December 31, 2009

Chain Letters: Chelsea Mauldin

Mauldin in collaboration with the Louisville Metro Government, Department of Corrections staff, jailed people, and treatment community members while solving for how a jail can create supports to break the cycle of opioid use and incarceration. Image courtesy Chelsea Mauldin.

This interview is part of an ongoing Design Observer series, Chain Letters, in which we ask leading design minds a few burning questions—and so do their peers, for a year-long conversation about the state of the industry.

This November, we’re looking at design and democracy through a different lens: service design, and how it functions within government systems to serve us better.

Chelsea Mauldin is a social scientist and designer with a focus on government innovation. She directs the Public Policy Lab, a New York City nonprofit that designs better public policy and services for low-income and at-risk Americans.

The Public Policy Lab partners with government agencies to develop more satisfying and effective policies and services through ethnographic research, human-centered design, rapid prototyping, and formative evaluation. Find out more on PPL’s website or on Twitter @publicpolicylab.

Mauldin speaking in October 2018 at RSD7 Relating System Thinking and Design Symposium. Image courtesy Chelsea Mauldin.

What are a few key factors you consider when asked to take on a project by a government entity and in determining whether or not your work will have lasting success?

There are four key considerations when taking on a project.

- Scope: Will the project focus on the experiences of low-income or marginalized Americans, and will we have sufficient time and access to understand and deliver policy or service designs that genuinely respond to that public’s needs and preferences?

- Ownership: We most often develop partnerships with people in government who have strategic, future-oriented roles—but for our work to be successfully implemented, it needs to be embraced by people who focus on day-to-day operations.

- Opportunity: What are the opportunities for our design team to substantively partner with operations managers and front-line staff during this project? That’s how we can best design policies and services towards which operations folks will feel ownership and satisfaction.

- Scale: Do our partners have sufficient political buy-in, budget, and timeline to implement successful prototypes at a system level? Working with government means designing in the context of politics. We’ve learned to be leery of beginning complex work too close to the end of a four-year election cycle.

Mauldin and Public Policy Lab fellow Camilla Buchanan conducting research with front-line operations staff. Image courtesy Chelsea Mauldin.

A final key factor is whether we believe our partners will be interested in revisiting the work over the course of years; collaborating with us in understanding what’s worked well and what’s underperformed.

Success is a long game. There’s the immediate goal of delivering work that our partners appreciate and want to put to use. And there are the slightly longer-term effects where work begins to influence the experience of hundreds of thousands or even millions of people, hopefully positively! Our organization is just getting to the point, almost five years since we delivered our first complete project, where we can observe the lasting system effects of Public Policy Lab’s work.

How do you identify opportunities for improvement in a designed system that appears broken?

Most broken government systems are not designed—they accrete, bits and pieces stuck on to address problems, usually on a lagging basis, without good visibility into the impact on the whole system. Breaks occur at temporary welds that were never intended to bear their current load. The breaks are multiple, not singular, so you only have to look in order to find plenty to fix.

Most broken government systems are not designed—they accrete, bits and pieces stuck on to address problems.

We typically begin engagements by conducting in-person qualitative research with, at minimum, agency leaders, service providers, and members of the public. People generally want to share their experiences and what they know, even around topics like poverty or mental illness or addiction. So if a designer shows up—not acting like an expert, but as a guest who genuinely wants to learn what’s going on—there’s a huge amount to discover.

That process generates dozens of concepts for design—from potential new artifacts, like communications or digital tools, to new interaction models and service-delivery programs, to new policy and leadership guidance. The challenge is not in identifying opportunities, but in narrowing the pool of potential interventions to those most likely to create change in the public’s experience, most feasible to fund and implement, and the most likely to get buy-in from everyone from political leadership to front-line staff.

The challenge is not in identifying opportunities, but in narrowing the pool of potential interventions.

Partners often want all the ideas, so we encourage them to participate in our synthesis process, so they see how ideas are generated and refined. But as most designers discover, the project is usually more successful if we move forward with considering only a limited set of the strongest opportunities.

