April 10, 2018

Double or Nothing: Can designers erase the gender pay gap?

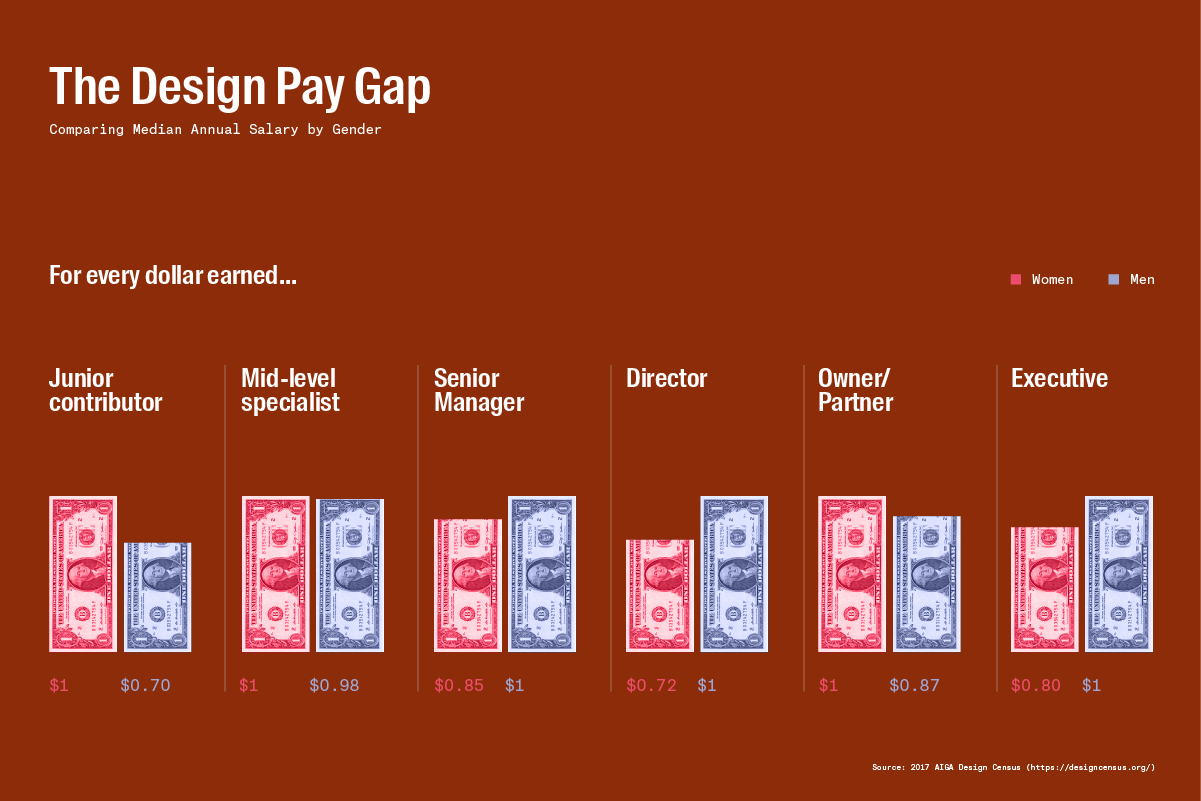

Visualization courtesy Nikki Chung and Dungjai Pungauthaikan, Principals at Once-Future Office. Source: 2017 AIGA Design Census.

On Equal Pay Day, three of the designers leading the new AIGA Women Lead campaign, Double or Nothing, talk about what they’re doing to make the gender pay gap a thing of the past.

Equal Pay Day is marked on our calendars not in recognition of a particular event that happened on this date, but rather, as a marker of an ongoing reality. More than anything, Equal Pay Day is a symbol; a date that represents the fact that women on average have to work a year and four months to earn the salary a man receives in one.

There have been conversations about the long-standing biases and structural impediments that created a disparity in leadership positions and a gender pay gap for years now. (Although, as the Pew Research Center recently showed, conversations are often along partisan lines). Art historian Linda Nochlin wrote the famous essay “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?” as a challenge to museums in 1971. The Guerilla Girls are asking a similar question today. Dior’s most recent Spring 2018 collection channeled Nochlin (to some controversy) too, 47 years after the original essay was published.

