The act of writing is silent these days. In the past, the clickety-clack of manual typewriters (or the gun burst of an IBM Selectric) was the audible cue that work was being done: noise as proof of production. It was impossible to fake it on those metal machines: no email and no surfing, just the hard plain fact of fingers on keys.

A typewriter is a symphony of sounds: the zip of the paper as it feeds around the platen, the rat tat tat of the typebar (the metal stalks with their letter forms) striking the page, the shuddery thud when the shift bar levers the machine up and then drops it back down. And, of course, the cymbal-like ding that punctuates the end of a typed line and signals the rumbling progress of the roller as returns to its starting position.

Typewriter typing, as opposed to laptop typing, is a visceral act. Your hands get dirty (just like doing real work!). When the typebars tangle you have to reach inside the guts of the machine and straighten them out. Your fingers end up smudged with ink when you change the ribbon, become sticky with globs of White Out when you make a mistake. You ram the brush in anyway and everything gets worse: the messy slather of the White Out, the shedding hairs of the brush, the lumpy paper. Impatiently you start typing again. The typebar leaps forward smartly but then sinks illegibly into the mush.

The commercial typewriter was patented in 1869 and transformed the workplace, increasing the number of women behind the keyboard from four percent in 1874 to approximately seventy-five percent in 1900. The individuality of handwriting disappeared from official forms, memos, client letters, receipts, inquiries, bills of sale, court reports, and marriage licenses. The typewriter had industrialized writing.

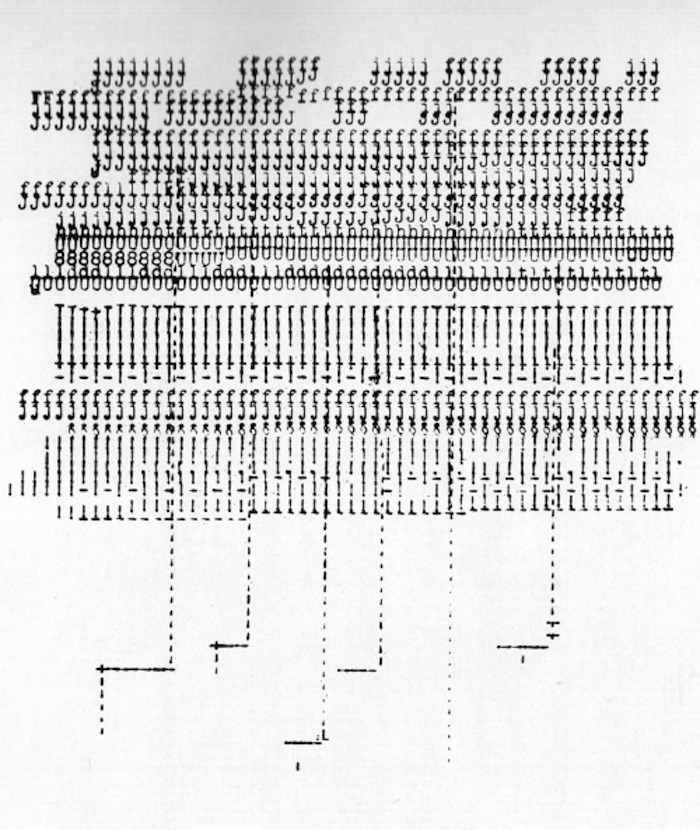

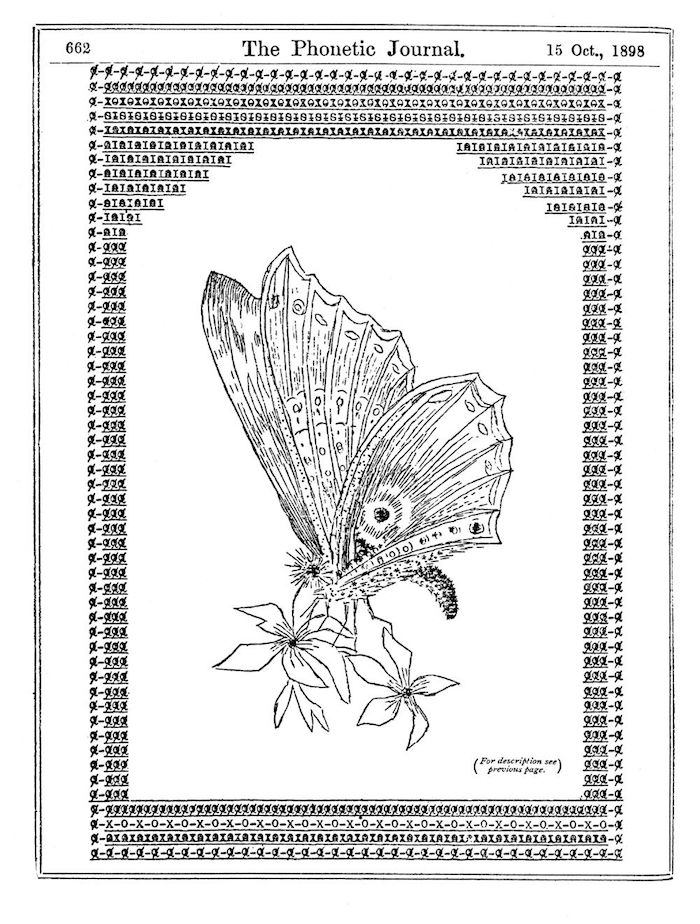

Although typewriter technology was no match for the expressive power of the hand-drawn line, one can also use the keys to produce what has been called “typewriter art.” The first known example is a butterfly made from dashes, brackets, and asterisks made in England by a secretary named Flora Stacey and first published in 1898.

