April 28, 2011

Educating for a Future Within Our Sight

“Pluralism is always practical,” famously declared Nabokov. By that measure, Rita J. King, journalist, nuclear expert, virtual worlds scholar, VP of business development at Science House and IBM Innovator-in-Residence — is a bastion of postmodern pragmatism. Her latest project, a collaboration with Joshua Fouts, is the product of more than two years of research, exploring the future of education and work through a concept King calls the Imagination Age — a fleeting period between the industrial era crumbling behind us and the technological hyper-reality glimmering ahead of us, in which we have the rare chance to reimagine our culture, our economy, our world and our place in it.

IMAGINATION: Creating the Future of Education and Work explores how we can harness the unique opportunities of this new age and reshape the education system. The project offers a portal of resources for educators spanning a wide range of media, disciplines and potential applications. Maria Popova sat down with King to talk about the scope of the work, the role of imagination in academia and the cross-pollination of disciplines as a key enabler of creativity.

Maria Popova: At the core of this project is a sociocultural era you call The Imagination Age. Could you elaborate on it and what observations first led to its conception?

Rita J. King: The Imagination Age is a fleeting period between two longer eras: the fading industrial era rusting behind us and the hybrid reality that hasn’t yet fully taken shape, but will. It was catalyzed by a child’s comment that she was afraid that her imagination would die when she became an adult. The project begins with a quote from Ursula Le Guin, “The creative adult is the child who has survived.”

Machines aren’t yet smarter than humans, so we have this time to imagine the implications of what will happen when they are, and how we can redesign the cultural and economic systems that govern our shared lives on this tiny blue planet.

Imagination leads to collaboration, rapid prototyping, a deeper understanding of failure as part of the process and the ability to think in the long-term despite the accelerated pace of transformation. Imagination is the most effective path to balance between each individual and the global culture and economy.

Popova: The cross-pollination of ideas across disciplinary boundaries is essential to creativity and innovation. Based on your research, how do current educational models and curricula hinder this and what are the most viable potential changes you’ve identified to foster rather than inhibit such cross-disciplinary education?

King: Current educational models prepare students for a fading industrial era, but making substantive changes is difficult. It’s hard to know where to begin and how. This project focuses on shifts educators can instantly make at no cost.

For example, chapter 17, “Focus on STEM,” includes a video of the founding director of the National Institute of Aerospace, Robert Lindberg, explaining the difference between the Scientific method and the Engineering Design Process. A scientist and an engineer, Lindberg points out that students aren’t educated about the critical difference between the two.

The skills required for success in the Imagination Age (particularly in science, technology, engineering, art and mathematics) require a collaborative approach. Students in the American public education system are still bound by solitary test-taking and individualistic achievement and failure models. This runs counter to the reality of the emerging global labor market.

Popova: How has your research on virtual worlds enriched and informed this exploration of the future of education and work?

King: Geographically dispersed learners, or even those who are in the same room in the physical world, can create environments that inspire a sense of discovery and a team-based approach.

Many educators fear the loss of control in such environments because they haven’t been trained to teach in them, but a billion human beings currently participate in some form of virtual environment, and half of them are under the age of 16.

Virtual environments are ideal for gaining proficiency, if not mastery, of core subject areas. How many people remember the difference between an equilateral, isosceles or scalene triangle? In a virtual environment, students can manipulate a triangle or any other object to change the shape. They can actually become a white blood cell, moving through a digital bloodstream and learning about the processes that occur invisibly on a much smaller scale. In this way, learning becomes far more vibrant.

Popova: In a meta kind of way, the project is also a case study in the future of research itself and the practical applications of its findings. Why did you choose not to publish it as a book or white paper, and what role do you think design will play in the future of how we present, process and act on such information?

King: Publishing in this format is a demonstration of how modern tools can be utilized to reflect the spirit of the subject matter: imagination. Traditional book publishing remains a lengthy process, with a long time between manuscript completion and publication. Why not publish a book in pieces, with each short and interactive piece embedded with relevant multimedia?

The information in the IMAGINATION project is current, so we wanted to get it out there and let it have a life of its own so we could get back into the field. Since our subject matter is imagination and the culture shift required to put it into practice, we wanted the most useful and interactive format possible.

We can design better systems and create better lives for ourselves and others. Aesthetic beauty and functionality should exist in equal parts in every design. This principle is one of the core tenets of the Imagination Age.

Popova: What has been the most surprising finding throughout the course of this project?

King: The most surprising findings were beyond the scope of the focus of IMAGINATION and were therefore not explored on the site. For example, the trend toward pharmaceutical intervention for boredom at school is a major issue. We were also surprised to learn that some districts, such as Pennsylvania’s Lower Merion, have used laptop webcams to monitor students at home. These issues require further examination in the appropriate forum.

Many educators are enthusiastic about exploring technology but others perceive it as dehumanizing. A few years ago I saw an article of a graduating class throwing caps into the air while one girl texted. The caption indicated how sad this was. But maybe she was connecting with someone important to her who couldn’t be there due to illness, cost or timing. Technology enables deeper connections. The potential of the young to maximize this level of creative connectivity should be fostered.

