December 4, 2017

Memory of an Eclectic Modernist: Ivan Chermayeff

Despite his aristocrat-Russian-émigré-sounding name, Ivan Chermayeff was neither an aristocrat nor émigré (although he was born in London). But as co-founder in 1957 with Tom Geismar of the design firm Chermayeff & Geismar, he was nonetheless among New York’s design aristocracy—and the quintessence of Modern design itself. There are other Modernist-Bauhaus-influenced studios and firms in New York, yet Chermayeff & Geismar has long been known for its impressive imprint on the city through logos, installations, exhibitions, and posters.

In fact, this year marks the 60th anniversary of the firm Chermayeff Geismar & Haviv (Sagi Haviv became a partner in 2006) and on December 12, AIGA will mark this anniversary at Lincoln Center. Sadly, Ivan will not be there. He died this past Saturday, December 2. He was 85.

The first time I met Chermayeff, it was in an uber-modern office overlooking Madison Square Park in New York City with the largest reception room I’d ever seen (or what Tom Geismar wistfully refers to as “a colossal waste of space”). The tall slender man with the prep-school haircut and distinctive sculpted nose, wearing the requisite white shirt and tie came out to greet me. Ivan was as friendly as he was imposing, and fit the image that I had of a Modernist impresario.

Our first interview, for an oral history I was planning, lasted a few hours—during which I learned how the Yale-educated designer believed in a pragmatic idealism of designing for business and culture, and of his unmitigated adoration of design as a force for betterment on a grand scale.

I had perceived Chermayeff as the torchbearer of the orthodox Modern heritage, but I was surprised when he told me that Modernism is “not a religion, it’s a service.” Nor, he said, is Modernism “the ideological formulation it was for the post-World War II Swiss School (or Neue Grafik), known for prescribing graphic expression through strict formalist dictates.” Although Chermayeff & Geismar (starting as Brownjohn Chermayeff & Geismar) came of age in the mid- to late nineteen fifties, a time when International School standardization and grid-based composition was ascendant, they resisted slavish adherence to predigested form. Rather, Chermayeff & Geismar adhered to the much-discussed process known as the “play principle” as a means of staying open to accidental formal and intuitive relationships.

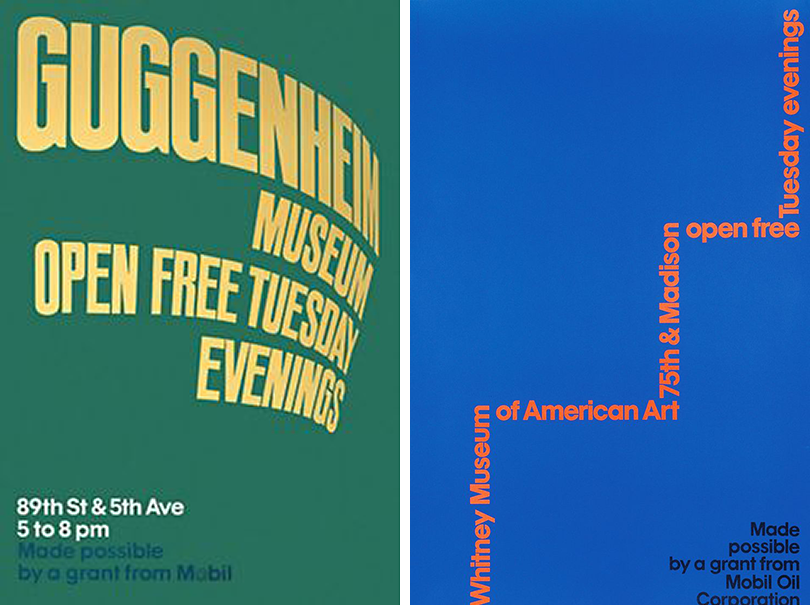

Chermayeff guided me through copies of his most playful work. There were dozens of conceptual paperback book covers and record albums that he and Tom designed from the early to late sixties replete with clever visual puns that were, in a sense, visual games. These subtle but effective methods of triggering an audience’s interest through design codes were key to Chermayeff & Geismar’s solutions. For example, in 1975, when Mobil Oil Company began sponsoring some of New York’s museums by keeping them open to the public on selected evenings, Chermayeff designed posters for bus shelters around the city, one each for the Whitney and the Guggenheim. Chermayeff told me that the common conceptual thread for each was the distinctive architecture of the Whitney, by Marcel Breuer, and Guggenheim, by Frank Lloyd Wright. “The type was done to wrap that distinctive hat of the Guggenheim so the hat and the type fit each other, while the Whitney’s message conformed to the upside down ziggurat.”

The reception space at the Madison Square Park office was filled with great art— especially an enviable collection of Saul Steinberg’s drawings. I don’t know how often Chermayeff used Steinberg’s work in his projects but I always associated the latter’s disciplined absurdity with the former’s precocious experimentation. Art was indeed a motivating force. “Our sources are art and artists, like Matisse, Picasso, Klee, De Kooning, Avery, Mondrian, Brancusi,” he told me. The work of these twentieth century visionaries was spiritually channeled into the firm’s graphic and exhibition design and was a respite from the rigors of professional design, Chermayeff said of the art of these outsiders and primitives, examples of which lined his shelves. So rather than follow formulae, Chermayeff was in business to engage, fascinate, charm, amuse, and even elicit awe in the person who encounters “the elegant line of type or pure formal gesture.”