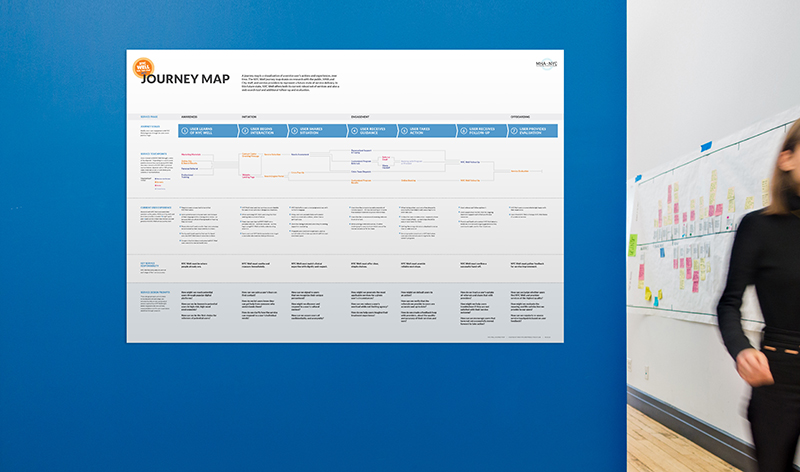

A journey map for NYC Well, a resource created in partnership with Mental Health Association of New York City (now Vibrant Emotional Health) and NYC Department of Health & Mental Hygiene to increase access to NYC’s mental-health services. Image courtesy Chelsea Mauldin.

Does poor information design disproportionately affect some user groups over others, and what are the implications of that relationship?

Poor information design is a drag on everyone, but it creates more problems for people who are already struggling. In a market context, competitive pressures can sometimes inspire service providers to invest in quality information and interaction design that makes even complex processes feel relatively pleasant. Public services for the poor don’t face the same financial pressure to deliver delightful user experiences, and there may even be perverse political pressure that makes accessing services hard. There are obviously malign instances of this (see voter suppression, etc.), but even well-intentioned programs can have bad consequences.

For instance, policymakers sometimes think that if you give people more choices, you are de-facto providing a better service. So we have Medicare Advantage plans or, in New York City, high-school choice. But too many insufficiently distinguishable (or equally unappealing) choices are burdensome, particularly for low-income and marginalized people.

Successful design of public services requires designing policy itself, not just the interface at the point of the end user.

There’s a well-researched relationship between poverty and cognitive load: the more you’re dealing with scarcity, the more difficult it is to process information and extract meaningful factors to drive your choice making. People dealing with illness or trauma or racism face similar challenges. The upshot is that good information design can help over-burdened people navigate complexity— while bad design compounds the problems already experienced by people with restricted resources.

A challenge is that, while programs ideally should be designed to be genuinely respectful and simple to understand, there’s often a limit to the interaction simplification that a designer can affect in complex policy contexts. That’s why we find that successful design of public services often requires also designing policy itself, not just the interface at the point of the end user.

What do government services look like at their best?

Good public services cluster at two extremes:

- Largely automatic, universal services, like Social Security or municipal trash collection, that require limited evidence or actions from the public in exchange for significant social and individual value

- Very high-touch, individualized, person-to-person services for high-need individuals who are poorly served by standardized solutions.

There’s plenty of design work to do to improve the experience of the public in between, though I do suspect that the bulk of our effort should really be in trying to move the mass middle of public service delivery toward one of those two poles.

