May 20, 2005

But Darling of Course it’s Normal: The Post-Punk Record Sleeve

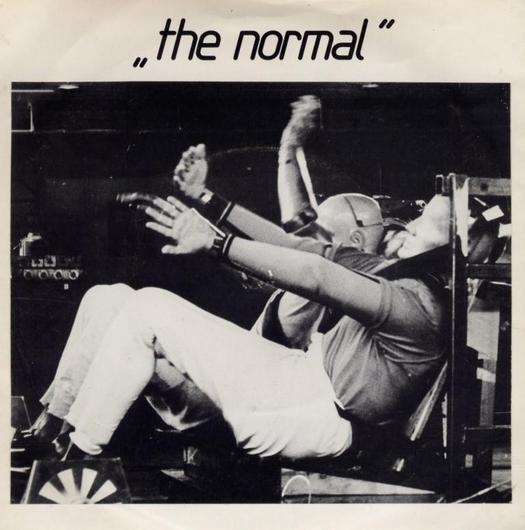

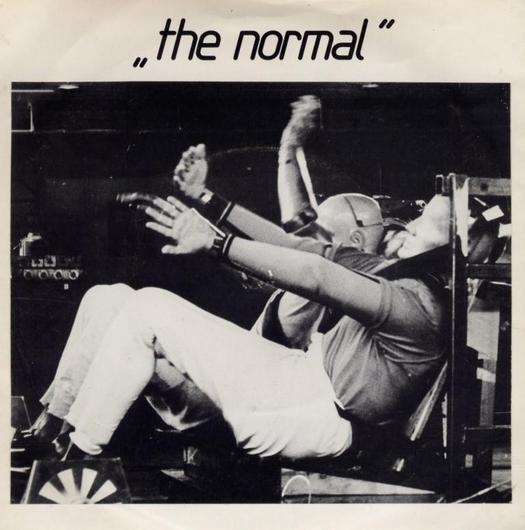

“T.V.O.D. / Warm Leatherette” by The Normal, Mute Records, 1978

In the last few years, there has been a revival of interest in the music that came after mid-1970s punk. Bands from the Red Hot Chili Peppers to Franz Ferdinand acknowledge their debt to post-punk originals such as Gang of Four. The latest issue of The Wire magazine has an ad for a compilation of underground Brazilian groups citing the British post-punk bands Joy Division, The Slits and The Pop Group as influences. There have been collections of post-punk music and now, finally, there is British music critic Simon Reynolds’ 500-page history of the genre from 1978 to 1984, with the invigorating title Rip it Up and Start Again. It’s a brilliant book. Reynolds, who lives in Manhattan, started researching it in 2001 and it has arrived at exactly the right moment to benefit from, and propel, the growing wave of interest. He argues that post-punk music’s explosion of creativity equals the golden age of popular music in the mid-1960s, but that it has never received its full due. I think he’s right.

Design has always been a key part of the record-savouring experience for many music fans and it remains so today, as Momus noted in a recent post. There is a continuing fascination with record covers of the post-punk period. Dot Dot Dot has published pieces about the sleeve designs of XTC, John Foxx, Scritti Politti and Wire — its editors were kids when they came out. Most notable of all was the rapturous reception accorded to Peter Saville’s exhibition at the Design Museum in 2003. British journalists seemed almost as besotted as Saville himself with what he had achieved at Factory Records in the early 1980s and even the London Review of Books sent along their man (novelist Andrew O’Hagan) to check it out.

The latest compendium of post-punk music graphics is This Ain’t No Disco: New Wave Album Covers by New York designer and author Jennifer McKnight-Trontz. I wish I could recommend it, but it’s a lamentable piece of work as cloth-eared when it comes to the music as it is blind to the visual qualities and impervious to the cultural significance (or lack of it) of the artefacts it both includes and arbitrarily leaves out. First published by Chronicle and taken up in the UK by Thames & Hudson, it shows little sign of having passed through the hands of anyone who knows or cares much about the subject. Its interpretation of “new wave” is so loose that it lacks any credibility and many of the covers display no design originality while the bands they represent have rightly been forgotten — Katrina and the Waves, anyone? Kajagoogoo?

Meanwhile, memorable covers that clothed some of the most original post-punk releases, music that still exerts an influence, fail to make the grade. Here are just a few: Pink Flag, Chairs Missing and 154 by Wire; Cut by The Slits; Public Image and Metal Box by Public Image Ltd; Y by The Pop Group: 20 Jazz Funk Greats by Throbbing Gristle; Unknown Pleasures by Joy Division; The Correct Use of Soap by Magazine; Hex Enduction Hour by The Fall. There is nothing by Neville Brody for Cabaret Voltaire or Fetish Records and, with just one cover shown, Vaughan Oliver’s ravishing body of work for 4AD, so prominent in the 1980s, barely gets a look-in. If Roxy Music and Kraftwerk qualify as new wavers, then why not former Roxy band member Brian Eno and the German avant-gardists Can? They were both a big influence on post-punk bands and they had good covers. (Eno produced the Talking Heads album, Fear of Music, which indirectly gives the book its title.) McKnight-Trontz includes Iggy Pop’s Party (1981), presumably because it looks like “fun” with its cleaned-up, presentable Iggy and colourful blobs and splatters, but excludes The Idiot (1977) with its bleak, unsettling, black and white portrait of the singer: what did he mean by those peculiar hand gestures? Someone who understood the music’s impact would be unlikely to make a misjudgement like that.

