September 22, 2010

Degrees of Temporary

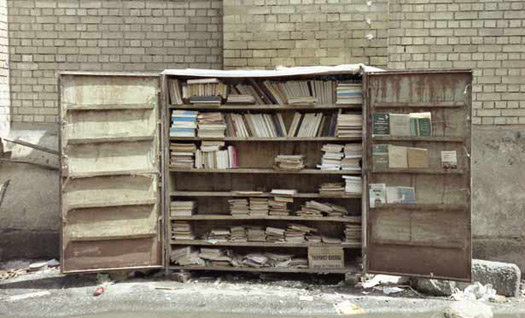

A Ticket to Baghdad, ongoing visual project launched with 10th International Photography Festival, Aleppo, Syria, 2006. All images courtesy aMAZElab

Jade Dressler: I found aMAZElab in a Google search for green islands in urban areas. You’ve put an apple orchard in Milan’s Garibaldi Railway station, as an urban intervention. Tell us about aMAZElab; exactly what is it?

Claudia Zanfi: AMAZElab is a nonprofit organization, founded by GianMaria Conti and myself, that focuses on cultural production and social engineering. Mobility, migration, memory, borders, new geographies, the Mediterranean area and the Middle East, the public sphere and sustainability are our areas of interest. We collaborate with national and international institutions to explore territorial and social change.

JD: Your projects are based in physical spaces, yet you define place as something beyond land and culture. Such works as A Ticket to Baghdad, for which you’ve interviewed young Iraqi artists about their aspirations, and Going Public, an annual exhibition of international artworks that often took geography, conflict and identity as their themes, are described as “anthropologies of day-to-day life.” How do you use locations as platforms that extend into broader, more nebulous realms?

CZ: Some of the most conflicted areas where we work also seem to be the most creative. For example, there is a very intriguing art community in Beirut; an active cultural reality in Nicosia; writers, musicians and filmmakers in Tangiers; a lively art scene in Jerusalem. The city and everyday social relations are central to our analysis of such pressing topics as the apparent mobility and flexibility of borders. International debates, geopolitical considerations and the mass media have a strong bearing on the new notion of “maps,” whose elusive boundaries are often impossible to trace. These maps constitute an abstract idea more than a possible or probable depiction in an atlas. Cities today are lands of migration, transit, passage — all of them degrees of “temporary.” Such “states of exception” (in the phrase of the philosopher Giorgio Agamben) create the basis for discussion as well as socio-artistic research and experiments.

Mobile bookshop, Baghdad, 2002

JD: What is your definition of networked cultures, given your projects in this realm?

CZ: From the beginning (2010 is our tenth anniversary!) we’ve been developing a network for creative production, reflection and cultural exchange in interdisciplinary areas. We have called this MAST (Museo di Arte Sociale e Territoriale) a kind of new museum without walls or a fixed location.

JD: Can you speak about how culture and art currently intersect in specific cities and territories? For example, tell us about the Memory Box. I imagine it could be like an urn found by a futuristic culture.

CZ: The Memory Box is a mobile device for “emergency zones.” It functions as a public kiosk for sound installations, lectures and performances. A cultural antenna, it has been activated along sensitive border areas such as Weimar, Germany and Larisa, near Greece, and works by comparing history, or the official and political version of events, with stories told by people who have lived those events. After being located in a specific place, the Memory Box becomes a link between present and future stories, recollections and identities. In this way, it records not only experiences, but also visions and hopes.

Temporary residence on the Green Line of the divided city of Nicosia, Cyprus, 2006–2007, featured in the 2008 exhibition “Post-It City” at the Centre de Cultura Contemporània de Barcelona

We placed a Memory Box constructed from bus parts in Nicosia, Cyprus, a city split between Turkey and Greece — the world’s last divided capital. People entered into the Box for about 5 to 15 minutes and talked freely about their emotions. I cried observing this, and I wasn’t the only one. It became something like a Wim Wenders way of narration, a history told through the camera and supplemented by footage from road movies. Our second stop was in Larisa. It is a super-peculiar, not-very-well-known place — a hub for the most alternative groups and activities: trade unions, student movements, many thinkers and writers.