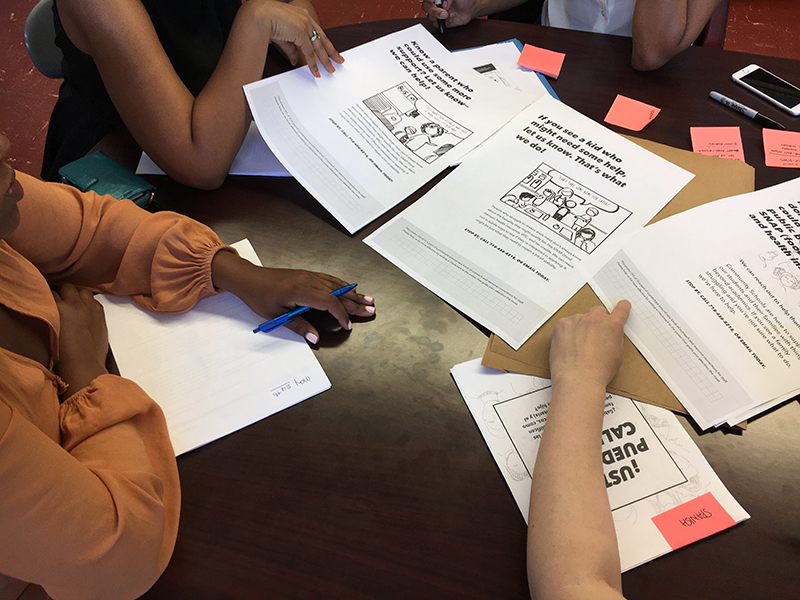

Public Policy Lab staff co-designing prototypes with New York City school school staff to help low-income families better access public benefits. Image courtesy Chelsea Mauldin.

From Steven Heller: How is design for the public good best practiced by designers who are used to being hands for their clients?

‘Being hands’ for our clients is just as necessary a skill for a designer working the public interest—indeed, it’s the whole mission of a human-centered public design practice. Perhaps the only thing that’s different from a commercial practice is that our clients are the public, and the people paying for our services—governments and philanthropies—are our partners in serving those same clients.

The ‘how’ involves a belief in the freedom that comes when you trade being designer-as-hero for designer-as-comrade-in-arms.

The ‘how’ involves an interesting balancing act, between confidence in one’s practiced creative skills as a professional designer and a genuine embrace of other needs, other viewpoints, a real belief in the freedom that comes when you trade being designer-as-hero for designer-as-comrade-in-arms. I often circle back to a quote that’s attributed to a 1970s Aboriginal activists group in Queensland, “If you have come here to help me, you are wasting your time. But if you have come because your liberation is bound up with mine, then let us work together.” We work as we do not out of a spirit of compassion or generosity—we do it selfishly, in the desire to someday enjoy the benefits of being an American in an America where all Americans have the same opportunities.

Next week Chelsea asks Toni L. Griffin, Professor in Practice of Urban Planning at the Harvard Graduate School of Design: What aspects of just urban design practice end up generating the most resistance from residents—or political leaders? How do you address conflict in your work?

Observed

View all

Observed

By Lilly Smith

Related Posts

Design Juice

Delaney Rebernik|Interviews

Runway modeler: Airport architect Sameedha Mahajan on sending ever-more people skyward

Sustainability

Delaney Rebernik|Books

Head in the boughs: ‘Designed Forests’ author Dan Handel on the interspecies influences that shape our thickety relationship with nature

Design Juice

L’Oreal Thompson Payton|Books

Less is liberation: Christine Platt talks Afrominimalism and designing a spacious life

Design Juice

L’Oreal Thompson Payton|Interviews

Cheryl Durst on design, diversity, and defining her own path

Recent Posts

Runway modeler: Airport architect Sameedha Mahajan on sending ever-more people skyward The New Era of Design Leadership with Tony Bynum Head in the boughs: ‘Designed Forests’ author Dan Handel on the interspecies influences that shape our thickety relationship with nature A Mastercard for Pigs? How Digital Infrastructure is Transforming Farming and Fighting PovertyRelated Posts

Design Juice

Delaney Rebernik|Interviews

Runway modeler: Airport architect Sameedha Mahajan on sending ever-more people skyward

Sustainability

Delaney Rebernik|Books

Head in the boughs: ‘Designed Forests’ author Dan Handel on the interspecies influences that shape our thickety relationship with nature

Design Juice

L’Oreal Thompson Payton|Books

Less is liberation: Christine Platt talks Afrominimalism and designing a spacious life

Design Juice

L’Oreal Thompson Payton|Interviews