This may seem inconsequential — they are only record sleeves, after all — but what makes post-punk so interesting and inspiring, even now, as Reynolds shows so well, is the exceptional range of cultural influences that shaped the music, its refusal to stand still, its disinclination to cede any ground, especially to commercial priorities, and its intellectual energy and artistic ambition. All of this was reflected in the most inventive, audacious cover art of the time. “Those seven post-punk years from the beginning of 1978 to the end of 1984 saw the systematic ransacking of twentieth-century modernist art and literature,” he writes. “The entire period looks like an attempt to replay virtually every major modernist theme and technique via the medium of pop music.”

“Being Boiled” by The Human League, Fast Product, 1978

The bands’ sources included Futurism, Dada, Marcel Duchamp, Alfred Jarry, John Heartfield, Constructivism, De Stijl, the Bauhaus, Die Neue Typographie, Bertolt Brecht, the Situationists, Jean-Luc Godard, Anthony Burgess’ A Clockwork Orange, and the extreme science fiction of William Burroughs, J. G. Ballard and Philip K. Dick. Many of the musicians had studied art or design. Talking Heads’ David Byrne put in time at RISD, members of Wire attended Hornsey Art College, Gang of Four were in Leeds University’s fine art department, where the head, art historian T. J. Clark, had belonged to the Situationist International. (It’s a long list. For the best account of art school influences on British rock, see Simon Frith and Howard Horne’s Art into Pop — Reynolds acknowledges his debt to the book.) The sleeve designers — Bob Last at Fast Product, Saville at Factory, Malcolm Garrett in his collaboration with the Buzzcocks, Brody at Fetish — shared many of these influences.

Any visual survey of post-punk graphics that concentrates solely on album covers overlooks a crucial part of the story. The discovery that it was possible to record, manufacture and distribute records relatively cheaply spurred the development of a thriving independent scene. The 7-inch and then 12-inch single with picture sleeve went through a great flowering. 1978 saw the arrival of an advance guard of lo-fi synthesiser singles that heralded a new direction for electronic pop in the 1980s: “T.V.O.D. / Warm Leatherette” by The Normal; “Being Boiled” by The Human League; “United” by Throbbing Gristle; Cabaret Voltaire’s four-track Extended Play; “Paralysis” by Robert Rental; “Private Plane” by Thomas Leer.

“Private Plane” by Thomas Leer, Company/Oblique, 1978

It’s hard to convey the excitement that records like these generated among music fans at the time. A large part of it was the feeling that the usual channels had been bypassed. Only committed readers of the music press were in on it. No one else had a clue. The audience had taken control of the means of production and anything seemed possible. It was a new kind of do-it-yourself electronic folk culture and the kitchen-table designs that gave this sensibility an image were raw but thrilling. The photo of crash test dummies, borrowed from the Motor Industry Research Association, and use of the Din typeface to represent Daniel Miller’s “Warm Leatherette” underscores the cold, sociopathic lyrics about the eroticism of a car crash (“Hear the crushing steel, feel the steering wheel”). Listeners instantly registered the song as a homage to Ballard’s cult novel Crash. This Ain’t No Disco breaks its own remit by featuring a few singles, none of them shown here, but it largely misses this side of post-punk music. One of the pleasures of Reynolds’ book is its excellent picture research with the assistance of British music writer Jon Savage.

With thanks to Hilary Young

See also:

The Art of Punk and the Punk Aesthetic

It’s Smart to Use a Crash Test Dummy

Observed

View all

Observed

By Rick Poynor

Related Posts

Business

Courtney L. McCluney, PhD|Essays

Rest as reparations: reimagining how we invest in Black women entrepreneurs

Design Impact

Seher Anand|Essays

Food branding without borders: chai, culture, and the politics of packaging

Graphic Design

Sarah Gephart|Essays

A new alphabet for a shared lived experience

Arts + Culture

Nila Rezaei|Essays

“Dear mother, I made us a seat”: a Mother’s Day tribute to the women of Iran

Recent Posts

Minefields and maternity leave: why I fight a system that shuts out women and caregivers Candace Parker & Michael C. Bush on Purpose, Leadership and Meeting the MomentCourtney L. McCluney, PhD|Essays

Rest as reparations: reimagining how we invest in Black women entrepreneurs Food branding without borders: chai, culture, and the politics of packagingRelated Posts

Business

Courtney L. McCluney, PhD|Essays

Rest as reparations: reimagining how we invest in Black women entrepreneurs

Design Impact

Seher Anand|Essays

Food branding without borders: chai, culture, and the politics of packaging

Graphic Design

Sarah Gephart|Essays

A new alphabet for a shared lived experience

Arts + Culture

Nila Rezaei|Essays

Rick Poynor is a writer, critic, lecturer and curator, specialising in design, media, photography and visual culture. He founded Eye, co-founded Design Observer, and contributes columns to Eye and Print. His latest book is Uncanny: Surrealism and Graphic Design.

Rick Poynor is a writer, critic, lecturer and curator, specialising in design, media, photography and visual culture. He founded Eye, co-founded Design Observer, and contributes columns to Eye and Print. His latest book is Uncanny: Surrealism and Graphic Design.