September 23, 2011

Quirky and “Design” as Entertainment

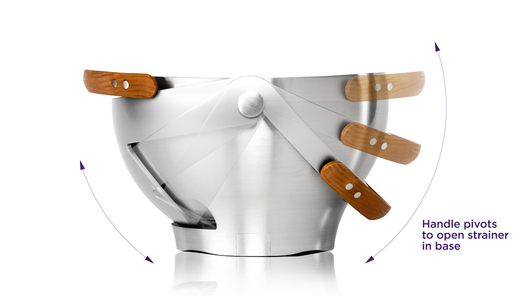

Ventu, “the new way to strain,” by Quirky.

“We’re all about reinventing the wheel,” Ben Kaufman, the young founder of Quirky, declares in an episode of the Sundance Channel television series about his company.

I’m sure that he did not intend to say that Quirky is “all about” completely pointless exercises in ginning up novel responses to problems that were solved, definitively, a long time ago. I’m sure of that because the show hammers away at the idea Quirky is, instead, a locus of “invention,” innovation, progress, original problem-solving, uniquely crowd-enabled creativity, and, perhaps inevitably, “design.”

I wrote a column about Quirky a couple of years ago, early in the company’s life. The premise is that anybody can submit a product idea, which is shaped by feedback from thousands of registered Quirky users (“the crowd”) and if all goes well the result gets funneled into the marketplace by the company. I haven’t paid attention to Quirky since then, but I was dimly aware that it was still going and seemed to be doing well (or at least getting lots of press). I had no idea there was a TV show about it until reading this lacerating review in the Washington Post, which said the show “eerily reflects the vapidity of the American economy and employment picture, where ideas trump labor and success is measured by top-level paydays instead of actual toil. Hipsters invent, while Chinese labor manufactures and shoppers mindlessly buy.”

Well, yes, isn’t that the system? But I digress. Anyway, the show sounded like something I ought to see. Having now watched a few episodes, I can say that as television entertainment, it’s quite poor. Every episode follows the path of two “inventors” and their product ideas. After some not-very-stressful hiccups, a product is created and goes up for sale and everyone is happy. The show does not acknowledge failures, so there’s no real suspense.

It’s hard to say how well Quirky reflects Quirky, but the Post review is correct in pointing out that on the TV version at least, the “inventor” turns out to be largely uninvolved in the process of converting her or his idea into reality. In a sense, this person serves as a sort of un-empowered client. After presenting an idea, he or she is essentially dismissed, and brought back periodically for updates on the design team’s progress. (The “crowd” doesn’t seem to contribute much either – there are occasional clips of random Quirky user piping up from the peanut gallery via Skype, but usually just echoing something that the in-house designers have already established.) Quirky’s design staff basically does everything, with Kaufman overseeing, rejecting, and approving whatever they come up with. Frequently the end product has little relationship to original concept, apart from being in the same broad category. This is the part, as Kaufman informs one inventor, where “we tear down your vision and turn it into a viable product.” If she’s unhappy, it’s a bummer, but it’s also kind of irrelevant: Quirky can’t be fired, and does not have to take orders. A design-firm dream come true, no?

Not so fast: trumping inventors and designers alike is Kaufman himself, with his eyes on the prize — sales, sales, sales. When Kaufman addresses the camera, he’s less Steve Jobs than Billy Mays, booming about “a paradigm-shifting can opener,” or “the new way to strain.” At one point he shouts: “We’re gonna make some products!” Um, cool?

If you’re paying attention to the show, you’ll note that a key element of inventions making it through the Quirky process isn’t actual design at all, it’s lining up an appropriate retail partner, a subject on which Kaufman can be amusingly blunt. The bowl/colander dubbed “the new way to strain” is executed in stainless steel, solely to lift it to “a much higher price point.” The fate of a leash is tied to distribution that targets “the top 2 percent of income earners.” Possibly this crass acknowledgement of what so much contemporary industrial design owes to the profit motive is off-putting to some. But I think it’s actually rather interesting to hear the usual design-establishment rhetoric about “ingenious solutions to everyday problems” baldly linked to excitable chatter about “a million-dollar idea” or “a big, giant check.” A typical climactic scene on the show involves Kaufman and an “inventor” standing around a warehouse filled with boxes and boxes of some alleged paradigm-shifter or other, talking about money.

Quirky is largely an hour-long infomercial for Quirky and its products. But maybe there’s some value in it just the same. Rhetoric aside, it does address rather directly the problem that I suspect dominates the careers of more than a few industrial designers. That is: How do we make this profitable?

Sometimes, perhaps, answering that one involves reinventing the wheel.

Observed

View all

Observed

By Rob Walker

Related Posts

Business

Courtney L. McCluney, PhD|Essays

Rest as reparations: reimagining how we invest in Black women entrepreneurs

Design Impact

Seher Anand|Essays

Food branding without borders: chai, culture, and the politics of packaging

Graphic Design

Sarah Gephart|Essays

A new alphabet for a shared lived experience

Arts + Culture

Nila Rezaei|Essays

“Dear mother, I made us a seat”: a Mother’s Day tribute to the women of Iran

Recent Posts

Courtney L. McCluney, PhD|Essays

Rest as reparations: reimagining how we invest in Black women entrepreneurs Food branding without borders: chai, culture, and the politics of packaging Why scaling back on equity is more than risky — it’s economically irresponsible Beauty queenpin: ‘Deli Boys’ makeup head Nesrin Ismail on cosmetics as masks and mirrorsRelated Posts

Business

Courtney L. McCluney, PhD|Essays

Rest as reparations: reimagining how we invest in Black women entrepreneurs

Design Impact

Seher Anand|Essays

Food branding without borders: chai, culture, and the politics of packaging

Graphic Design

Sarah Gephart|Essays

A new alphabet for a shared lived experience

Arts + Culture

Nila Rezaei|Essays

Rob Walker is a technology/culture columnist for

Rob Walker is a technology/culture columnist for