November 17, 2010

Dan Wood

Dan Wood and Amale Andraos founded WORK Architecture Company in New York in 2003, after meeting at Rem Koolhaas’s Office for Metropolitan Architecture, where both worked for a number of years. Since then, they have operated their practice as a New York–style think tank, designing a headquarters for Diane von Furstenberg, a multi-level apartment for her fellow fashion designer Lela Rose and a new public library for Kew Gardens Hills in Queens; teaching at Princeton; publishing their research on 49 Cities, also a 2009 exhibition at the Storefront for Art and Architecture. Current work also includes the extension of the Clark Art Institute at Mass MoCA and a new Children’s Museum for the Arts. In addition, their entry for the redesign of Hua Qiang Bei Road, Shenzhen, was recently awarded first place in an international competition.

Since 2003, their research and teaching have focused on paired questions about ecology and urbanism, food and design. They first explored these issues in three dimensions with their winning entry for the MoMA/PS1 Young Architects Program in 2008: PF1, or “Public Farm 1,” a reinvention of the summer pavilion as a working farm made of cardboard tubes. The process of putting that installation together is the subject of the small book Above the Pavement, The Farm! Architecture & Agriculture at PF1, published this year by Princeton Architectural Press.

As a result of that project, they were hired to design the first Edible Schoolyard New York with Alice Waters’ Chez Panisse Foundation. The first phase of the schoolyard opened in October at P.S. 216 in Gravesend, Brooklyn. WORKac’s more architecturally ambitious kitchen classroom and mobile greenhouse will go into construction in 2011.

Dan Wood spoke with Alexandra Lange on September 23, 2010.

Alexandra Lange:

Why the farm for PS1 in 2008?

Dan Wood:

We were teaching at Princeton about ecology and urbanism, trying to invent it as a subject because at that point, seven years ago, there wasn’t anyone talking about it and there weren’t many examples. We realized in studying the urbanism part there was a whole different way of looking at urban projects that already existed through an ecological lens. We could go back and re-read projects and see how people throughout history have looked at the city and nature. That was the start of our 49 Cities project. We looked at density and floor area ratio and population numbers. The idea was to bleed them of any social or political outlook and to consider them as if they were real proposals.

The most interesting was to look at the relationship between green space and the city. Most of the early examples, up to the Garden City, from the Roman city to Tony Garnier to the phalanstère, always had a relationship between agricultural production and the cities they were proposing. For us, urban farming became a way of talking about the sustainable city.

.jpg)

AL: So you figured out that urban farming had been there all along.

DW: Then we found Carolyn Steel’s book Hungry City. Many cities, like London, are completely shaped by getting food in. There are neighborhoods for chickens and ducks and neighborhoods for cows. The streets are organized as markets. For us, it was a way of talking about the ecologic city.

At PS1, our first moment was realizing that all they wanted was shade, seating and water. We were going to end up building it and paying for it so we could do whatever we wanted. Since we were looking at all these visionary projects that never got built, we were wondering if we could build a visionary project. A little slice of what a future city could look like or act like. That gave rise to the farm.

We didn’t know anything about farming, or gardening, or dirt. For us what was important was to look at ways that the land could be lifted. Not necessarily stacking it and using artificial sunlight, but to put urban program underneath the land so you have two worlds co-existing.

We were really interested in the Superstudio images of things cutting through the city. Our first idea was a plane of farm passing over that would create the shade. That’s the ’60s approach. We realized it was very heavy — all those plants — and no one could see the plants, which defeated the purpose. We bent it, so half sits on the ground, and cut the weight by half. Weight is the issue.

DW: Weight is the foil. We are always working against weight. Bent, it is a much more nuanced shape and it also created all these different spaces beneath it. For us it became this dialogue about 40 years after 1968. In 1968, it was all or nothing. For Gen X, it is just all.

It was the right moment: Ecology was starting to become important, urban farming was starting to be really interesting to a lot of people, and people still had money to throw around.

AL: So you had more money to work with than some subsequent winners.

DW: During the competition we contacted irrigation people, solar-panel people, and got them to commit. When we presented our budget to MoMA we said we are going to get all of these things. It was still over budget, but…

AL: How else did you keep the budget down?

DW: If you ask a bunch of strangers to help you build an architectural folly, you are going to get architecture students. But if you ask a bunch of strangers to plant something you get ten times more than you ever wanted. Gardening is really exciting for people and creates a whole different kind of community spirit.