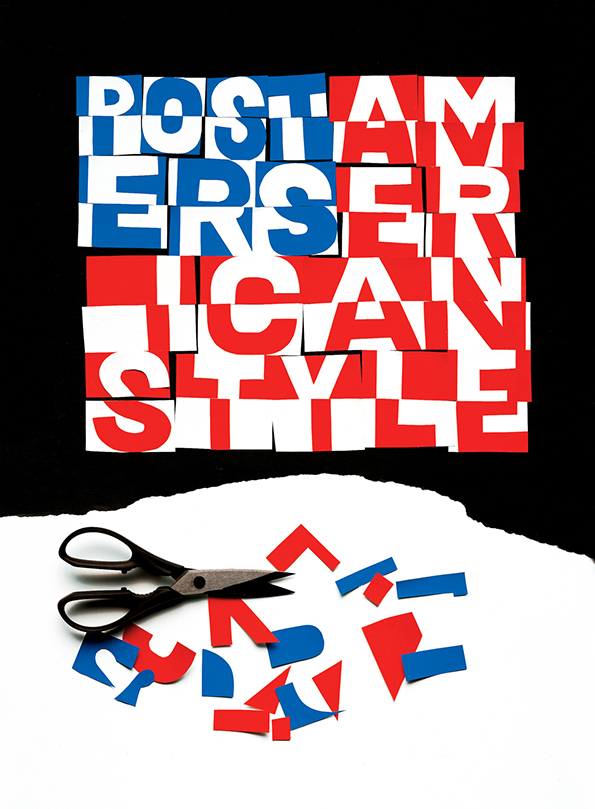

Chermayeff enjoyed working with collage because it enabled his curiosity and serendipity to flourish. Many of his posters, children’s books, and editorial illustrations were created as collages, some in the manner of Matisse. But there were more abstract ones as well. In fact, once, as a total surprise, I received a framed piece from Ivan with no explanation other than “Happy Tuesday.”

Surprise had long been one of Chermayeff’s tenets. First and foremost surprise was his gift to people, culture, and the city, too. Take the monumental architectural toy— the free-standing giant red number nine—on the sidewalk of the sloping skyscraper at 9 West 57th Street in New York City. Recalling its genesis, Chermayeff told me: “Why not make the slope the launching pad for the nine and land it on the sidewalk? Of course [the developer] understood this little architectural joke could be impractical since the cost of being on city-owned property outside the building’s boundary was considerably more expensive than the cost of putting the figure nine on the travertine façade, but to my surprise, the developer bought the idea.”

When Chermayeff & Geismar opened their design firm in New York, they carved a niche in what was a comparatively small field of designers as compared to what were then commonly called “commercial artists.” The number of individuals, firms, and studios doing work rooted in progressive design “ideals” were limited, and few Modernist design schools were educating the next-generation designers. The terrain was open for their firm to develop various long-term relationships with progressive, influential clients like Mobil, Time-Warner, Best Products, and Merck Pharmaceuticals, for whom they’ve developed identities with staying power. Ivan leaves a legacy. A firm that still bears his name is responsible for images we see every day. It is impossible to walk down a midtown Manhattan sidewalk without seeing an array of their logos, posters, shopping bags, and other commercial and cultural artifacts. Thank you, Ivan, for your service.

Observed

View all

Observed

By Steven Heller

Related Posts

Design Impact

Seher Anand|Essays

Food branding without borders: chai, culture, and the politics of packaging

Graphic Design

Sarah Gephart|Essays

A new alphabet for a shared lived experience

Arts + Culture

Nila Rezaei|Essays

“Dear mother, I made us a seat”: a Mother’s Day tribute to the women of Iran

The Observatory

Ellen McGirt|Books

Parable of the Redesigner

Recent Posts

Food branding without borders: chai, culture, and the politics of packaging Why scaling back on equity is more than risky — it’s economically irresponsible Beauty queenpin: ‘Deli Boys’ makeup head Nesrin Ismail on cosmetics as masks and mirrors Compassionate Design, Career Advice and Leaving 18F with Designer Ethan MarcotteRelated Posts

Design Impact

Seher Anand|Essays

Food branding without borders: chai, culture, and the politics of packaging

Graphic Design

Sarah Gephart|Essays

A new alphabet for a shared lived experience

Arts + Culture

Nila Rezaei|Essays

“Dear mother, I made us a seat”: a Mother’s Day tribute to the women of Iran

The Observatory

Ellen McGirt|Books

Steven Heller is the co-chair (with Lita Talarico) of the School of Visual Arts MFA Design / Designer as Author + Entrepreneur program and the SVA Masters Workshop in Rome. He writes the Visuals column for the New York Times Book Review,

Steven Heller is the co-chair (with Lita Talarico) of the School of Visual Arts MFA Design / Designer as Author + Entrepreneur program and the SVA Masters Workshop in Rome. He writes the Visuals column for the New York Times Book Review,