October 25, 2018

Chain Letters: Elysia Borowy-Reeder

This interview is part of an ongoing Design Observer series, Chain Letters, in which we ask leading design minds a few burning questions—and so do their peers, for a year-long conversation about the state of the industry.

October is archives month, and to celebrate we’re looking at design history through a few key questions. A tall order, we know. Luckily we’ve tapped the best design practitioners and historians from across the globe to tackle it—and to ask each other questions of their own.

As Executive Director of the MOCAD, Elysia Borowy-Reeder plays an essential role in establishing the vision, goals, and strategic plans for the museum. Fulfilling MOCAD’s mission through close collaboration with key stakeholders, she tirelessly works to sustain the museum and to secure its permanent future in Detroit for generations to come. She joined MOCAD as Executive Director in April of 2013. She is former Founding Director of CAM Raleigh and served in leadership positions at MCA Chicago, MAM, and SAIC. Having curated over 40, she holds two master degrees from MSU, was named a 2008 Getty Museum Leadership Fellow, and attended Yale School of Management and Antioch College.

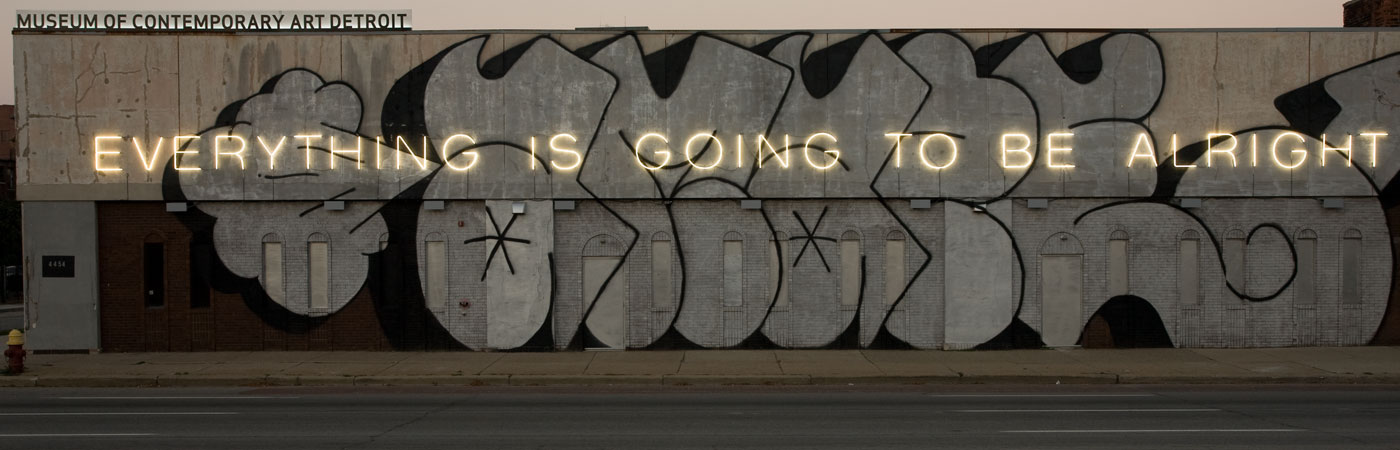

Front of the building by Martin Creed Everything Will Be Alright — Work No.790: EVERYTHING IS GOING TO BE ALRIGHT is a large word-based sculpture made in white neon consisting of a single line of unpunctuated text that reads ‘EVERYTHING IS GOING TO BE ALRIGHT’.56 feet in length and 8 feet in height, the sculpture resembles large-scale commercial neon signage in its proportions. Work No. 790 is consistently displayed well above head height across the façade of a building.

There’s a well-known phrase attributed to Winston Churchill that says, “history is written by the victors.” Is this applicable to our understanding of design history? What’s being done to rewrite it?

It’s such a big question. From my perspective, the biggest course correct to the art history canon is the Feminist art movement that emerged in the late 1960s amidst the anti-war demonstrations and civil rights movements. Going back to the utopian ideals of early-20th century modernist movements, Feminist art created opportunities and spaces that previously did not exist for women and marginalized artists, and paved the way for the Identity art and Activist art of the 1980s and now the social justice projects that we see inside MOCAD today. They focused on intervening in the established art world and the art canon’s legacy, as well as in everyday social interactions, which is why the mission of MOCAD is so important to our community and to me personally. As artist Suzanne Lacy (who I met recently at a Culture Lab Detroit program) declared, the goal of Feminist art was to “influence cultural attitudes and transform stereotypes.”

The Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit is a museum, but it’s also a gathering place where we generate ideas and critical dialogues surrounding the creative process and what it means to be human. In this way we are actively leading and writing a cultural history unique to Detroit and the overarching contemporary art community. We present the Warhols; the Mary Cassatts, of tomorrow. Artists have always been great at pushing for rebellion and challenging the status quo.