The hard numbers show a similar disparity, and frustratingly, one that isn’t new. Women hold just a small portion of leadership positions in the design industry. The gender wage gap has narrowed less than a percentage point in the last year, according to data released by the U.S. Census Bureau. Based on the median earnings of all full-time, year-round workers in 2016, women make 80.5 cents for every dollar men make, a change from 79.6 cents the previous year. AIGA has released data from its 2017 Design Census, and as you’ll see from the graphic above, the pay gap within the design community is not so different.

Double or Nothing identity created by Emily Oberman’s team at Pentagram.

So, with this aggregation of data, the question becomes not if, but how? How can it be remedied? As it turns out, designers have responded: Ladies Get Paid; Ladies, Wine & Design; Where are the Boss Ladies?; The Wing. In politics, there’s She Should Run. The co-chairs of AIGA’s Women Lead Initiative, Lynda Decker, Decker Design; and Heather Stern, Lippincott, have launched Double or Nothing with the distinction of a clear goal: to double the number of women in leadership positions within the next two years.

A symbol, like Equal Pay Day, is a tool often used by designers to convey a message. As a profession, designers are expert in taking an abstract concept and compressing it into a mark or campaign. Equal Pay Day was first initiated in 1996 by the National Committee on Pay Equity. We’ve had the symbol. The question now is, how will we clarify the call to action for our industry?

A symbol, like Equal Pay Day, is a tool often used by designers to convey a message. The question now is, how will we clarify the call to action for our industry?

I spoke to three of the women spearheading Double or Nothing—Heather Stern, Chief Marketing & Talent Officer at Lippincott; Emily Oberman, Partner at Pentagram; and Laura Kunkel, Creative Director at Blue State Digital; about their career paths and how they challenged notions of parity along the way. These women might come from different worlds and workplaces, but the road to gender equity is one we all have to navigate together.

HEATHER STERN, CHIEF MARKETING AND TALENT OFFICER, LIPPINCOTT | CORPORATION

How have you grown since the first Equal Pay Day in 1996, and has your view of the workforce changed?

I think at the beginning of your career you’re very green and you accept things for what they are. You’re not interested in rocking the boat. As you get exposed to different people and experiences, you realize there are important conversations you need to be having to question the status quo and to have a more active role in giving yourself agency.

Was your mother, or another woman in your life from the generation before you, in the workforce? How has her experience influenced you?

I worked with journalist Gail Sheehy. She was a feminist at heart. Watching her navigate her own career; her don’t-take-no-for-an-answer attitude; the ambition she had was inspiring and helped from a very early age provide a model for me as someone who was the opposite of a wallflower and had been very successful at doing so. She showed me in a real tangible way how to embrace your confidence and believe in yourself.

Talk about this campaign. Why did you take this challenge on and why now?

I had the pleasure of partnering with Su Mathews Hale, Deb Adler, and Lynda Decker when AIGA Women Lead started. As a member of the business community and a woman and mother, it’s close to my heart. It just felt like there was such a groundswell of what’s going on with Time’s Up and #METOO and looking at everything that’s coming out. It just felt like now’s the time to do something bold and ambitious and put a stake in the ground that we are part of this broader movement and that we have something to say in the design community. What does that uniquely look like in the design industry? We’re really hell-bent on creating change.

Now’s the time to do something bold and ambitious; to put a stake in the ground that we are part of this broader movement and have something to say in the design community.

By taking the helm of the Double or Nothing campaign, you’re attempting to redesign a system. What’s your ambition?

From the beginning, we put a stake in the ground and asked—what are we actually trying to do here? Doubling the number of women in leadership positions. How are we actually going to do this? It’s not a pipeline problem—it’s pay gap. So, it involves talking to various experts to determine how they tackle this. After talking to Blue State Digital, we thought like a political campaign: How do we get people saying they want to do something? That’s phase one.

Phase two is to give people the right tools or resources to think about their careers holistically.

Phase three is impact. A double or nothing pledge: developing a set of tangible actions that companies need to take to move the needle in the right direction. We want people to say publicly, yes we believe in this and we’re going to adopt this set of best practices to make this a reality.

A lot of this had been not quite knowing and having the courage to move forward while admitting we don’t know all the answers. The typical marketing campaign—you know how it’s going to be seeded and there’s a clear tangible output. We’ve been very open.

