February 6, 2018

Co-opting Design in the Name of Public Trust

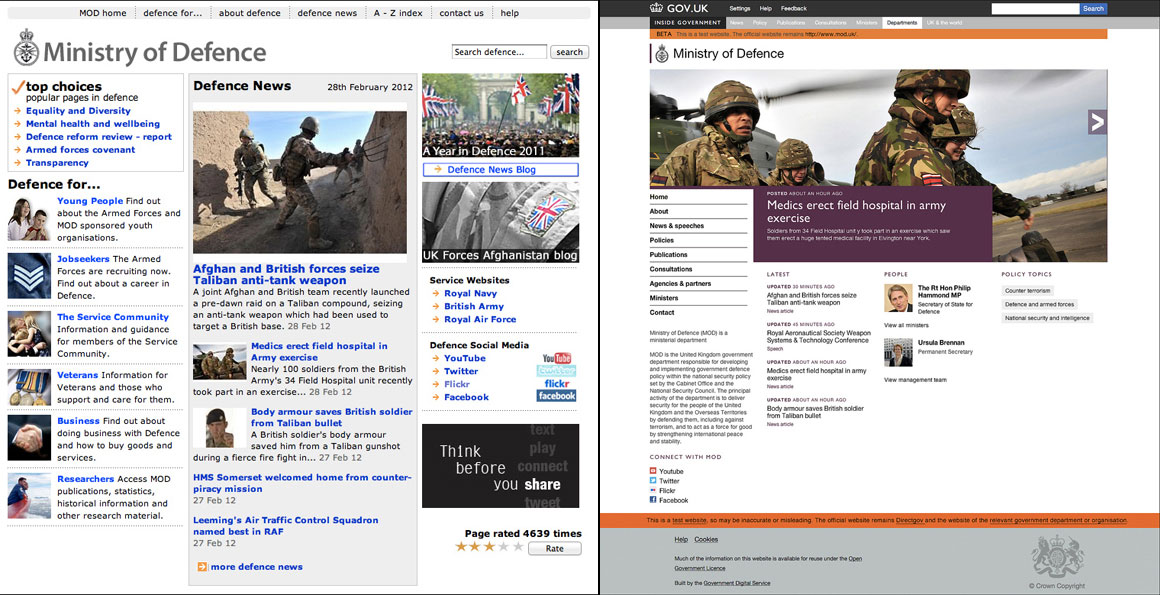

Ministry of Defence website before and after.

The U.K.’s Government Digital Service used strategic design to streamline its bureaucratic processes and services. Could it be the democratic system’s Hail Mary?

2011 was a particularly rocky year for Western democracy, with riots and protests erupting across the United States, United Kingdom, and mainland Europe. “Common to all of these stories,” wrote Dan Hill in his essay Dark Matter and Trojan Horses: A Strategic Design Vocabulary, “is this lack of faith in core systems. The systems in question could not be more fundamental, encompassing the economic foundations of Western development to the particular structures of governance and representation in all of the countries concerned, and essentially democracy itself.”

This absence of trust is just part of the fallout from the 2008 financial crisis that left the U.S. with some $4.6 trillion in bank bailouts and overall economic expense (initial funding known as the Troubled Asset Relief Program or TARP) as of 2009-2010, a number best contextualized by British author John Lanchester; “That number is bigger than the cost of the Marshall Plan, the Louisiana Purchase, the 1980s Savings and Loan crisis, the Korean War, the New Deal, the invasion of Iraq, the Vietnam War and the total cost of NASA including the moon landings, all added together—repeat, added together (and yes, the old figures are adjusted upwards for inflation).” The total cost has since become even greater.

Given these circumstances, it’s not surprising that the U.K. government—also straddled with debts of biblical proportions after its bailouts to banks RBS and Lloyds—became actively invested in the idea of governmental transparency and a more open democratic process. What is surprising is how much their development strategy would respond to Hill’s provocation that “today, these relations between the state, the market, and civil society are the design challenge. In particular, in the light of events over the last two decades, the social contract needs to be reformulated.”

What is surprising is how much GDS’ strategy responded to the provocation that “today, these relations between the state, the market, and civil society are the design challenge.”

Throughout 2011, the Cabinet Office (the body of ministers and civil servants directly supporting the Prime Minister’s creation and implementation of policy) engaged in a program of “Transforming Civil Service,” with the intention of closing the gap between policy creation and implementation, streamlining the bureaucratic process, and showing its workings publicly to rebuild trust. One of the stand-out successes of this initiative was the development of the Government Digital Service (GDS), through which the cabinet inadvertently began to explore the role of design within the public sector and civic life.