That’s one of the things we try to get across in the PF1 book. It started out as a project of ideas. It ended up a project about people. Everybody donated their thinking. That New York Times article came out and the next day Michael Grady Robertson, from the Queens County Farm, contacted us and said, “I am an organic farmer and I am in the city. Give me a call.” He was in the process of transforming that into a model sustainable farm. Two thirds of our plants were grown there. [He has since left to start his own farm in Red Hook, NY.]

Amale Andraos and Dan Wood at PF1, their public farm installation at PS1

Amale Andraos and Dan Wood at PF1, their public farm installation at PS1

We said in the article, “We would like there to be a farmers’ market.” The Council on the Environment NYC (now GrowNYC) called us and said, “We’ll put one there, no problem.” They did all the water reclamation, which we hadn’t thought about. They said, “You should collect rainwater.” And we said, “How do we do that?” Well, the roofs.

DW: When we presented our studio project to the kids at Princeton this year, Amale started out talking about the Coolhaus truck. It adds this public aspect to L.A.

These people will all call you. Fritz Haeg used to be an architect and now he does gardening. In the architecture world, if you have two people who have the same idea, they are not going to say, “Here’s this computer program that can help you make those shapes.” But he immediately said, “Use this, do this.”

PF 1 led to Edible Schoolyard. We call it PF2. John Lyons, the president of production at Focus Features, is on the Chez Panisse board. He always wanted to do an Edible Schoolyard, New York version. He went to PS1 at the end of the summer of 2008 and he called us.

Rendering of Edible Schoolyard New York building and greenhouse

Rendering of Edible Schoolyard New York building and greenhouse

AL: What’s the status of the Edible Schoolyard New York?

DW: The kitchen classroom is Phase 2 because the plans have to go through the School Construction Authority and that takes forever. But the garden is in, and we built this ramada, a semi-enclosed structure, and painted a container shed with the same pattern we are doing on the building. It is our homage to Venturi, pixellated. It is a scale pattern and each tile will be a pixel. [Edible Schoolyard New York opened at Brooklyn’s P.S. 216 on October 13. —Eds.]

AL: Have previous Edible Schoolyards been so designed?

We went out to Berkeley and made a list of what we thought were the most important elements of the Edible Schoolyard there. The ramada is central to the mission; that’s why it got built first. We took pictures inside the kitchen classroom and tried to channel some of the iconic elements — while making it new, adapting it for the New York climate and adding our personal touch.

We kept the checkered tablecloths and the cubbies. These are the same clocks they have there. Alice said she thinks this project takes Edible Schoolyard to the next level and gives it more legitimacy. It is not this semi-ad-hoc or organic project, but something that can be changed.

AL: It sounds like a prototype.

DW: That’s the other thing about New York: you can’t just focus on one school. There’s political pressure: what about all the other schools? This is now an academy model, and [City Council President] Christine Quinn has committed that if we do this one she’ll get the money for the other four boroughs. Each borough will have one main classroom, and other schools will come there for training and have their own little gardens. P.S. 216 will have a staff of five: two kitchen staff, two garden staff and one manager. Those people will be available to advise the other schools.

AL: I am sure you have read some of the critiques of the Edible Schoolyard.

DW: Well, the one famous one [by Caitlin Flanagan in The Atlantic]. Alice is always open to critique because for her it is the one perfect tomato. And not everyone can have the perfect tomato. That can come off the wrong way. But why not have everyone have the best? My father is the head of the Clinton HIV/AIDS program and that is their philosophy, too: give the poorest people the best drugs.

AL: Designers want to work with food because they see that food is a language that more people understand and like. What’s the value added of the design?

DW: The building can function off grid in the middle of the city. It is not only producing food but it is also producing its own power and collecting its own rainwater. We are going to try running the rainwater pipes through the compost to provide hot water, which hasn’t been done much before. We are going to try to use solar heating or a biomass burner to heat the space.

We are also utilizing design specifically to adapt Edible Schoolyard to the New York City climate. We also have a space problem in New York. This is less than half the size of Berkeley, maybe a third. What we discovered working with our network from PS1 was you have to extend the growing season. Kids are in school in the winter and late fall and early spring when you can’t grow outdoors.

Everyone pointed us toward this guy Eliot Coleman. He is able to grow fresh vegetables in all four seasons in Maine through a system of movable greenhouses. You are planting in the soil and just heating it enough to be able to grow cold-weather crops all through the winter. The greenhouse is on tracks so in summer you move it away, plow under the plants you have grown in the winter, and plant an entirely new crop on the same ground. Also a very rich growing medium.

