Exposure • Media • Photography

August 18, 2015

Exposure: Rossellini and Lynch by Helmut Newton

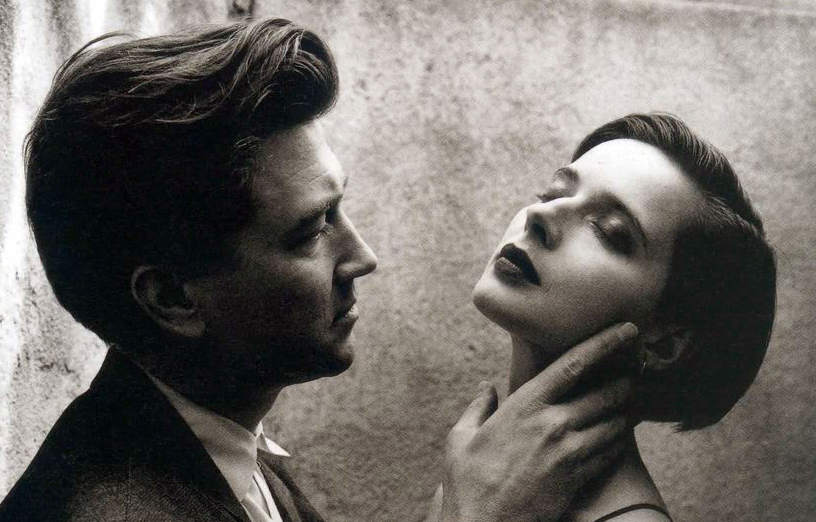

David Lynch and Isabella Rossellini by Helmut Newton, Los Angeles, 1988

In the late 1980s, David Lynch and Isabella Rossellini were an item. Lynch had chosen her to star in Blue Velvet, a disorientating voyage into the darkness beyond the small-town picket fence that was instantly acclaimed by critics as a landmark film. Rossellini’s performance as the abuse victim Dorothy Vallens is unforgettable. On their first meeting, Lynch famously told the Lancôme model and actress that she looked like the daughter of Ingrid Bergman (which she is). They were together for four years and she also appeared in Lynch’s Wild at Heart. She has said he was the love of her life.

It’s hard to imagine a more fitting photographer for the couple than Helmut Newton (1920–2004), who often drew criticism—as did Lynch with Blue Velvet and other films—for the sexual politics of his images. Are Newton’s fashion and society pictures exploitative or empowering, sleazily voyeuristic or legitimately erotic, or all of these things at once? His luscious, shiny, film-noirish technique makes the question difficult to answer. The sleek black-and-white pictures feel authentic: true to the sensibility and desires of the man, and true to his unshy, déshabillé participants, who inhabit these scenes with monumental composure. Like Lynch, Newton reveals impulses in the viewer that may be uncomfortable to face.

The walls alone are enough to convey a sense of two figures trapped in the pressure cooker of their own obsessions. The immaculate lighting of their faces turns them into perfectly hewn sculptures. Rossellini may be taking the photographer’s direction and acting, or she may be lost for a moment in a transport of bliss. “Photography always has been my medium,” she told Interview magazine, “and I’ve always felt that what ultimately makes a great photo is the emotion that comes across.” But what is Lynch feeling? Is this the face of an enraptured admirer, or someone coolly sizing up a trophy, like a fabulous Ming vase? The hand, engaged more in a hold than a caress, is a little disturbing. Are we meant to think of throttling? The image is erotic—the tilted head, the full lips, the curve of the eyelids—yet it’s also cold, as Newton’s pictures are often both hot and cold, and the rough wall could easily scrape bare flesh.

Another star is also emerging here. As he grew older and turned gray, Lynch’s elaborately barbered hair became ever more photogenic. One admirer even compared its moods and waves to brushstrokes in famous paintings. The double portrait is an early outing for the retro-styled, luxuriant, Lynchian quiff, and in this primal lovers’ tryst, Newton makes full use of its unbridled masculine eloquence.

Observed

View all

Observed

By Rick Poynor

Related Posts

Exposure

Rick Poynor|Exposure

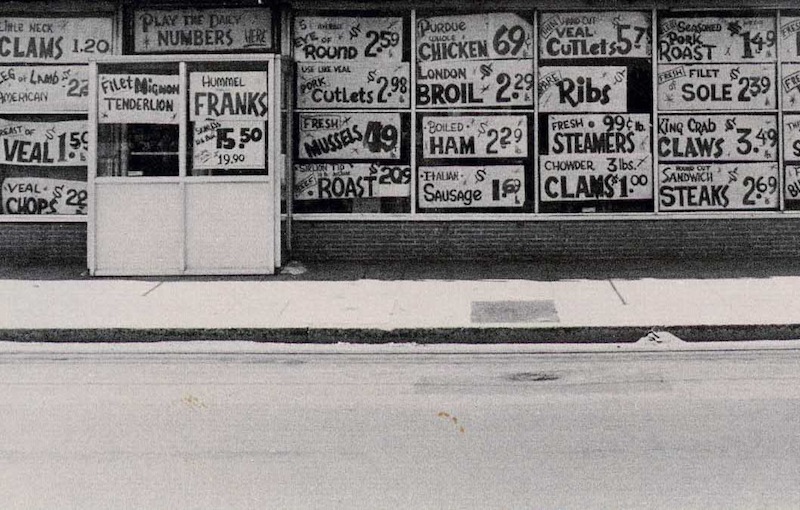

Exposure: Andy’s Food Mart by Tibor Kalman and M&Co

Exposure

Rick Poynor|Exposure

Exposure: License Photo Studio by Walker Evans

Arts + Culture

Rick Poynor|Exposure

Exposure: Drape (Cavalcade III) by Eva Stenram

Arts + Culture

Rick Poynor|Exposure

Exposure: Mrs. E.N. Todter by Dion & Puett Studio

Recent Posts

Why scaling back on equity is more than risky — it’s economically irresponsible Beauty queenpin: ‘Deli Boys’ makeup head Nesrin Ismail on cosmetics as masks and mirrors Compassionate Design, Career Advice and Leaving 18F with Designer Ethan Marcotte Mine the $3.1T gap: Workplace gender equity is a growth imperative in an era of uncertaintyRelated Posts

Exposure

Rick Poynor|Exposure

Exposure: Andy’s Food Mart by Tibor Kalman and M&Co

Exposure

Rick Poynor|Exposure

Exposure: License Photo Studio by Walker Evans

Arts + Culture

Rick Poynor|Exposure

Exposure: Drape (Cavalcade III) by Eva Stenram

Arts + Culture

Rick Poynor|Exposure

Rick Poynor is a writer, critic, lecturer and curator, specialising in design, media, photography and visual culture. He founded Eye, co-founded Design Observer, and contributes columns to Eye and Print. His latest book is Uncanny: Surrealism and Graphic Design.

Rick Poynor is a writer, critic, lecturer and curator, specialising in design, media, photography and visual culture. He founded Eye, co-founded Design Observer, and contributes columns to Eye and Print. His latest book is Uncanny: Surrealism and Graphic Design.