The broader hope is that through this people are given tangible tools, advice, and behavior that they can adopt to actually make a change and that we have as many companies as possible agreeing to our challenge to commit to making that change. On a small scale, it’s wanting to educate, inspire, and connect people to this. On a broader level, we want to see a change in percentage in the amount of women in leadership roles.

I’m a designer. What can I do tomorrow to help close the gender pay gap?

Obviously through studies like the Design Census, there’s a sense of where people should be at different stages of their career. Be aware and know what you’re worth, and ask for it without any apology.

Be aware and know what you’re worth, and ask for it without any apology.

EMILY OBERMAN, PARTNER, PENTAGRAM | INDEPENDENT AGENCY

Equal Pay Day was started in 1996 by the National Committee on Pay Equity. Where were you working in 1996? And what kind of job was it?

I was at Number 17, my own company with my partner Bonnie Siegler. It was a small, boutique design studio. We did all kinds of work—for entertainment, magazines, books. We were a women-owned company, often mostly staffed by women.

How have you grown since then, and has your view of the workforce changed?

I’m able to do things more quickly. My general zeitgeist or raison d’être for what I do hasn’t changed that much, but the way I work is more efficient. I’m a better art director. I understand typography and spatial relationships a million times better. I can see things more clearly and concisely. I don’t know, maybe that comes with a larger team.

I like to do good, smart work for good, smart people. That means for both the client and the audience. I like design to have a clear idea and an amount of wit; a little bit of surprise; an “aha” element, where you’re rewarded a little bit more if you look at it closely.

Was your mother, or another woman in your life from the generation before you, in the workforce? How has her experience influenced you?

I’ll give you four.

My mother. My mother is a painter, sculptor, illustrator. She was always creative in everything she did. She always put a wink and something special in her work. She always approached things with humor, sarcasm, and insight. Her paintings were witty and also really good. She worked hard on them but they were also a little bit funny. For example, my mother had an exhibition and the way she named her paintings was by putting fortunes she saved from fortune cookies next to the paintings as their titles.

I worked at M & Co., and Maira Kalman was a huge influence on me in her quirky way of looking at illustrating things. She was driven. She always embraced joy and silliness and weirdness. She did a beautiful job of embracing sorrow—in order to have happiness you have to have sorrow. She made me keenly aware of that.

Bonnie Siegler, my partner at Number 17. The two of us always wanted to do work that made us think a little bit more. We always tried to solve problems in a way that was different from what the client asked.

And, the answer that every woman designer gives—Paula Scher. She’s just the best. She’s never not smart. She’s always thinking about something in a new way. She doesn’t take crap from anyone—including her clients. She’s a great speaker and educator, and she doesn’t suffer fools.

Why was it important for you to get involved in the Double or Nothing campaign?

It’s funny because I would say that, throughout my career, I never felt particularly marginalized because I was a woman or because Number 17 was a woman-owned company. But now that I say that, I don’t know that that’s true. I might have viewed things with rose-colored glasses. I learned to accept that as a part of life. Everything changed when Hillary did not become President. The fact that she was a woman and the way that we talked about her—that whole feeling that we had collectively while working with The Wing, and at the time we were going to have the first woman president—was a warm, nurturing feeling.

When it flipped, it became a different feeling. We had to have a place of our own in order to start making a change. The #MeToo movement and all that it represents—all of these voices coming together and talking about this–was a natural evolution of the work we were doing at Pentagram.

There’s this idea that just being a woman is political. Taking something that I do and being able to use it for good seemed like a no-brainer to me.

There’s this idea that just being a woman is political. We talked about this with Michael Beirut’s campaign, It’s a Real Mother. We started talking about the idea that not only do women make less, but when you have a child, women’s pay goes down and men’s pay goes up.

So when AIGA came to us and talked about doubling the amount of women in leadership and fight for equal pay it became something I absolutely wanted to get involved with. And we started working with other activist campaigns. All of this starting to happen at the same time and I think it’s because of the political climate of the country. We’re fed up. Enough’s enough. I’m at Pentagram and I’m a mother. Taking something that I do and being able to use it for good seemed like a no-brainer to me.

LAURA KUNKEL, CREATIVE DIRECTOR, BLUE STATE DIGITAL | “PURPOSE-DRIVEN” AGENCY

Can you reflect on what Equal Pay Day means to you?

