June 8, 2005

Decoding Coldplay’s X&Y

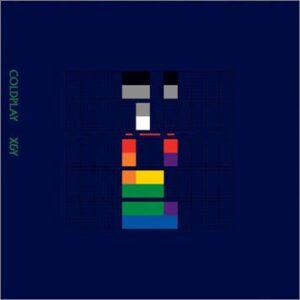

X&Y by Coldplay, designed by Tappin Gofton, EMI, 2005.

At a time when invisible data streams of binary information fed straight to our desktops are doing away with the need for album covers, it’s odd to find a record sleeve as the subject of media comment and speculation. Odder still that the album cover in question — Coldplay’s X&Y — should contain binary data as its central motif. Prophetic or what?

The Coldplay sleeve has been designed by hot new graphics duo Tappin Gofton. They have good pedigrees: Mark Tappin was at Blue Source, Simon Gofton at Tom Hingston Studio, both important studios in the UK music design scene. Until the appearance of their Coldplay sleeve, Tappin Gofton were best known for their 1960s-style “agit-prop” cover for The Chemical Brothers album Push the Button. Their work for Coldplay’s third album establishes them as a new force in contemporary music design.

With the record industry’s habitual love of hyperbole, Coldplay are being touted as the “world’s biggest band”. They certainly sell records. Earlier this year, their British record label EMI was forced to issue a profits warning to its shareholders when the band delayed the release of X&Y. Lead singer Chris Martin (referred to in the UK tabloid press as Mr. Gwyneth Paltrow) responded by announcing: “I don’t really care about EMI. I’m not really concerned about that. I think shareholders are the greatest evil of this modern world.” Martin is an unlikely candidate to announce the end of capitalism. Middle class, privately educated and married to Hollywood royalty, he and his band generate enough income to equal the earnings of a small corporation. Their last album, A Rush of Blood to the Head, sold 11 million copies and it’s easy to imagine EMI’s shareholders forgiving Martin’s lippiness if sales of X&Y exceed that figure.

The X&Y cover is agreeably eye-catching. You wouldn’t call it a classic, but it has an unexpected severity that lifts it above the anodyne and cosmeticised design currently favoured by multi-platinum selling artists. It has dark echoes of Peter Saville’s epochal Factory covers. To render the Coldplay name and album title, Tappin Gofton use Albertus, a typeface Saville deployed to memorable effect on the cover of New Order’s single “Ceremony” in 1981. And just as Saville did on his notorious floppy disk sleeve for New Order’s 12-inch single “Blue Monday” and his album cover for the same band’s Power, Corruption and Lies, both from 1983, Tappin Gofton use an enigmatic colour code and invite the viewer to decipher its meaning. It’s this graphic puzzle — rather than the “design” — that is causing the sleeve to be subjected to the sort of scrutiny not normally given to contemporary album covers, or graphic design in general, for that matter.

Blue Monday by New Order, designed by Peter Saville, Factory, 1983.

As early as April, Guardian art critic Jonathan Jones noted: “The designers, Mark Tappin and Simon Gofton, have created a digital logo which echoes every modernist school of painting from suprematism to De Stijl. They themselves cite 1940s mathematical abstraction. To the NME and the websites apparently obsessed with this image, it is, however, a cross between the Da Vinci Code and Fermat’s last theorem: the great brain-teaser of our time. Is it phallic? Is it a coded celebrity portrait? Guys, guys — have you thought of asking: is it art?”

More recently, in the same newspaper’s weekly science supplement, Marcus du Sautoy, professor of mathematics at Oxford, wrote gleefully: “If you don’t want me to spoil the excitement of working out Coldplay’s new album cover, look away now. First, the colours are irrelevant. The cover translates the album title into a binary code where each block of colour represents a 1 and a gap 0.”

Du Sautoy proceeds to decode the symbol. He identifies it as an example of a system devised in 1870 by Emile Baudot for telegraphists, where each letter of the alphabet is represented by a series of five 0s or 1s. The letter X, for example, is represented by 10111, and Y by 10101. Referring to the Coldplay graphic, he states: “The first column of colours on the cover shows a black and grey block representing a 1, followed by a gap representing a zero, then three more blocks of colour giving three 1s. The first letter in Coldplay’s title is the letter X. The last column gives us 10101 or the letter Y.”

On its website, the NME, the last of Britain’s weekly pop music journals, takes a less highbrow view and likens the design to the 1990s computer game Tetris.

So: no oblique message announcing the overthrow of western governments and no coded references to the home addresses of EMI shareholders. Instead, a striking cover that has succeeded in exciting widespread comment — something that hasn’t happened much since David Bowie donned a dress for the original cover of The Man Who Sold the World and McCartney-is-dead theorists subjected the Beatles’ Abbey Road sleeve to forensic examination in the late 1960s.

Yet for graphic designers, two factors stand out amid this flurry of interest. The first is the continuing power of album cover art to provoke emotional responses from people normally unmoved by graphic design and visual culture. The melding of image and sound is a potent mix, perhaps unrivalled anywhere else in graphic design. The second is the perhaps unintentionally prophetic nature of Tappin Gofton’s sleeve. It can be read as an oblique commentary on the state of the music industry at a crucial moment in its short history. Digital downloading means that the record business is about to go supernova. It may be that Apple’s iTunes will become the world’s largest record company. Who knows? The one thing we can be sure of is that downloading music will increase and that, as a consequence, the album cover will disappear, or at least shape-shift into something more discarnate and less tangible.

The demise of the record cover has been under way since the arrival of the music video, followed by the shrunken canvas of the CD. Today, the album cover is just one of a dozen requirements for the successful marketing of music. The most important activity for the modern record company is getting artists onto magazine covers or into hit TV shows: the album cover is just one of many surfaces to be filled, no less or no more important than any other. Cover art will survive, encouraged by small independent labels and bands who crave a visual expression of their music. But as far as the major labels are concerned, if they could avoid spending money on record sleeves they would do it tomorrow.

The Coldplay cover, with its intriguing puzzle and uncommercial design, is an almost nostalgic statement of graphic simplicity. It can be viewed as a neat commentary on the death of the old record industry, but in the future it is more likely to be seen as a last hurrah for sleeve design and the notion of record covers as shared generational artifacts.

Adrian Shaughnessy is an art director, writer and consultant based in London. He contributes to Eye, Design Week, Creative Review, Grafik and the AIGA’s Voice website, and is editor of the Sampler series of books about music graphics. He is creative director of This is Real Art.

Observed

View all

Observed

By Adrian Shaughnessy

Related Posts

The Observatory

Delaney Rebernik|Analysis

A story of bad experiential design

The Observatory

Ellen McGirt|Essays

Lessons in wandering

Architecture

Sameedha Mahajan|Design and Climate Change

The airport as borderland: gateways for some, barriers for others

The Observatory

Alexis Haut|Analysis

“Pay us what you owe us”

Related Posts

The Observatory

Delaney Rebernik|Analysis

A story of bad experiential design

The Observatory

Ellen McGirt|Essays

Lessons in wandering

Architecture

Sameedha Mahajan|Design and Climate Change

The airport as borderland: gateways for some, barriers for others

The Observatory

Alexis Haut|Analysis