Marvin and Ruth Sackner, in their handsome book

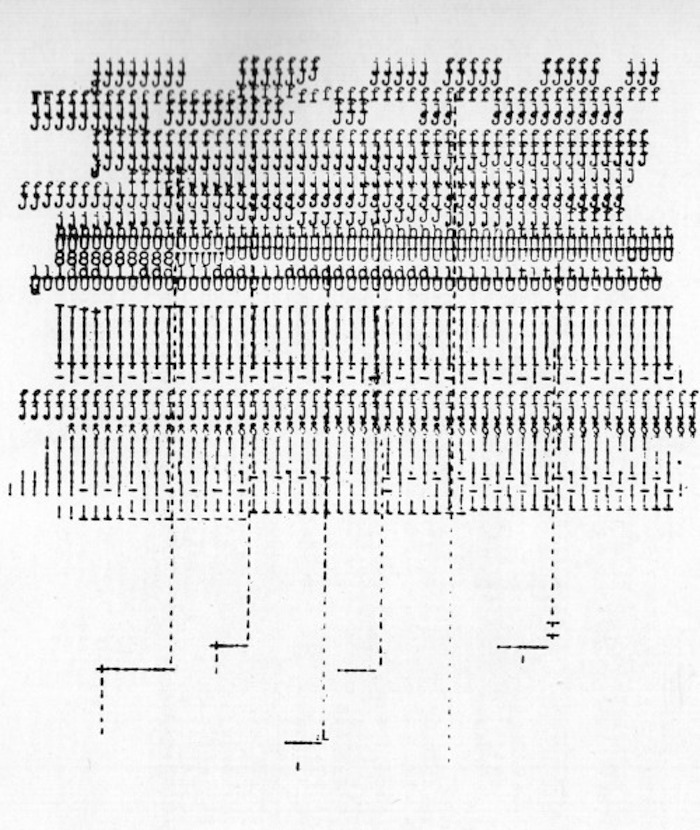

The Art of Typewriting, note that typewriter realism held sway with portraits and flowers until the 1920s and ’30s, when the Constructivists seized on the geometrical potential in the form. Nicolas Werkman (below) made what look like pre-Mondrian Broadway Boogie Woogies in Holland.

At the same time, Pietro de Saga (the pseudonym for the female artist Steffi Kiesler) was producing austerely beautiful compositions (below) before she moved to America and became a librarian.

