July 12, 2010

Teaching in a Time of Uncertainty

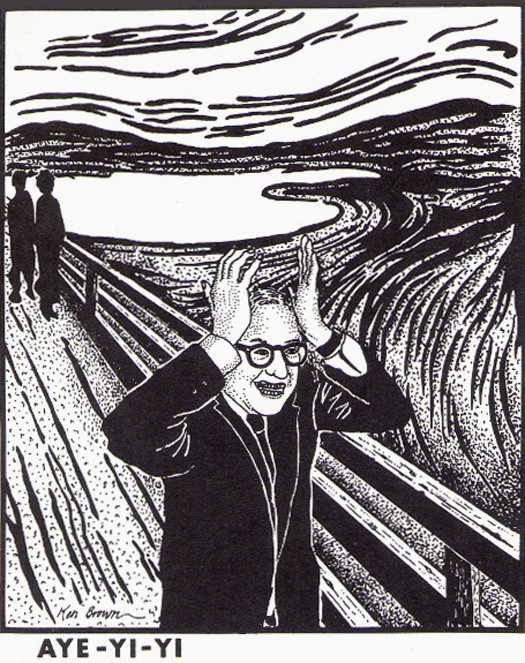

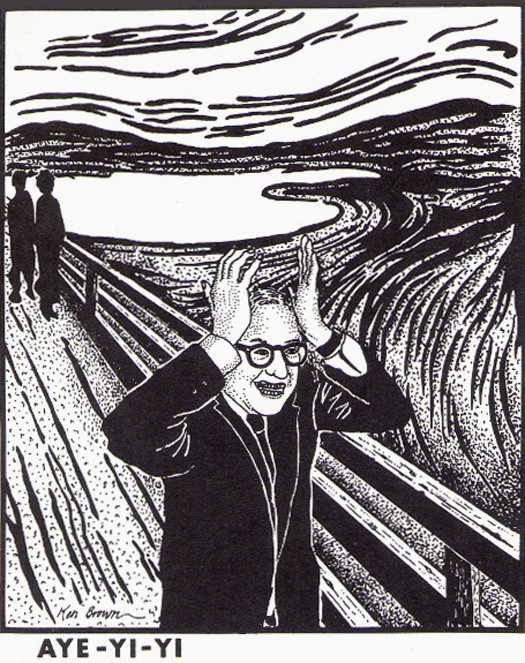

Postcard image by Ken Brown.

Since the beginning of professional industrial design — throughout the entire 20th century and into the first decade of the 21st — a designer has been a figure of confidence and authority. He (rarely, she) provided answers, solved problems, knew more than the public could possibly knew. A notion of an unsure designer, a questioning designer, or, heaven forbid, a doubtful designer would appear almost oxymoronic, and certainly unprofessional.

Perhaps the new decade will go down in history as marking the outset of Design Uncertainty. For the first time ever, designers are willing to question, openly and publicly, the nature of their profession and whether they are doing the right thing. This year, for the first time, an interrogation mark appeared in the title of the National Design Triennial at the Cooper-Hewitt. In the Netherlands, Eindhoven Design Academy’s 2010 exhibition in Milan expressed the same spirit of inquiry with an even more succinct title, a simple “?”

The reasons for self-searching and doubt are obvious, and they are not pretty. Two seemingly never-ending wars have contributed to political uncertainty and fueled fears of terrorism. The economic meltdown of 2008 continues to reverberate around the world. An unimpeded flood of oil gushes out in the Gulf of Mexico, in spite of the feats of the world’s best experts to stop it. Alice Rawsthorn, writing in The New York Times, recently captured the spirit of our time when she referred to design as “a quest for meaning in a dystopian era.” This existential mission, rather than a pursuit of new shapes, is going to define the design effort for years to come. And any search for meaning always starts with a question.

Clive Dilnot, a professor at The New School University, writes in an essay titled “Ethics? Design?” that the basis of any design activity derives from a fundamental query posed by Socrates: “How should one live?” According to Dilnot, this question cannot lead to a singular answer. Rather, the argument is brought up again and again by every new generation, leaving the ethical dimension of design “always in question, always in doubt.”

It is not surprising that the best design schools are in the forefront of design’s quest for meaning. Unencumbered by market considerations, academia is well suited for experimentation, creative research and the production of ideas. It is good to be a student in times like these. But what about the teachers? The traditional role of all-knowing professor is rapidly changing. Instead, a teacher has become a fellow researcher, a team leader who works with the group in an interactive, collaborative way. The result is inevitably interdisciplinary: a design “product” could be an idea, a service, a material or a narrative, and it is viewed as a process rather than an artifact.

With these thoughts I start a new chapter in my professional life. Recently, I have become director of graduate design studies at the Virginia Commonwealth University in Qatar. All complexities and contradictions on the modern world are reflected in the microcosm of this Persian Gulf state: East and West, old and new, national and global, rich and poor. This is a world in transition, full of its own uncertainties. As such, it should be a great testing ground for new ideas and new solutions. A small group of young men and women from different design backgrounds are joining our program, the first of its kind in the entire Gulf Region. Let the experiment begin. Together, we will be trying to work out our own answers to that nagging question, Why Design Now?

Observed

View all

Observed

By Constantin Boym

Related Posts

Business

Courtney L. McCluney, PhD|Essays

Rest as reparations: reimagining how we invest in Black women entrepreneurs

Design Impact

Seher Anand|Essays

Food branding without borders: chai, culture, and the politics of packaging

Graphic Design

Sarah Gephart|Essays

A new alphabet for a shared lived experience

Arts + Culture

Nila Rezaei|Essays

“Dear mother, I made us a seat”: a Mother’s Day tribute to the women of Iran

Recent Posts

Minefields and maternity leave: why I fight a system that shuts out women and caregivers Candace Parker & Michael C. Bush on Purpose, Leadership and Meeting the MomentCourtney L. McCluney, PhD|Essays

Rest as reparations: reimagining how we invest in Black women entrepreneurs Food branding without borders: chai, culture, and the politics of packagingRelated Posts

Business

Courtney L. McCluney, PhD|Essays

Rest as reparations: reimagining how we invest in Black women entrepreneurs

Design Impact

Seher Anand|Essays

Food branding without borders: chai, culture, and the politics of packaging

Graphic Design

Sarah Gephart|Essays

A new alphabet for a shared lived experience

Arts + Culture

Nila Rezaei|Essays

In 1986, Constantin Boym founded Boym Partners Inc. in New York City. His studio’s designs, many of which are produced in partnership with his wife, Laurene, include tableware for Alessi and Authentics, watches for Swatch, lighting for Flos, showrooms and retail displays for Vitra and exhibition installations for many American museums.

In 1986, Constantin Boym founded Boym Partners Inc. in New York City. His studio’s designs, many of which are produced in partnership with his wife, Laurene, include tableware for Alessi and Authentics, watches for Swatch, lighting for Flos, showrooms and retail displays for Vitra and exhibition installations for many American museums.