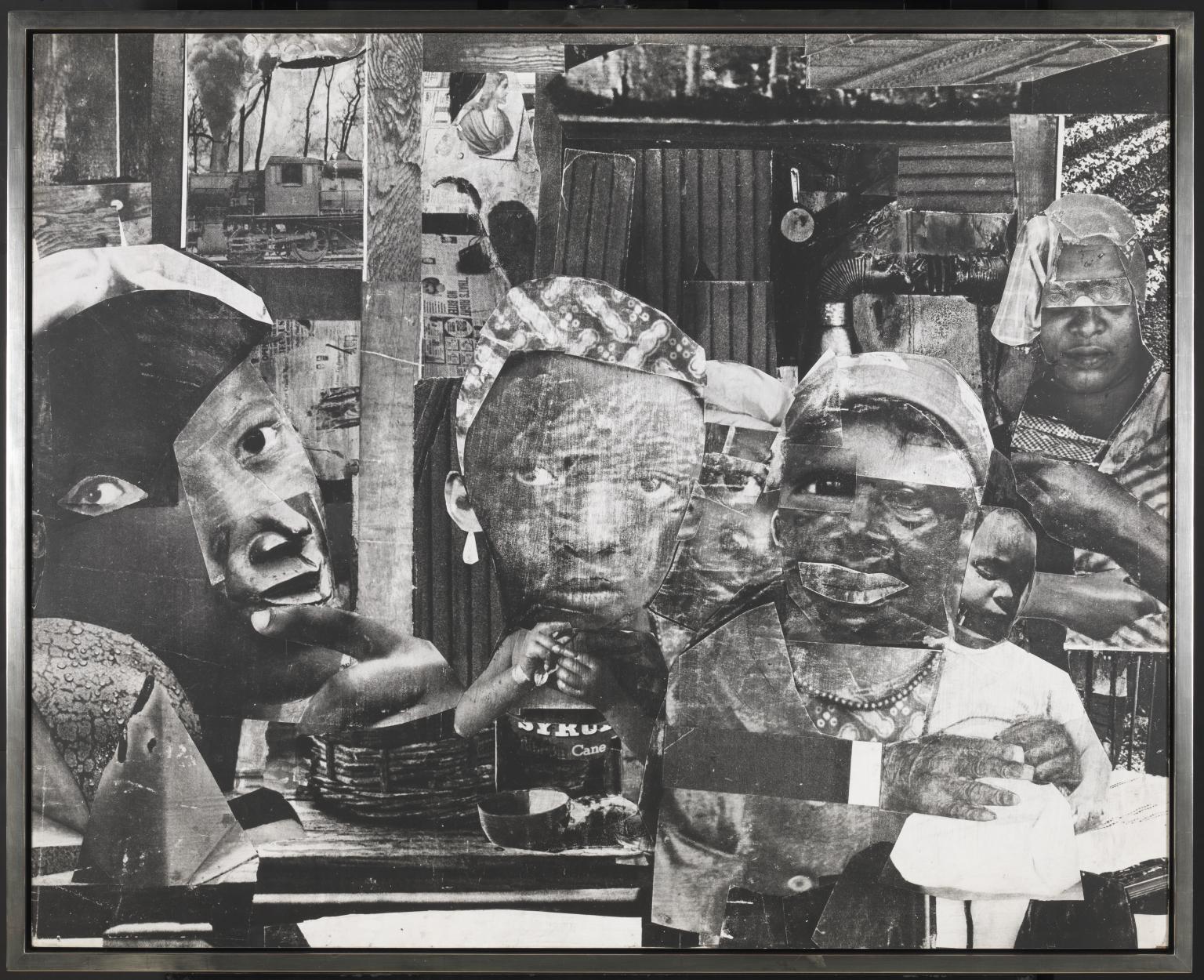

Romare Bearden, Mysteries II, 1964. Photostat mounted on fiberboard. 50 1/2 x 62 1/2 inches. Courtesy DC Moore Gallery, New York Art. © Romare Bearden Foundation/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

In looking back at historical works, can—or should—the quality of the design itself ever be separated from its context?

Can one really separate the art from the person who creates it? The answer is yes, definitely. There are many examples in history—too many I think. But why look at art separately from the artist? Separately from the context in which it is was made? You’ll only get half the story. I want to move the conversation further than art separated from its context. That’s kind of been there done that. What’s more interesting is asking questions that dive deeper into those disciplines with strong, loaded connotations: the nature of craft in functional design and craft in art. Why is craft different than engineering? It has to everything to do with history.