Observed

View all

Observed

By Maria Popova

Related Posts

Arts + Culture

Jessica Helfand|Interviews

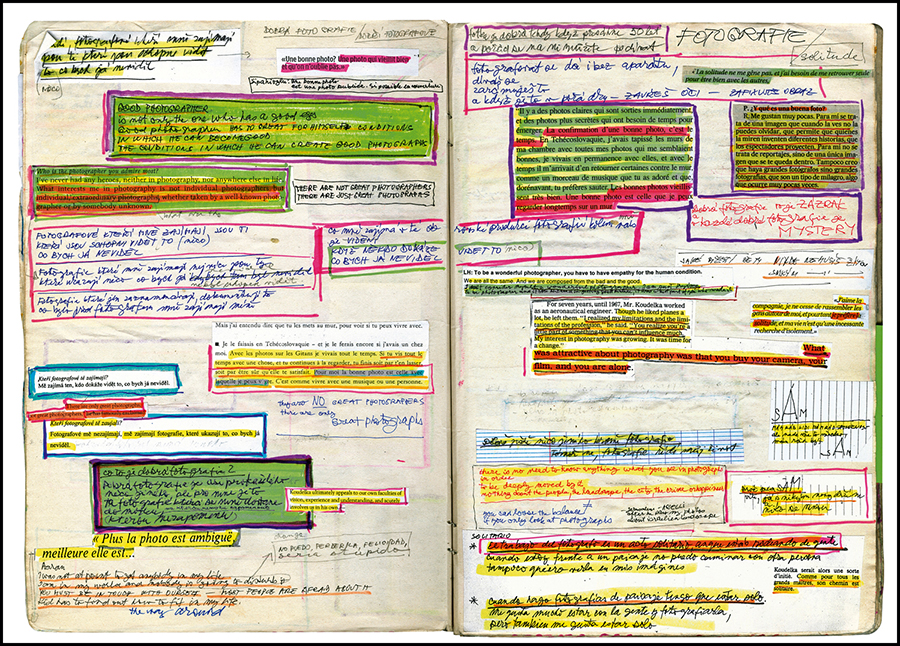

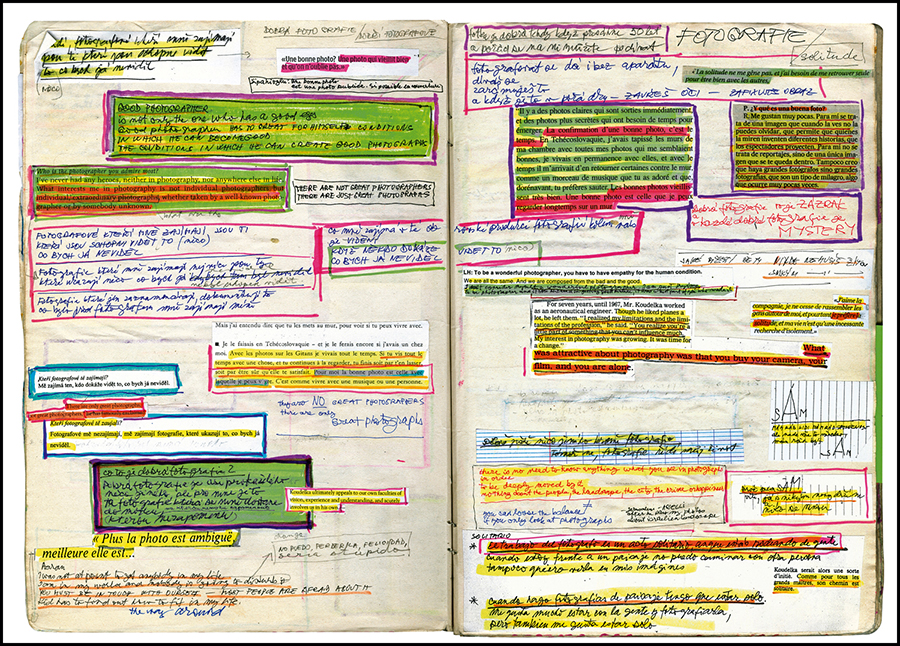

Josef Koudelka, Next: A Visual Biography: Ten Questions for Melissa Harris

The Editors|Interviews

GOOOOOOAL

Books

Jessica Helfand|Interviews

Henry Leutwyler: International Red Cross and Red Crescent Museum

Education

The Editors|Interviews

Ritesh Gupta + Useful School

Recent Posts

Make a Plan to Vote ft. Genny Castillo, Danielle Atkinson of Mothering Justice Black balled and white walled: Interiority in Coralie Fargeat’s “The Substance”L’Oreal Thompson Payton|Essays

‘Misogynoir is a distraction’: Moya Bailey on why Kamala Harris (or any U.S. president) is not going to save us New kids on the bloc?Related Posts

Arts + Culture

Jessica Helfand|Interviews

Josef Koudelka, Next: A Visual Biography: Ten Questions for Melissa Harris

The Editors|Interviews

GOOOOOOAL

Books

Jessica Helfand|Interviews

Henry Leutwyler: International Red Cross and Red Crescent Museum

Education

The Editors|Interviews

Maria Popova is the editor of

Maria Popova is the editor of