September 4, 2018

Chain Letters: Zachary Lieberman

This interview is part of an ongoing Design Observer series, Chain Letters, in which we ask leading design minds a few burning questions—and so do their peers, for a year-long conversation about the state of the industry.

It‘s August, while it’s still crazy hot and we’d all like to be poolside, it’s time to think about heading back to school. This month, we examine design and education, and look at how education will shape the design discipline of the future.

Zachary Lieberman is an artist, researcher, and educator with a simple goal: he wants you to be surprised. In his work, he creates performances and installations that take human gesture as input and amplify them in different ways—making drawings come to life, imagining what the voice might look like if we could see it, and transforming people’s silhouettes into music. He’s been listed as one of Fast Company‘s Most Creative People, and his projects have won the Golden Nica from Ars Electronica and Interactive Design of the Year from Design Museum London, as well as listed in Time Magazine’s Best Inventions of the Year. He creates artwork through writing software and is a co-creator of OpenFrameworks, an open source C++ toolkit for creative coding, and helped co-found the School for Poetic Computation, a school examining the lyrical possibilities of code.

Graphis Annual 124 — 1966, cover designed by Toshihiro Katayama. “I am fascinated with work that feels algorithmic and features layering and flat 3D.”

How much emphasis do you place on “real life” project-based learning as compared to theoretical design study?

In terms of study, I think the most important thing is history. It’s important to absorb and engage with the past and find a way to recreate the past using modern voice. For a student, I think that is both a gift and an obligation. That said, I am more of a maker than a thinker, and I often find I learn more about what a work is in the process of making it—and even after the fact.

In November, AIGA is publishing “Designer 2025,” the culmination of research led by Meredith Davis and other leaders across multiple sectors, which will identify seven emerging trends with long arcs of influence and describe key competencies necessary to compete in the coming decade. All this begs the question: How can teachers prepare their students for jobs that don’t exist yet?

Tools and jobs will always change but the fundamentals stay the same. I think the best thing teachers can do is to engage with key qualities that make students good students: curiosity and openness.

Tools and jobs will always change but the fundamentals stay the same.

Curiosity is about asking questions. On the first day of a new class at the School for Poetic Computation, which I co-founded, we ask the students to take out a piece of paper and write down all the questions they have that brought them into the room. These questions include very practical ones, like how do I do X or Y, but also unanswerable questions that get to the heart of what we are doing. When they leave the program, I’d like them to have a new set of questions that can become almost like rocket fuel for their creative practice. As a trait, curiosity is also about being an obsessive collector and documenter. I try to model curiosity in the classroom by showing students that it’s ok to be obsessed and collect. Those obsessions can inform your practice.

Openness is about working openly and sharing. I think classrooms should foster open source, collaborative ethos—together we know more. It’s hard to know everything (especially in the tech world, with its layers and layers of abstractions). Learning is really about conversation and collaboration.

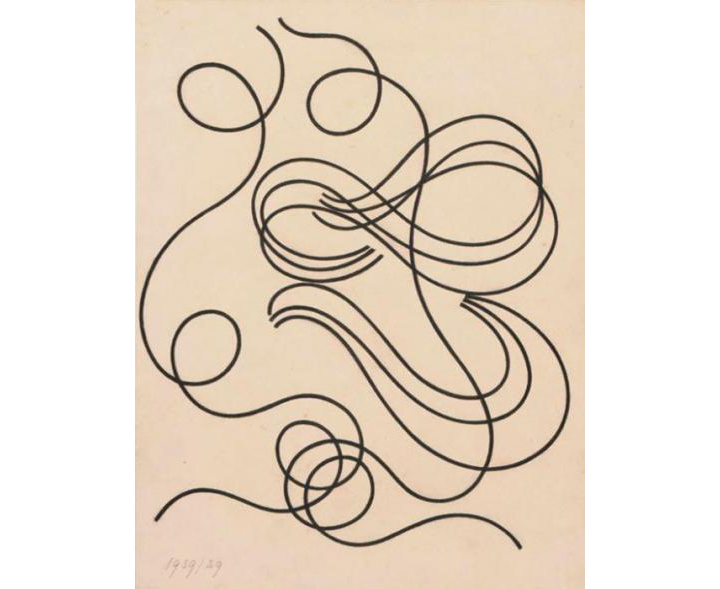

Sophie Taeuber-Arp’s curves are a big inspiration for Lieberman’s work.

There are so many resources available online—YouTube tutorials, MOOCs, an endless supply of design blogs. Does this indicate that learning been democratized, in that there are many ways to get to the same end destination—a position in the design field? Or, has decentralized learning created a lack of a cohesive set of standards?

I think it’s great. People learn and communicate in different ways and I’m floored by what it means to be a student now. I came up before blogs and YouTube, and the way we absorbed and shared information was so different. That said, with more exposure to the world of visual thinking, I think it’s easy for students to get intimidated and feel like everything has already been done. It’s important for a teacher to express a fundamental truth to students: the world is hungry for new ideas, new tools, and new institutions, and there is tremendous space in which to create them.

I also think it’s important to push students to get off the screen. The best things they can learn come through serendipity and chance—like from finding an old book in a bookstore or tumbling upon a random art exhibition. Push them and encourage them to get offline sometimes, too.

It’s important for a teacher to express a fundamental truth to students: the world is hungry for new ideas, new tools, and new institutions, and there is tremendous space in which to create them.

When you reflect on your body of work to date, which has the most personal value for you? Why?

I would have to say the eyewriter project—which is almost 10 years old now. We helped to build an eyetracking device for a paralyzed graffiti writer so he could draw graffiti again. I love this project because it’s about helping someone connect with something that they love to do. It’s really about how technology can help give people new (and old) voices.

Rising of the Setting Sun By Wayne Pate. “I love images that feel computational but are hand drawn, they remind me to bring more hand drawn to my computer work.”

Talk about a professor that improved your design approach. How did they do it?

Observed

View all

Observed

By Lilly Smith

Related Posts

Design Juice

Delaney Rebernik|Interviews

Runway modeler: Airport architect Sameedha Mahajan on sending ever-more people skyward

Sustainability

Delaney Rebernik|Books

Head in the boughs: ‘Designed Forests’ author Dan Handel on the interspecies influences that shape our thickety relationship with nature

Design Juice

L’Oreal Thompson Payton|Books

Less is liberation: Christine Platt talks Afrominimalism and designing a spacious life

Design Juice

L’Oreal Thompson Payton|Interviews

Cheryl Durst on design, diversity, and defining her own path

Recent Posts

Runway modeler: Airport architect Sameedha Mahajan on sending ever-more people skyward The New Era of Design Leadership with Tony Bynum Head in the boughs: ‘Designed Forests’ author Dan Handel on the interspecies influences that shape our thickety relationship with nature A Mastercard for Pigs? How Digital Infrastructure is Transforming Farming and Fighting PovertyRelated Posts

Design Juice

Delaney Rebernik|Interviews

Runway modeler: Airport architect Sameedha Mahajan on sending ever-more people skyward

Sustainability

Delaney Rebernik|Books

Head in the boughs: ‘Designed Forests’ author Dan Handel on the interspecies influences that shape our thickety relationship with nature

Design Juice

L’Oreal Thompson Payton|Books

Less is liberation: Christine Platt talks Afrominimalism and designing a spacious life

Design Juice

L’Oreal Thompson Payton|Interviews