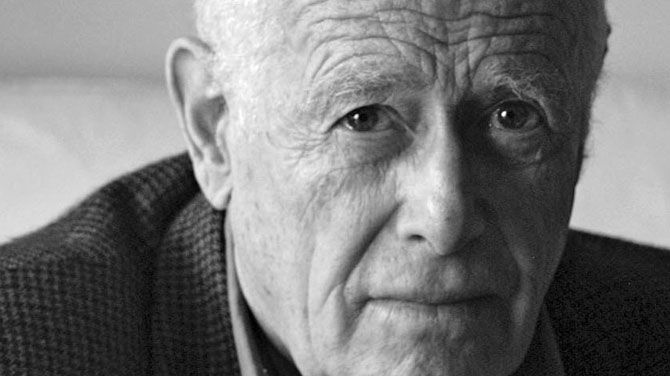

March 16, 2015

Cookie Tin Humanism

The parents of a childhood friend kept a cookie tin shaped like Michael Graves’ Humana building on their mantel. They treated this box as one might a piece of Pop sculpture and gave it pride of place other families would cede to baby pictures or a treasured heirloom. In Louisville, Kentucky, in the 1980s, the Humana building, which Time magazine would deem one of the best of the decade, was a source of civic pride and identity for the community. It was the kind of building you took out-of-town guests to see.

Clad in a rich palette of stone with a monumental loggia facing Main Street, the building is impressive without being intimidating. Inside the loggia, fountains splash, sending water cascading down large angled slabs. The company’s name is etched in stone and highlighted in gold leaf above the massive entrance. It has the kind of civic grandeur common among early twentieth-century banks. It conveys the sense that something important is happening within.

The expensive materials help elevate the building above some of its postmodern peers, with their clichéd cornices and classical order in-jokes, including Graves’ own Portland Building. For him, the language of postmodern architecture wasn’t political or even primarily aesthetic; it was personal. His compositions collage forms and images taken from memory, from historical sources, from the work of other architects, all filtered through his abstract vision. His use of classicism is never literal, but it gestures at something timeless. This is why his buildings were such a revelation in the late 1970s and early 1980s: they were the singular refutations of modernist orthodoxy, opening the door for others to break the rules as well.

Perhaps his closest fellow traveler was the enigmatic Italian architect Aldo Rossi, who incidentally also loved grids, pyramids, arcades, and teakettles. But while a moody gloom hangs over much of Rossi’s work, Graves’ works have a playful aspect. His delightful paintings and drawings—he was a great colorist—point to a sunnier, more Tuscan- or Provencal-inflected future.

This cheery pictorial tendency occasionally veered into cheap and cartoonish territory. Sometimes the cartoonishness was intentional, as in his silly but sly hotels for Disney. But in general, people of many ages, backgrounds, and tastes relate to his buildings. As postmodernism fell out of fashion in architecture and many of his contemporaries moved toward purer historicism (Robert A. M. Stern, for example) or neo-Modernism, Graves stuck to his vision. He continued to attract clients both in the US and abroad.

Given his capacity as a crowd-pleaser, it is not surprising then, that Graves became a star industrial designer, creating both high-end products for Alessi and Steuben and mass-market objects for Target and JC Penney. In the process, he arguably became America’s second most famous architect after Frank Gehry.

A little alarm clock he designed for Target sits on my bedside, as it has for more than a decade. And though its cheerful face is made of plastic, the clock has a satisfying and necessary weight, allowing it to survive its many clumsy encounters with my sleepy hands. In total his firm has brought over 2000 products to market. His Alessi teakettle is a contemporary classic.

The humanism that runs throughout Graves’ architecture and objects came even more to the fore in the surprising third act of his career. Paralyzed from the waist down after a spinal infection in 2003, he turned to his experience as an industrial designer in order to create products and equipment that would improve health and safety for the elderly, the disabled, and the sick. He also designed health facilities and housing for veterans.

While he began his career as member of the avant-garde New York Five, his radicalism was ultimately his populism: he strove to use his personal vision to try to reach for the universal and timeless, to conceive of an architecture that improved both civic and domestic life, to be an architect you could live with.

Observed

View all

Observed

By Alan G. Brake

Recent Posts

Candace Parker & Michael C. Bush on Purpose, Leadership and Meeting the MomentCourtney L. McCluney, PhD|Essays

Rest as reparations: reimagining how we invest in Black women entrepreneurs Food branding without borders: chai, culture, and the politics of packaging Why scaling back on equity is more than risky — it’s economically irresponsible