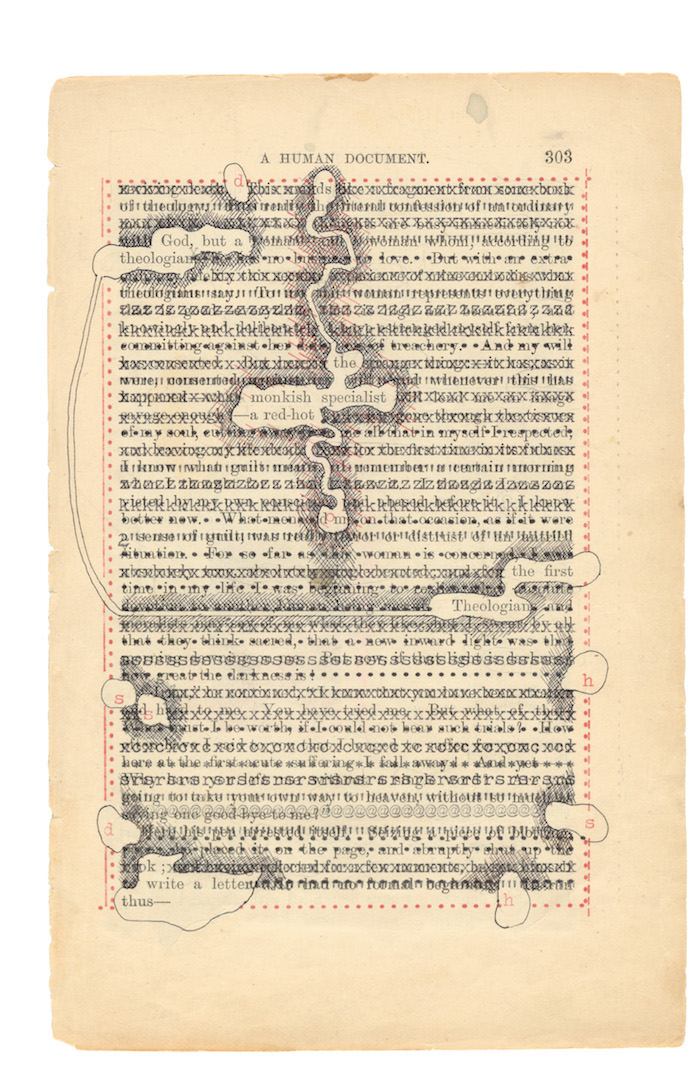

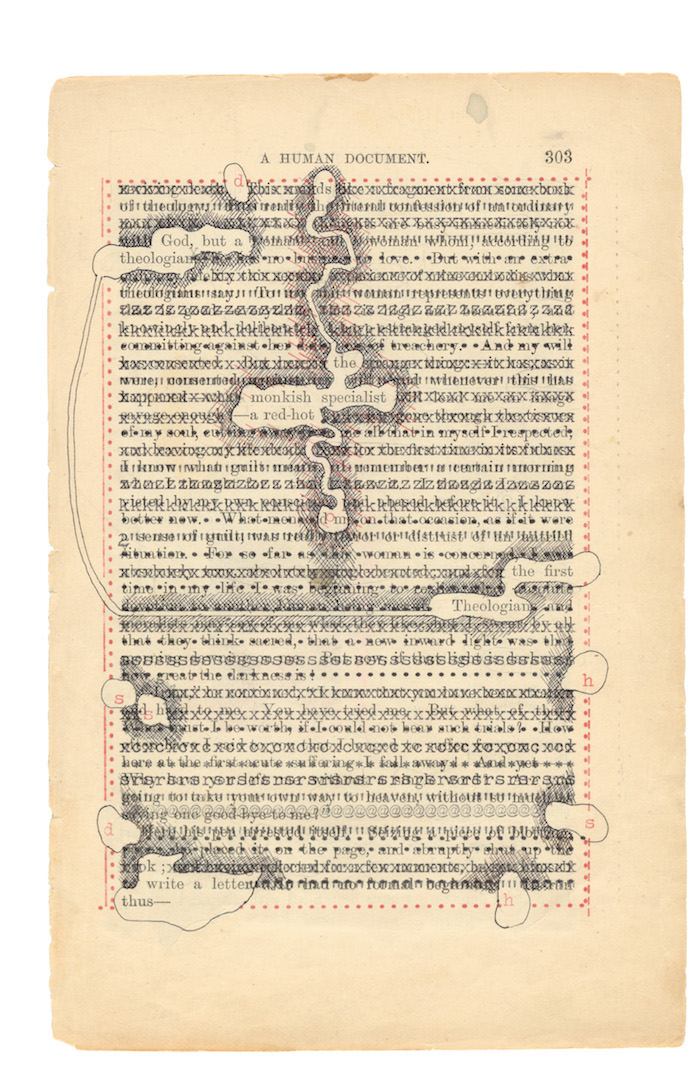

Tom Philips, a British artist whose work includes painting, filmmaking, musical composition (including opera), printing, and drawing (he is also a major collector of African art objects) has pushed the form further. In 1966, on a wager from the American artist R. B. Kitaj, he bought a Victorian novel, A Human Document, by W. H. Mallock at an antiques store in London. Ever since, he has been transforming the original words (a page appears below) of the book through ink, paint, and typewriting, using a mixture of chance and skill. As a result new texts come into being, revealing a parallel universe of hidden meanings.

Pages of A Humument, 1966–73, Tom Phillips; courtesy of The Sackner Archive of Concrete and Visual Poetry; © 2015 Tom Phillips

If typewriting has become a means for sophisticated art making, in filmmaking it signifies hard hitting journalistic authenticity, most famously in the title sequence of All the President’s Men. The titles start with a plain beige screen that is then explosively ruptured by a “J” striking the page. “June 1, 1972” is spelled out in maximum close-up and at top speed followed by a cut to footage of a triumphant Nixon entering Congress to rapturous applause after his Moscow summit. The foreshadowing is clear: the typewritten truth will take down the President.

Like LP’s, cassettes, and Super 8 film, the analogue appeal of the typewriter is highly seductive in the digital age. It symbolically carries an emotive countercurrent to the slickness of contemporary design, a throwback suggesting quirky individuality as opposed to corporate uniformity. But the fact of the matter is that the typewriter, and its characteristic typography, is now simply another style choice.

It’s now possible to download an app called the

Hanx Writer that transforms the screen of your iPad into a virtual typewriter, including the sound of the keys and the ding of the return carriage bell. It was created with the sponsorship of Tom Hanks, a self-professed typewriter connoisseur. The appeal of the app is partly visual (the industrial mid-century look of the typography and the vintage appeal of the carriage and keys), but it’s the re-creation of the sound of typing that seems to be its most compelling aspect. Hanks wrote an ode to the typewriter in the New York Times titled “I Am TOM. I Like to TYPE. Hear That?” In the hermetic world of the contemporary office, with most workers encased in their own private aural ecosystem, using the Hanx Writer would put the clickety-clack back into the writing soundscape, but it would probably be hard to hear with your Beats on.