In my family, as the oldest child, I’ve had more conversations with my parents about their expectations of me as an investment—I know that sounds weird. But I think that it’s been a struggle to get my dad to understand what we’re still facing. Having gone to college and as a young creative director, it was hard to get him to appreciate that it is a lot of work. What I appreciate about this campaign is this missed point of receiving promotions that seem more easily achievable by men. We understand what bias looks like and it’s easy to recognize these biased behaviors in other people. We were all in art school at the same time but some are art directors and others aren’t.

Can you expand on what you called a “missed point” in understanding the gender pay gap?

We don’t have a pipeline problem, which is a really popular thing to point out in the diversity and inclusion conversation. There are tons of women graduating from design school but we’re not promoting them. The moment we’re in is coming off decades of conversation around bias. We’re familiar with it but we don’t know how to overcome it. So we’re focusing on giving those seeking leadership positions tools to overcome that.

That’s important because these conversations are really hard to have: no one wants to be the one that’s pointing out things that are sexist or unfair. At Blue State that’s particularly easy. A lot of colleagues want to be a part of this change. The work that we’re realizing now is work that you have to do yourself. It’s not work that a system or organization will do for you; making sure your organization is looking at the numbers and the hires that they’re making. Ethics training should really be about how you train other people. How can unbiasing be like hygiene work that’s entered into the culture?

Equal Pay Day was started in 1996 by the National Committee on Pay Equity. Where were you working in 1996? And what kind of job was it?

In 1996, I was probably in middle school, being emotional.

Was your mother, or another woman in your life from the generation before you, in the workforce? How has her experience influenced you?

My mother worked in advertising before she had me. I was always acutely aware that I was the reason that she didn’t go back to work. I had a keen sense of her career and the difficult path she had in that career was something she had a lot of pride in. I was always sad that she couldn’t be a working mother in the ‘80s and not a lot has changed around that.

She was a Peggy Olson character—she came in as a typist. Part of what happened in that time period was that they’d have in-house casting. One of her favorite things as a secretary to this creative director was to run casting; but even though she was involved in coordinating shoots, she was never involved in the shoots on set. Basically they’d invite a lot of hot models and you can imagine what that was like.

She started pitching ideas to a casting director and this fantastic woman, Vangie Hayes, really took her under her wing. She spoke of her with a lot of reverence, which just shows you how important having mentors can be. But you can imagine having a baby was untenable, because there were so many men in advertising in the ‘80s. It was still super sexist. They said, “We knew you weren’t going to come back.” And otherwise your whole salary would go to child care. It seems like there’s a real gap there—coming back to work after having a family. It still seems weird that you have to make a choice.

What’s the biggest challenge for Double or Nothing?

I think a big challenge of this issue is that bias is so difficult to measure. We don’t know what we’re measuring and what we’re measuring against. One of the biggest challenges is getting people to report on the numbers. The more and more companies that we can get on board with this campaign to look at themselves critically about not being where they want to be—just that transparency has value in the culture at this juncture. We don’t know what we don’t know.

I think a big challenge of this issue is that bias is so difficult to measure. We don’t know what we’re measuring and what we’re measuring against.

One of the potential impediments to our progress is people being too fearful of the shame around how complicit they are and determining who accepts responsibility for that. Part of the answer is I think that everyone has to. We’re designing the campaign with the design community to show that it’s not just at the top. Yes, it’s people that are designing hiring and promotion processes, but it really requires the most diligence from line managers who have the power to make sure that there’s parity in the opportunities they’re giving women and that there’s a fair pay structure across their team. Since I’ve started working on this I’ve noticed a lot of men in my company ask me how they can be a better advocates. You’re forced to ask yourself, what would I have benefited from had I been conscious of the experience I have now?

By taking the helm of the Double or Nothing campaign, you’re attempting to redesign a system.What skills does it require?

It requires an openness to messiness, progress, and process. We’re coming together as a group of women that have had very differently defined designed processes. That’s a difference in my background—I’m more comfortable with the messy movement-building and getting the feedback. In traditional design processes, we’re used to placing a lot of limitations around the ways that you’ll change a design, product, or program just to keep a timeline moving. Especially because we don’t know how long this will take, it’s important to lean into that freedom to make design choices based on feedback. Also, what is it like to engage in a really fractured design community that has different preferences? A lot of the work will be how are we offering content, tools, strategy, and support that are actually useful and doesn’t become a chore so people stop doing work. That’s really hard. As designers, we want something to be beautiful and inspiring. We’re all communicators.