He just pushes the things to one side because he has a lot of space. We don’t have a lot of space so the whole shape of the building is designed around this very large mobile greenhouse. In the winter it is this growing oasis; you are still growing in the ground. Then in summer the whole thing slides over the roof of the kitchen classroom. This also creates a new tradition. When the weather starts to get warm in the spring, the kids get together and push the greenhouse out of the way. I feel like design is creating something interesting, dynamic and different but also addressing a very practical issue.

Concept for Edible Schoolyard New York’s seasonal mobile greenhouse

Concept for Edible Schoolyard New York’s seasonal mobile greenhouse

AL: If it is built elsewhere will it essentially be the same building? That would make it go more quickly through the bureaucracy, right?

DW: This one will be expensive, but the next ones will be cheaper. This one will be more privately funded, but the city will be able to pay for the other ones. We are looking to prefabricate elements to save time and money and also to cut down on the bureaucracy and time on site. But it has been going very smoothly at P.S. 216.

DW: First, there are the stacked farms, which can’t work without a ton of energy or some kind of logical locale. Dubai or Tokyo could be interesting to try them out. Tokyo because it is on an island, not much land, a lot of people. Dubai, you can’t grow on the ground anyway. But in the U.S. we are a food exporter so I feel it is a solution for a question nobody asked.

We have an idea we call “rurbalization.” There is a famous diagram by Ebenezer Howard of Town and Country. The Town is polluted but the Country is boring, no social life, very poor. He asked, The People, Where Would They Go? We took that diagram and translated it to today, to the City, which is doing pretty well, and the Countryside which is doing badly because industrial farming is bad for the food system and bad for the environment. Town-Country has become the suburbs, the worst of both worlds. The idea is to go back before there was Town-Country and eliminate the suburbs. Have cities that become more local, communal, collaborative and green. Reorganize what used to be the suburbs and the rural into a better food system. We made a movie exploring this idea called New Ark. We chose New Jersey as our example, which seems like the suburbs but it is very dense, there’s all that transportation, and still it is very green.

WORKac’s adaptation of Ebenezer Howard’s diagram mapping the pros and cons of different living environments

WORKac’s adaptation of Ebenezer Howard’s diagram mapping the pros and cons of different living environments

AL: Looking around at your models there is a certain back-to-the-1970s look about things, which makes me think about the Ford Foundation. Many people love the Ford Foundation but of course that landscape is totally unsustainable. How do you turn that into a good landscape?

DW: All the 1970s gardens have roofs! We were commissioned to design a skyscraper for the future by the Alliance for Downtown New York as part of ARO’s master plan for Greenwich South. The site was in shadow from all these other buildings, so we cantilevered it out over West Street so that everyone has a roof and can get some sunlight. It is a spiraling set of volumes with ecosystems on the roof and a central core of environmental services called the “Plug Out.”

“Plug Out” building concept designed for Architectural Research Office’s master plan for Greenwich South in Manhattan, a project commissioned by the Alliance for Downtown New York

“Plug Out” building concept designed for Architectural Research Office’s master plan for Greenwich South in Manhattan, a project commissioned by the Alliance for Downtown New York

We were really influenced by Michael Pollan, especially the chapter on Joel Salatin, owner of Polyface Farm. The farm is a good metaphor for the city, because it is a natural environment in one sense but it is also completely manmade. If the stewardship is good enough, the impact of man can make the land more productive and more sustainable than it would be on its own. By creating an ecosystem man’s impact can help land be better. There must be a way to do that with a city. You use all the people and all the buildings, foodways from the restaurants, the sewer system that’s already here, all the rain, all the rooftops to make the city work like a farm.