“Design has too often been deployed at the low value end of the product spectrum,” wrote Hill, “putting the lipstick on the pig. In doing this, design has failed to make the case for its core value, which is addressing genuinely meaningful, genuinely knotty problems by convincingly articulating and delivering alternative ways of being. Rethinking the pig altogether, rather than worrying about the shade of lipstick…”

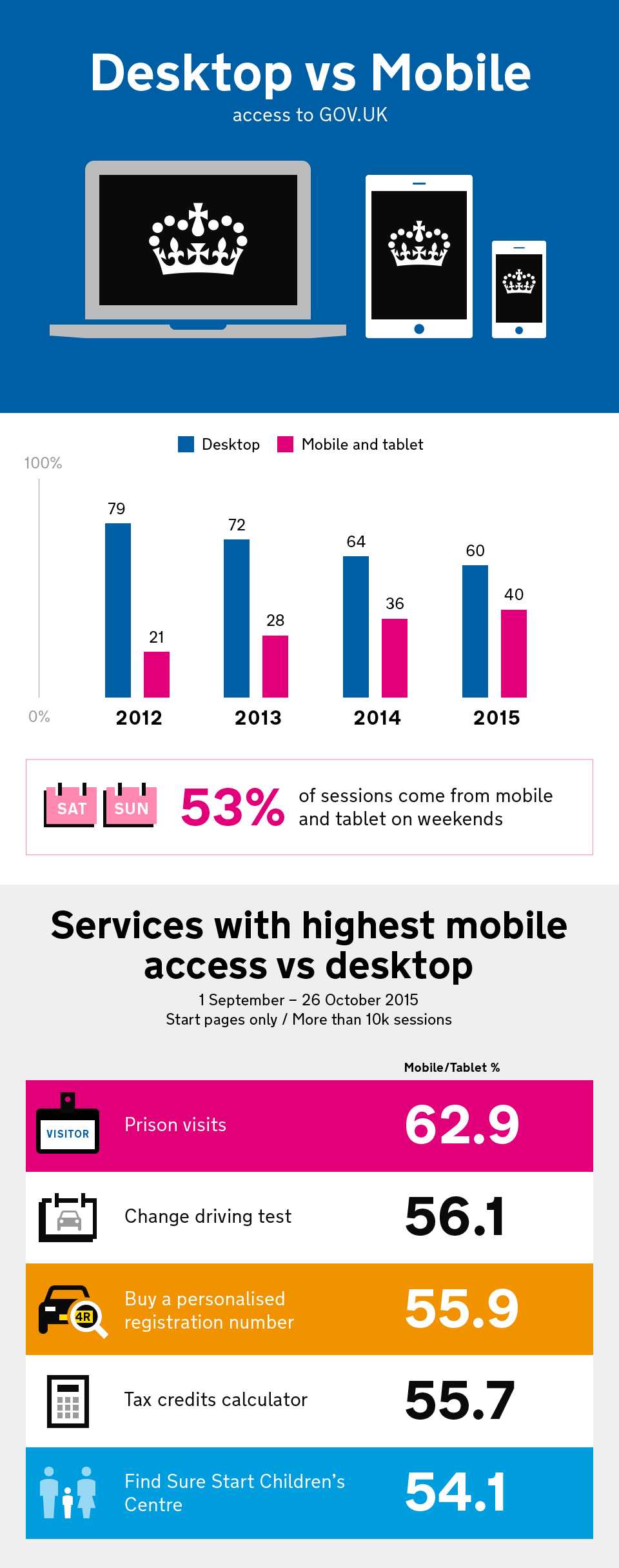

GOV.UK stats regarding desktop and mobile access as of 2015.

The GDS’s first project seemed to take Hill at his word, dispensing with the lipstick and completely rethinking the structure and implementation of public services delivered online—what Hill refers to as a “combination play of ICT culture, service design, and strategic design, moving back and forth from matter to meta, and earning a mandate for reform and redesign”.

Over 12 weeks GDS prototyped a single UK Government website that consolidated the content and objectives of a sprawling network of standalone sites—including the Ministry of Defence, Driver and Vehicle Licensing Agency (DVLA), and Companies House, and a new digital service for voter registration—many of which were no longer fit for use, and all for the reasonable sum of £261,000 ($373,000). Crucially it did this with an in-house team of designers (now civil servants) instead of outsourcing the task, enabling the department to iterate and develop GOV.UK in an open, agile way, producing prototypes and principles with lasting impact. Design, for the first time, became an integral part of government.

