Chris Pullman|Dan Friedman, Essays

May 12, 2015

Dan Friedman, Radical Modernist, Part 2

On Thursday the AIGA will award Dan Friedman, among others, the AIGA Medal. This week we publish a remembrance of Dan by his friend Christopher Pullman. Read Part 1 here.

When I graduated from the Yale MFA design program in 1966 I was invited to join the faculty, a role I have fulfilled ever since. In January 1970, on Armin Hofmann’s recommendation, Dan Friedman arrived at Yale, fresh from his studies in Basel, to teach. He was a strange, shy character in a tight blue suit, gray shirt, and black tie with a shock of fuzzy hair and a peculiar, halting speech pattern.

At Yale Dan encountered an impressive home team: the already well known Paul Rand; Herbert Matter, a quiet and intuitive designer and photographer who emigrated from Switzerland in the 1930s to help establish the tenets of European modernism in America; Bradbury Thompson, the dean of magazine designers; Norman Ives, a graduate of the first Yale Design Class in 1950 whose own formal aesthetic informed his teaching; Walker Evans, a wry and literate character whose work in the ’30s transformed American photography; and Alvin Eisenman, whose encyclopedic interest and uncanny sense of how the discipline was changing had guided the graphic design program at Yale since its inception.

As Armin’s protégé, Dan had some credibility with this crowd, but his youth and conviction about his ideas of how and what to teach didn’t sit well with some of the old guard. I was the junior faculty member and while I sort of liked Dan, his sense of superiority irked me. I would listen to his well-founded notions of how to run a school, feeling the underlying condemnation of my own training, which, measured against the rigorous, highly refined philosophy of Basel, appeared haphazard and defective. His certitude about my professional deficiencies undermined my own confidence as a teacher and made me wary of his friendship.

Dan arrived at a chaotic time: a year after Bobby Kennedy and Martin Luther King were gunned down. Berkeley, Columbia, and Harvard had been shut down by student strikes protesting Vietnam and civil rights abuses. All the while, Yale was in the middle of its own crisis. The spring before Dan arrived, the Art and Architecture school mysteriously went up in flames late one night; the local paper reported arson. The next spring National Guard troops were staked out across the street from the art school, anticipating a riot.

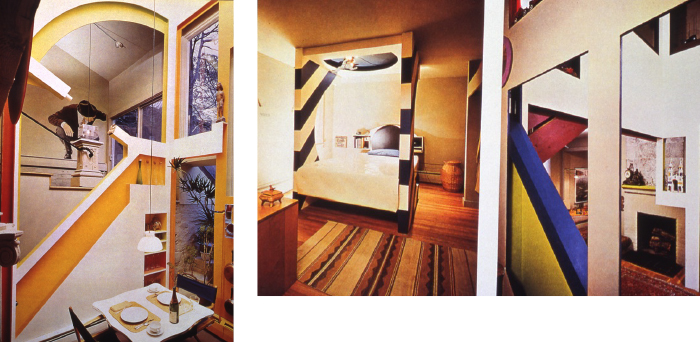

In his book, Dan writes that although the country was in turmoil, “it was also a time of liberation, idealism, and experimentation—a time considered by many to be a cultural turning point.” And indeed it was. Architect Robert Venturi had challenged the core tenets of Modernism with his pronouncement, “Less is a Bore.” The incoming Dean of Architecture at Yale was Charles Moore, an idiosyncratic and high-spirited fellow who agreed with Venturi’s slogan. His experiments on his own house in New Haven opened up a whole new vocabulary of graphic, color, and spatial ideas.

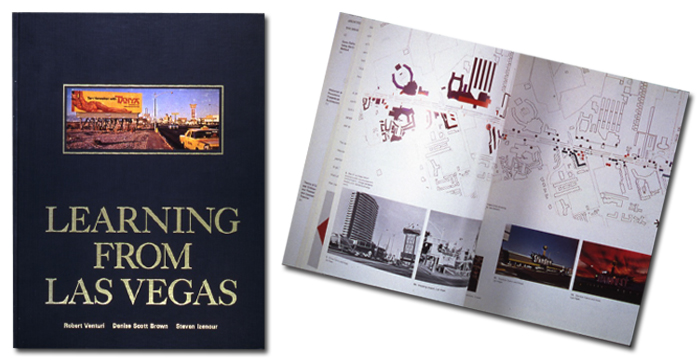

Venturi was invited to Yale. He put together a groundbreaking multidisciplinary studio called Learning From Las Vegas, which saw the crass, bizarre structures of the Vegas strip as an exhilarating and legitimate architectural response to place (and which resulted in the controversial, but now revered, 1971 book of the same name). The study opened the profession’s eyes to the vitality of vernacular forms and indigenous structures and encouraged designers, in Dan’s words, “to express rather than exclude the dumb and fractured context of the real world.”