Dutch architect Ton Matton’s rendering of an orchard later installed in Garibaldi Station for aMAZElab’s eighth Green Island event, Milan, 2008

JD: What was the goal of Green Island, your railway station project?

CZ: Green Island was conceived for 2002 Milan Design Week at the city’s Garibaldi Railway Station and has continued every year since. It’s about rethinking public space, and not only in public gardens or parks. We wanted to create small places with intention, such as the Musée du Quai Branly in Paris, where Jean Nouvel worked with gardeners and artists to project a living wall as a green public area.

Green Island projects are modular and can be adapted to different contexts. By exhibiting not in a gallery but in a railway station, through which 25 million commuters “migrate” every year, we emphasize our themes of collectivity and mobility.

The project also encourages interdisciplinary dialogue. Many international architects, artists and designers have contributed to Green Island since it began: Ton Matton, Atelier Le Balto, Lois & Franziska Weinberger, Critical Garden, Medusa Group, A12, Andrea Branzi….I find the Venice Architecture Biennale much more thought-provoking than the Venice Art Bienniel, because architects have long embraced the idea of multiple disciplines coming together for discourse.

JD: What are your favorite urban interventions?

CZ: I like the ephemeral monuments that Thomas Hirschhorn has dedicated to Deleuze, Spinoza, Bataille and Gramsci. What makes those installations special is the participatory process that brought them into being and the re-articulation of the readymade from a sculptural object to one of mere spatial demarcation. To look at urban interventions, we think that art can be like a seed: it works to stimulate and activate creative processes, which become platforms for social debates.

JD: Will you be participating in Expo 2015 in Milan, whose theme is “Feeding the Planet, Energy for Life”?

CZ: Expo 2015 can be a big chance for Milano. We believe that it’s time to rethink the very blueprint of the city: new environments and new social figures, residents, students, craftsmen, nonprofit organizations, creative studios. In the city that never stands still, in which so many open and unpredictable situations are created, in a constant process of evolution, distortion and transformation, green spaces are no longer to be looked upon as objects, but rather as elements of great intensity.

JD: How do you see urbanism in the future? What would be your dream project?

CZ: I see a permanent vegetable garden in the center of Milano created by artists and agronomists. The tools for change today are as simple and powerful as a handful of seeds or a Twitter post, and the glue is thankfully people hungry for change through artful, connected and beautifully designed experiences. A biological and technically mixed Utopia? Perhaps. I’m glad it’s here.

Observed

View all

Observed

By Jade Dressler

Related Posts

Arts + Culture

Alexis Haut|Interviews

Beauty queenpin: ‘Deli Boys’ makeup head Nesrin Ismail on cosmetics as masks and mirrors

Design Juice

Rachel Paese|Interviews

A quieter place: Sound designer Eddie Gandelman on composing a future that allows us to hear ourselves think

Design of Business | Business of Design

Ellen McGirt|Audio

Making Space: Jon M. Chu on Designing Your Own Path

Design Juice

Delaney Rebernik|Interviews

Runway modeler: Airport architect Sameedha Mahajan on sending ever-more people skyward

Recent Posts

Minefields and maternity leave: why I fight a system that shuts out women and caregivers Candace Parker & Michael C. Bush on Purpose, Leadership and Meeting the MomentCourtney L. McCluney, PhD|Essays

Rest as reparations: reimagining how we invest in Black women entrepreneurs Food branding without borders: chai, culture, and the politics of packagingRelated Posts

Arts + Culture

Alexis Haut|Interviews

Beauty queenpin: ‘Deli Boys’ makeup head Nesrin Ismail on cosmetics as masks and mirrors

Design Juice

Rachel Paese|Interviews

A quieter place: Sound designer Eddie Gandelman on composing a future that allows us to hear ourselves think

Design of Business | Business of Design

Ellen McGirt|Audio

Making Space: Jon M. Chu on Designing Your Own Path

Design Juice

Delaney Rebernik|Interviews

Jade Dressler is a curator to consumer brands and private clients on art and design, providing content, media, exhibits, interiors, clothing collections and urban interventions.

Jade Dressler is a curator to consumer brands and private clients on art and design, providing content, media, exhibits, interiors, clothing collections and urban interventions.