Observed

View all

Observed

By Alexandra Lange

Related Posts

Design Impact

Alexis Haut|Education

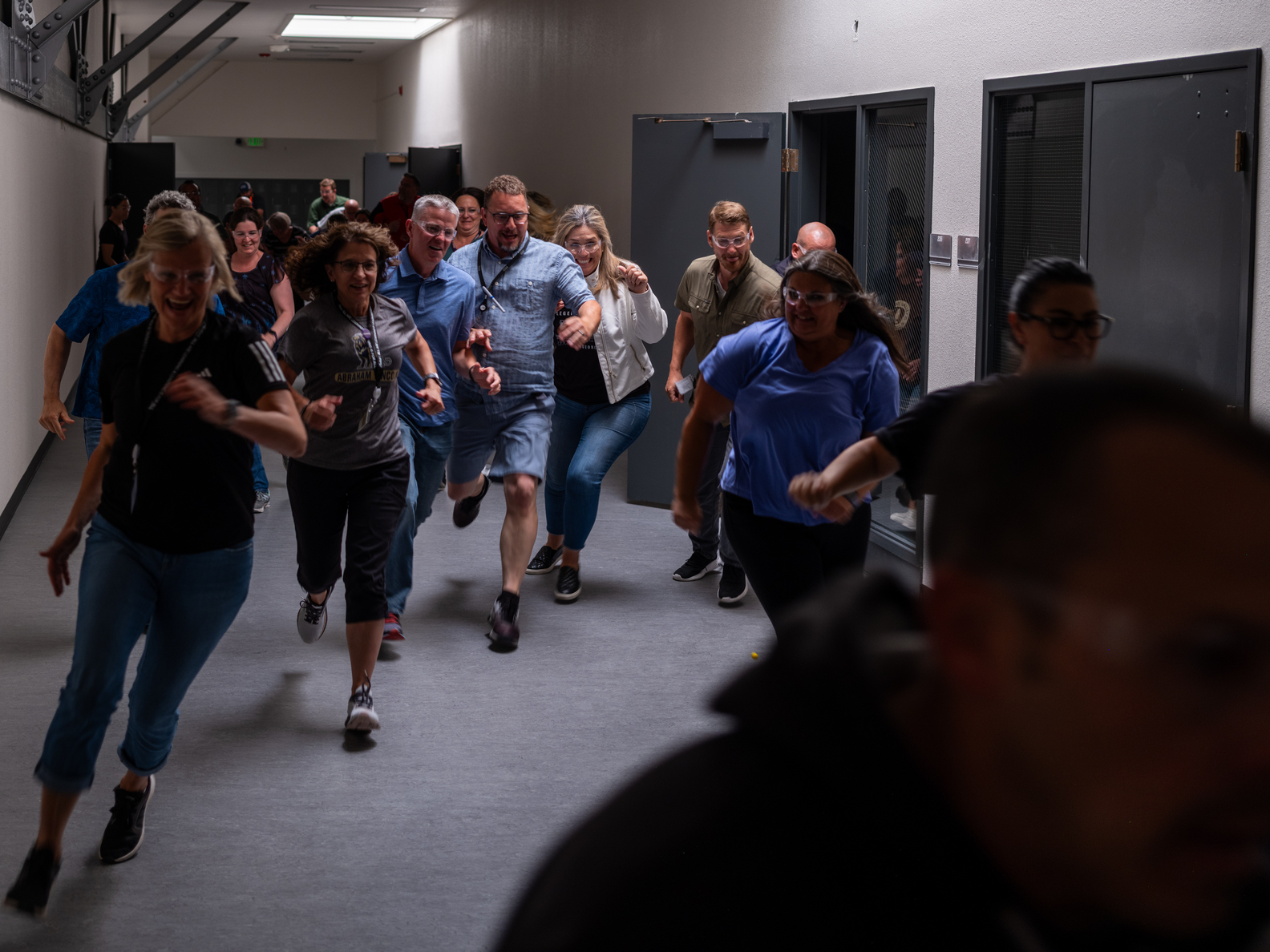

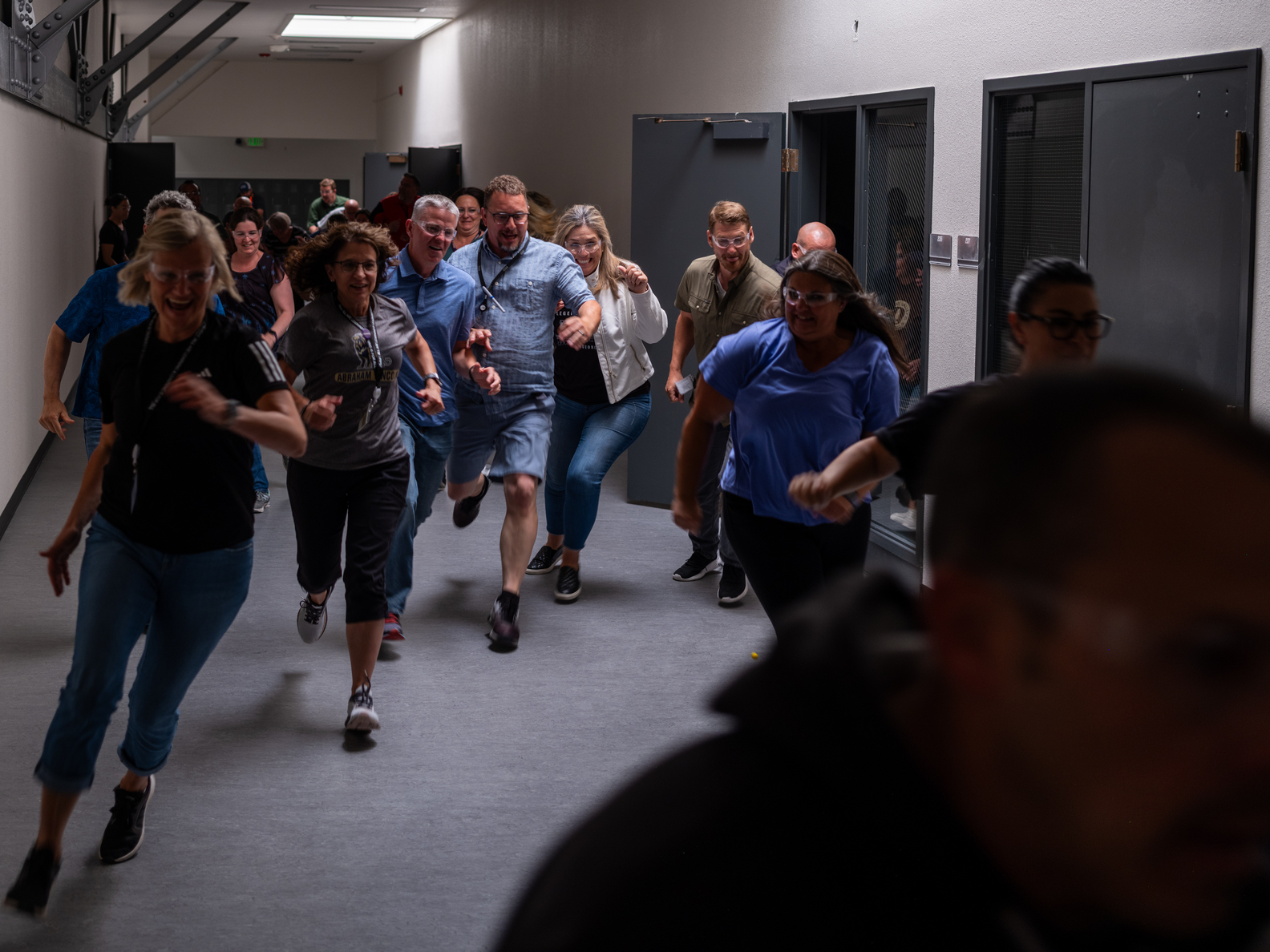

‘Thoughts & Prayers’ & bulletproof desks: Jessica Dimmock and Zackary Canepari on filming the active shooter preparedness industry

Design Juice

Ellen McGirt|Interviews

Making ‘change’ the product: Phil Gilbert on transforming IBM from the inside out

Arts + Culture

Alexis Haut|Interviews

How production designer Grace Yun turned domestic spaces into horror in ‘Hereditary’ and heartache in ‘Past Lives’

Arts + Culture

Alexis Haut|Interviews

Beauty queenpin: ‘Deli Boys’ makeup head Nesrin Ismail on cosmetics as masks and mirrors

Related Posts

Design Impact

Alexis Haut|Education

‘Thoughts & Prayers’ & bulletproof desks: Jessica Dimmock and Zackary Canepari on filming the active shooter preparedness industry

Design Juice

Ellen McGirt|Interviews

Making ‘change’ the product: Phil Gilbert on transforming IBM from the inside out

Arts + Culture

Alexis Haut|Interviews

How production designer Grace Yun turned domestic spaces into horror in ‘Hereditary’ and heartache in ‘Past Lives’

Arts + Culture

Alexis Haut|Interviews

Alexandra Lange is an architecture critic and author, and the 2025 Pulitzer Prize winner for Criticism, awarded for her work as a contributing writer for Bloomberg CityLab. She is currently the architecture critic for Curbed and has written extensively for Design Observer, Architect, New York Magazine, and The New York Times. Lange holds a PhD in 20th-century architecture history from New York University. Her writing often explores the intersection of architecture, urban planning, and design, with a focus on how the built environment shapes everyday life. She is also a recipient of the Steven Heller Prize for Cultural Commentary from AIGA, an honor she shares with Design Observer’s Editor-in-Chief,

Alexandra Lange is an architecture critic and author, and the 2025 Pulitzer Prize winner for Criticism, awarded for her work as a contributing writer for Bloomberg CityLab. She is currently the architecture critic for Curbed and has written extensively for Design Observer, Architect, New York Magazine, and The New York Times. Lange holds a PhD in 20th-century architecture history from New York University. Her writing often explores the intersection of architecture, urban planning, and design, with a focus on how the built environment shapes everyday life. She is also a recipient of the Steven Heller Prize for Cultural Commentary from AIGA, an honor she shares with Design Observer’s Editor-in-Chief,