakerFaire Africa 2009 with a unit to refrigerate camels’ milk for Somaliland herders. The device, a corrugated iron box lined with wet fabric and punctuated with strategically placed vents, cools through evaporation. Later Wanjihia invented a paradoxical-sounding flat parabolic mirror that can be easily packed and transported. Another of Okafor’s exemplars of a community-spirited approach to design is Seyoum Goitom, a self-taught inventor from Eritrea, who created a solar-powered cooker from a satellite dish wrapped in metal foil. Operable without cooking fuel, the device works in deforested regions, like Goitom’s own.

The undeniable star of African invention blogs and Maker Faire Africa is William Kamkwamba. As a 15-year-old living on his parents’ drought-ravaged farm in Malawi, Kamkwamba built a windmill from scavenged materials: bits of wood, nails, and wire; a used battery; a bicycle wheel. He based his design on models illustrated in engineering books he found in his school library, even though he couldn’t read the English-language text. Despite being gently ridiculed by his neighbors, he persisted until he was able to produce electricity, a rare commodity in his world. Lauded by journalists and social change leaders, Kamkwamba, now 23, became a symbol of African innovation. A book about his windmill led to appearances on Good Morning America and The Daily Show. A documentary film is in the works.

“William is a very good example of what I would call a hidden army of people, as opposed to being singular and unique,” Okafor believes. “In any population there’s only a percentage that are leaders. But I would contend that the percentage isn’t less in sub-Saharan Africa than anywhere else.”

Timbuktu Chronicles also suggests strategies for pulling the continent out of its economic quagmire. For example, Okafor argues for the “sexiness” of metalworking and other heavy industrial sectors. Africans may find more of a siren’s call in information communication technology, and there is no shortage of software conferences on the continent, he notes, but he believes there must still be bricks-and-mortar factories turning out physical objects. And at this point, he laments the paucity of industrial design education in Africa.

Okafor finds promise in the hybridization of innovation. “I don’t see why a roboticist can’t talk to a textile designer,” he says. “Why a sculptor can’t talk to a person working in agriculture.” When connections are made between the continent’s crafters and tinkerers, its hackers and digerati, its educators and engineers, and then mixed with venture capital, profitable businesses should result. “If we don’t have this culture of production, we can pump in as much money as we like, build as many schools as we like, as many health facilities…,” Okafor says, trailing off as if to vocally illustrate the empty results of misapplied foreign aid.

In Africa, DIY may not represent an American-style philosophy of anti-industrialism, but, as the initials suggest, it does reflect a parallel attitude of self-sufficiency. People who might be considered marginalized because of their youth or advanced age, gender, lack of formal training or state of social or political oppression assume important creative roles. In Bamako, Mali, a group of women have earned income since the 1970s by skillfully dying cloth for export. In Nairobi, Kenya, Jane Ngoiri has propelled herself out of the Mathare Valley slum by transforming second-hand clothing into wedding and other festive garments. In Cameroon, Lekuama Ketuafor meticulously hand-glues pieces of bamboo to create mosaic-patterned cell phone covers and laptop cases and sells them under the brand name Bamboo Magic.

African makers also frequently contribute to community welfare. Once William Kamkwamba’s neighbors in Malawi stopped laughing at his quixotic effort to build a windmill, they dropped by the farm to power their cell phones. On a vastly more demanding scale, the Ushahidi Project represents the postindustrial bricoleur manipulating cheaply acquired digital material for the public good. Launched by Ori Okolloh, Erik Hersman, and Juliana Rotich to report on violence against opposition party supporters in Kenya’s disputed 2008 presidential election, Ushahidi (“testimony” in Swahili) is a distributed marketplace of information related not to consumables but to disasters. A software program developed through open-source technology aggregates data supplied via cell phone by witnesses and victims of global crises. Against the disinformation transmitted by Kenya’s corrupt mainstream media or the chaos of Haiti’s earthquake or the obstructions of a snow-deluged Washington, D.C., Ushahidi helped protestors navigate escape routes, rescue workers find survivors and highway drivers gain access to plowed roads. What does this have to do with the African model of tinkering? As described by The New York Times, “Ushahidi also represents a new frontier of innovation. Silicon Valley has been the reigning paradigm of innovation, with its universities, financiers, mentors, immigrants and robust patents. Ushahidi comes from another world, in which entrepreneurship is born of hardship and innovators focus on doing more with less, rather than on selling you new and improved stuff.”

The current collaborative opportunities provided both by digital communications and analog events, such as Maker Faire Africa, offer the promise of giving new ideas greater purchase. The endogenous model for development embraced by Emeka Okafor and others is one that offers hope not just for the African continent but also for the world.

A version of this essay originally appeared in The Global Africa Project (Prestel USA), a catalog published in conjunction with an exhibition of the same name on view through May 15, 2011, at New York’s Museum of Arts and Design, Lowery Stokes Sims and Leslie King-Hammond, curators. Thanks to Vera Sacchetti for her invaluable research assistance with this article.

Observed

View all

Observed

By Julie Lasky

Related Posts

Business

Courtney L. McCluney, PhD|Essays

Rest as reparations: reimagining how we invest in Black women entrepreneurs

Design Impact

Seher Anand|Essays

Food branding without borders: chai, culture, and the politics of packaging

Graphic Design

Sarah Gephart|Essays

A new alphabet for a shared lived experience

Arts + Culture

Nila Rezaei|Essays

“Dear mother, I made us a seat”: a Mother’s Day tribute to the women of Iran

Recent Posts

Minefields and maternity leave: why I fight a system that shuts out women and caregivers Candace Parker & Michael C. Bush on Purpose, Leadership and Meeting the MomentCourtney L. McCluney, PhD|Essays

Rest as reparations: reimagining how we invest in Black women entrepreneurs Food branding without borders: chai, culture, and the politics of packagingRelated Posts

Business

Courtney L. McCluney, PhD|Essays

Rest as reparations: reimagining how we invest in Black women entrepreneurs

Design Impact

Seher Anand|Essays

Food branding without borders: chai, culture, and the politics of packaging

Graphic Design

Sarah Gephart|Essays

A new alphabet for a shared lived experience

Arts + Culture

Nila Rezaei|Essays

Julie Lasky is editor of Change Observer. She was previously editor-in-chief of

Julie Lasky is editor of Change Observer. She was previously editor-in-chief of