Agility is an imperative. If we just become a group of people pushing our content—that’d be disappointing; another group of women saying things need to change. What do you do next? In the abstract we understand that culturally, women aren’t provided with negotiating tools organically through mentorship in the way men are. There’s all sorts of biases at play that we recognize after the fact but we don’t really know what to do about it. Mentorship is important. But if there aren’t a lot of women in leadership—who’s mentoring you? How do they know what you’re facing? It’s just such a complex web of shit.

It’s just such a complex web of shit.

Parity in pay particularly makes me hopeful. Because it’s about numbers. It’s doesn’t require the same lift as addressing implicit biases because you can look at the numbers and say you’re going to make those changes. Looking critically at pay equity seems like a no brainer for an agency. You don’t want to be a part of that in this day and age.

I’m a designer. What can I do tomorrow to help close the gender pay gap?

You might ask a male colleague that works somewhere else what they make. I’d start having dialogues with people. Maybe you ask HR, how are we doing around pay equity? Turning the heat on is something that we can all do. Ask each other what we’re making and don’t be shy about asking those questions. It’s about holding leadership’s feet to the fire and saying that we’re paying attention to how women are paid and treated.

Observed

View all

Observed

By Lilly Smith

Related Posts

Design Juice

L’Oreal Thompson Payton|Interviews

Cheryl Durst on design, diversity, and defining her own path

Arts + Culture

Jessica Helfand|Interviews

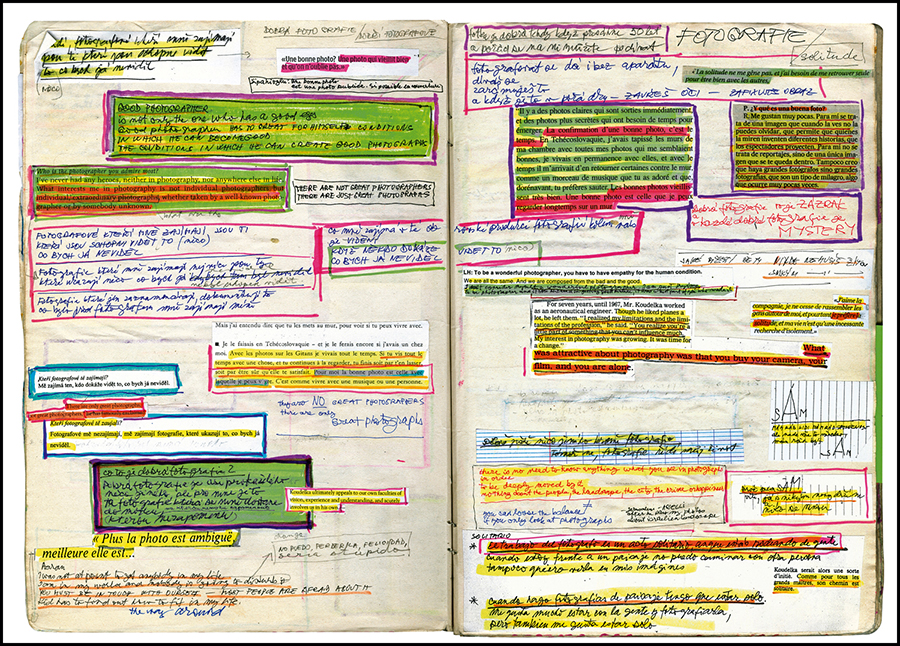

Josef Koudelka, Next: A Visual Biography: Ten Questions for Melissa Harris

The Editors|Interviews

GOOOOOOAL

Books

Jessica Helfand|Interviews

Henry Leutwyler: International Red Cross and Red Crescent Museum

Related Posts

Design Juice

L’Oreal Thompson Payton|Interviews

Cheryl Durst on design, diversity, and defining her own path

Arts + Culture

Jessica Helfand|Interviews

Josef Koudelka, Next: A Visual Biography: Ten Questions for Melissa Harris

The Editors|Interviews

GOOOOOOAL

Books

Jessica Helfand|Interviews