I love what’s happening in the design world right now because the internet allows marginalized fringe voices a front and center seat. If you have an idea that interests you—any idea—you can google it and find it. If you search “styrofoam furniture,” for instance, you’ll find a brilliant designer named Max Lamb. That’s the real conversation. The internet has created the context. Information is everywhere now because it’s accessible. The role of the curator becomes so important, perhaps now more than ever, because none of us can keep up with content being added at such a fast pace. We need educated, well-versed curators to make sense of it all.

Information is everywhere now. We need educated, well-versed curators to make sense of it.

What is your strategy for weaving design history into your work?

When curating, I often explore the inherited frameworks of making, theorizing, and exhibiting art and wonder if the traditional modes still apply to contemporary practice. I also think about the current commodification of the art industry and the distribution of images in the digital age. Drawing from my formation as a maker and a graduate of Antioch College, I think my curatorial work reflects on the spaces of contemporary art—the gallery, the institution, the biennial, the art fair—and ultimately positions the discipline of curating in the context of a larger cultural sphere shaped by the political, social, and economic conditions of its time, while demanding new attitudes and new thinking.

I often explore the inherited frameworks of making, theorizing, and exhibiting art and wonder if the traditional modes still apply. My work demand[s] new attitudes and new thinking.

Museums are a lifelong learning space. MOCAD, in particular, is a gathering space where people can share ideas and experiences; It’s an innovative space where visitors learn about social and historical contexts of our current landscape and understand the life and practice of living artists. We host an expanded selection of education programs, in particular the launch of our teen program, which is designed to foster a new, interactive audience. We work very hard to keep the raw space for art and discussion at the forefront of our planning. For instance, we exist within a repurposed Albert Kahn building. We stand as a pillar of history and a pillar of the future.

Samara Golden, The Meat Grinder’s Iron Clothes. Samara Golden’s site-specific installation for the 2017 Biennial, handmade sculptures of furniture and other everyday objects create a series of environments seemingly in conflict with each other.

Bonus q: Name a designer from the past that people may not know about (but should look up right now).

I’m going to say Mies Van Der Rohe. I currently live in one of his Detroit townhouses. Detroit has the highest saturation of Mies designed building more so than anywhere on the planet. Here in Detroit, we’re fortunate to have a city with great design. Growing up, most Detroiters are surrounded by Eero Saarinen, Mies, Albert Kahn, Charles and Ray Eames, and Yamasaki. Because of the generous landscape that rich in architecture and design, we enter the world with an enhanced, cutting-edge sensibility. You can design an amazing life in Detroit. (One a side note, if I’m to mention someone lesser known, I’d also say Anni Albers for her textile work!)

You can design an amazing life in Detroit.

From Alexander Tochilovsky: In the time you’ve spent working in museums, what’s the most significant change you’ve seen in how people interact with museums today? Is that change more due to the audience or the museums adjusting?

In my opinion, the great twenty-first century museum isn’t about collecting. It’s about public programming and engagement.

Next week Elysia asks Steven Heller: The growth of design schools and certificate programs seems unstoppable. Designers born after 1990 have a totally different view of visual culture, aesthetic products, creative vision, speed of communication, thought processes, and relationship to the world from that of their predecessors. Communication aesthetics are in an ever-temporary state; design has become a dynamic and unstable ever-changing area. All these developments pose new questions to the status of the designer, the curator, and the industry. What do you see as the future for the person who wants to be a “designer?” Are designers artists and artists designers?

Observed

View all

Observed

By Lilly Smith

Related Posts

Arts + Culture

Alexis Haut|Interviews

Beauty queenpin: ‘Deli Boys’ makeup head Nesrin Ismail on cosmetics as masks and mirrors

Design Juice

Rachel Paese|Interviews

A quieter place: Sound designer Eddie Gandelman on composing a future that allows us to hear ourselves think

Design of Business | Business of Design

Ellen McGirt|Audio

Making Space: Jon M. Chu on Designing Your Own Path

Design Juice

Delaney Rebernik|Interviews

Runway modeler: Airport architect Sameedha Mahajan on sending ever-more people skyward

Recent Posts

Beauty queenpin: ‘Deli Boys’ makeup head Nesrin Ismail on cosmetics as masks and mirrors Compassionate Design, Career Advice and Leaving 18F with Designer Ethan Marcotte Mine the $3.1T gap: Workplace gender equity is a growth imperative in an era of uncertainty A new alphabet for a shared lived experienceRelated Posts

Arts + Culture

Alexis Haut|Interviews

Beauty queenpin: ‘Deli Boys’ makeup head Nesrin Ismail on cosmetics as masks and mirrors

Design Juice

Rachel Paese|Interviews

A quieter place: Sound designer Eddie Gandelman on composing a future that allows us to hear ourselves think

Design of Business | Business of Design

Ellen McGirt|Audio

Making Space: Jon M. Chu on Designing Your Own Path

Design Juice

Delaney Rebernik|Interviews