The benefit of this approach to governance and public service, argues Hill, is its allowance of “a way of moving forward in the first place… a prototype suggests a way of mitigating risk, through iterative approaches, while delivering ambitious change—it enables the platform and policy to develop structurally, finding a way to move free of the straitjacket of over-analysis and over-consultation.”

This is not the approach we’ve come to expect from Western democratic governments—in fact the notion of an iterative approach to democratic rule is anathema to the delineation and execution of manifestos in advance of and during a term of office. Would we elect a head of state who promised to give the role their best shot, but adapt and change should their proposed policies fail to deliver results? Not likely. “No politician,” says Philip Colligan, executive director of Nesta’s innovation lab, “was ever elected on a campaign that admitted they didn’t know the answer.”

And yet the strategic design approach adopted by the GDS, predicated on not having any answers, led to overwhelmingly positive feedback, active user engagement, and the development of trust, if not in government itself, then at least in the capability of the civil servants managing its day-to-day operations. “We get things out as quick as we can,” said then head of design at GDS, Ben Terrett. “Rather than just debate it in the office we want to see what people make of it.”

The strategic design approach adopted by the GDS, predicated on not having any answers, lead to overwhelmingly positive feedback, active user engagement, and the development of trust

By 2015, if statistics are a measure of success, what people made of it was overwhelmingly positive. In the three years between October 2012 and October 2015 GOV.UK had seen some 2 billion visits (roughly 103,800 visits per hour), making it one of the U.K.’s most popular websites. It’s busiest day saw a spike to 4 million users in advance of the 2015 general election, with some 750,000 people registering to vote within a 24-hour period. Streamlined design had improved access to democracy.

Concurrent to the development of their initial product, the GDS worked on ten principles to provide a neat blueprint for future projects—but many of them could equally be applied more generally to policy-making:

1. Start with needs

2. Do less

3. Design with data

4. Do the hard work to make it simple.

5. Iterate. Then iterate again.

6. Build for inclusion.

7. Understand context.

8. Build digital services, not websites.

9. Be consistent, not uniform.

10. Make things open: it makes things better.

These principles have since evolved into the 18 core tenets that make up the GDS’ Digital Service Standard, a manual for creating effective public facing digital platforms that place the user at the heart of the process. The Standard has been exported internationally, and digital government teams have been established along the same model in the U.S., Australia, and New Zealand.

It’s tempting to imagine how this methodology might benefit from a wider roll-out within government, with strategic design principles used to advance public involvement in political debate and the development of policy.

While undeniably a win for design within the democratic system, it’s tempting to imagine how this methodology might benefit from a wider roll-out within government, with strategic design principles used to prototype and iterate upon public healthcare models (where it’s available), and advance public involvement in political debate and the development of policy.

Pragmatically there are two main challenges to this idea; first that current governments in the U.K. and U.S. are against the idea of increasing the size of the state—a necessity for such a project. Second, that the systems and structures by which we are governed are simply too large and lumbering to be remade through prototyping and iteration.

The first problem is purely political, the second, thankfully, has already been addressed by Hill: “The hegemonic characteristics of such systems mean that we tend to ignore, or conveniently forget, that they have been designed; they have been imagined, articulated, stewarded into position.” So they can be stewarded out of position too.

GOV.UK stats regarding site usage and most-visited areas.

Observed

View all

Observed

By James Cartwright

Related Posts

Business

Courtney L. McCluney, PhD|Essays

Rest as reparations: reimagining how we invest in Black women entrepreneurs

Design Impact

Seher Anand|Essays

Food branding without borders: chai, culture, and the politics of packaging

Graphic Design

Sarah Gephart|Essays

A new alphabet for a shared lived experience

Arts + Culture

Nila Rezaei|Essays

“Dear mother, I made us a seat”: a Mother’s Day tribute to the women of Iran

Recent Posts

Minefields and maternity leave: why I fight a system that shuts out women and caregivers Candace Parker & Michael C. Bush on Purpose, Leadership and Meeting the MomentCourtney L. McCluney, PhD|Essays

Rest as reparations: reimagining how we invest in Black women entrepreneurs Food branding without borders: chai, culture, and the politics of packagingRelated Posts

Business

Courtney L. McCluney, PhD|Essays

Rest as reparations: reimagining how we invest in Black women entrepreneurs

Design Impact

Seher Anand|Essays

Food branding without borders: chai, culture, and the politics of packaging

Graphic Design

Sarah Gephart|Essays

A new alphabet for a shared lived experience

Arts + Culture

Nila Rezaei|Essays