All this was part of the larger intellectual and formal phenomena called Postmodernism that would eventually spread throughout academe. In his book, Dan reflected on how all these influences affected him:

“I found an analogue to these issues in my own field of visual communications. I was attracted to the spareness, abstraction and Zen-like purity characteristic of orthodox modernism. But I was also intrigued by more hidden complexities; by the more vernacular; by working against the rigidity, boredom, and exclusiveness that were increasingly associated with modernism. Most important, I was not prepared to see these points of view as inherently contradictory.”

“I began to think about a reconceptualized modernism,” he continued, “more radical in that it would not only accommodate order along with chaos but would embrace a variety of other conditions no longer paired as dichotomies.”

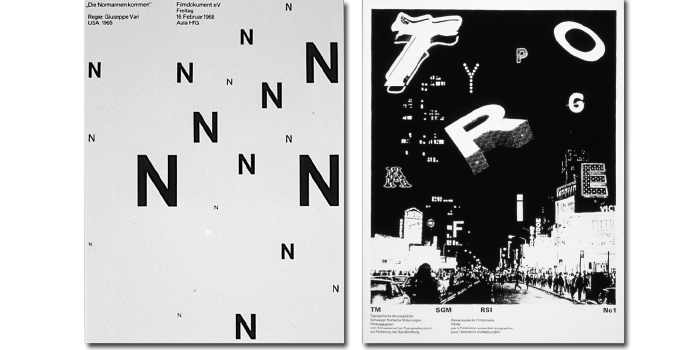

Dan came to Yale loaded with two different design influences: the austere, reductive, elegant restraint typical of his experiences at Ulm: Ruder juxtaposed with the playful, intuitive troublemaker side encouraged by Weingart, and inherent in Dan’s own persona.

This dichotomy would fascinate him throughout his career as a teacher and a practitioner, and fuel a continuous process of reconciliation between his deep faith in the progressive aspirations of modernism and his sense that this philosophy had to evolve to account for the chaotic, unpredictable, dangerous, and ridiculous reality of the world he inhabited.

Part 3 tomorrow

Observed

View all

Observed

By Chris Pullman

Related Posts

Business

Courtney L. McCluney, PhD|Essays

Rest as reparations: reimagining how we invest in Black women entrepreneurs

Design Impact

Seher Anand|Essays

Food branding without borders: chai, culture, and the politics of packaging

Graphic Design

Sarah Gephart|Essays

A new alphabet for a shared lived experience

Arts + Culture

Nila Rezaei|Essays

“Dear mother, I made us a seat”: a Mother’s Day tribute to the women of Iran

Recent Posts

Courtney L. McCluney, PhD|Essays

Rest as reparations: reimagining how we invest in Black women entrepreneurs Food branding without borders: chai, culture, and the politics of packaging Why scaling back on equity is more than risky — it’s economically irresponsible Beauty queenpin: ‘Deli Boys’ makeup head Nesrin Ismail on cosmetics as masks and mirrorsRelated Posts

Business

Courtney L. McCluney, PhD|Essays

Rest as reparations: reimagining how we invest in Black women entrepreneurs

Design Impact

Seher Anand|Essays

Food branding without borders: chai, culture, and the politics of packaging

Graphic Design

Sarah Gephart|Essays

A new alphabet for a shared lived experience

Arts + Culture

Nila Rezaei|Essays

Chris Pullman served as vice president of design for WGBH for 35 years. Viewers of PBS will recognize his work in the opening title sequences of “Masterpiece Theatre” and “Antiques Roadshow” and the WGBH animated on-air signature.

Chris Pullman served as vice president of design for WGBH for 35 years. Viewers of PBS will recognize his work in the opening title sequences of “Masterpiece Theatre” and “Antiques Roadshow” and the WGBH animated on-air signature.