Adrian Shaughnessy, Teal Triggs|Exhibitions

December 2, 2014

Graphic Language

.jpg)

Adrian Shaughnessy

: Working on the GraphicsRCA: Fifty Years exhibition and book has given me a deeper understanding of how the past shapes the present, but also how the notion of perpetual revolution—the sense that we have to rebel against the past in order to make the future—is the key to growing a healthy forward-looking institution such as the RCA.Take the discipline of graphic design itself. If we consider the teaching of the subject at the RCA from its beginning in 1948, we see the repeated framing of the question—what is graphic design? The question was posed in the postwar era when the department was formed to cater for a new era of industrial and technological progress; it was asked again in the DayGlo blaze of the pop culture revolution of the 1960s; it was posed in the 1970s and 80s, as the increasing professionalization of graphic design threatened to obliterate avant garde trends; and again in the 1990s and into the new millennium, when graphic design moved into the digital dimension and acquired the postmodern trait of unyoking itself from traditional norms. And it is still asked today. But each time the question is asked, a different answer comes back. In your opinion, is this healthy? And are there constants – things that don’t change? Things we should hang onto?

Teal Triggs: I agree that GraphicsRCA: Fifty Years, overall has been an extraordinary experience in that it provides a rich source of material from the College and School-based archives through which we have been able to explore with current students, staff, and alumni as to what graphic design may have been at the RCA but equally, to speculate about its future possibilities. It has been an unique privilege to be able to be able to be immersed in an extraordinary archive of student work beginning in 1948 to the present, with the goal of better understanding the historical journey of a group of students over time; but also how their work has impacted or been influenced by the broader social, political, and production contexts. One does not sit independently of the other. So whilst the catalyst may be revolution, I would also argue it is also about an evolution as integrally linked to the shifting paradigms around design and the contexts in which it operates.

Richard Guyatt, who was appointed in 1948 as the first professor of Graphic Design at the RCA, introduced a vision of the art school as fostering a “life-long journey of self-discovery.” This could also describe the evolution that graphic design has undergone over the last fifty years, both as a profession and as a taught discipline.

AS: You raise a provocative question—how do we teach graphic design in a way that is “fit for purpose”? Especially when, as you also note, there is no longer a single definition for graphic design—an increasingly multi-dimensional, fluid and borderless activity. I came across a quote by the designer James Goggin, an RCA alumnus and now based in the US, that captures the new maturity in graphic design: “Graphic design,” he states, “now occupies a position where it should be confident enough as a discipline to be both a vehicle for fulfilling social needs and for expressing independent thought. A discipline equal to art, not aspiring to art.”

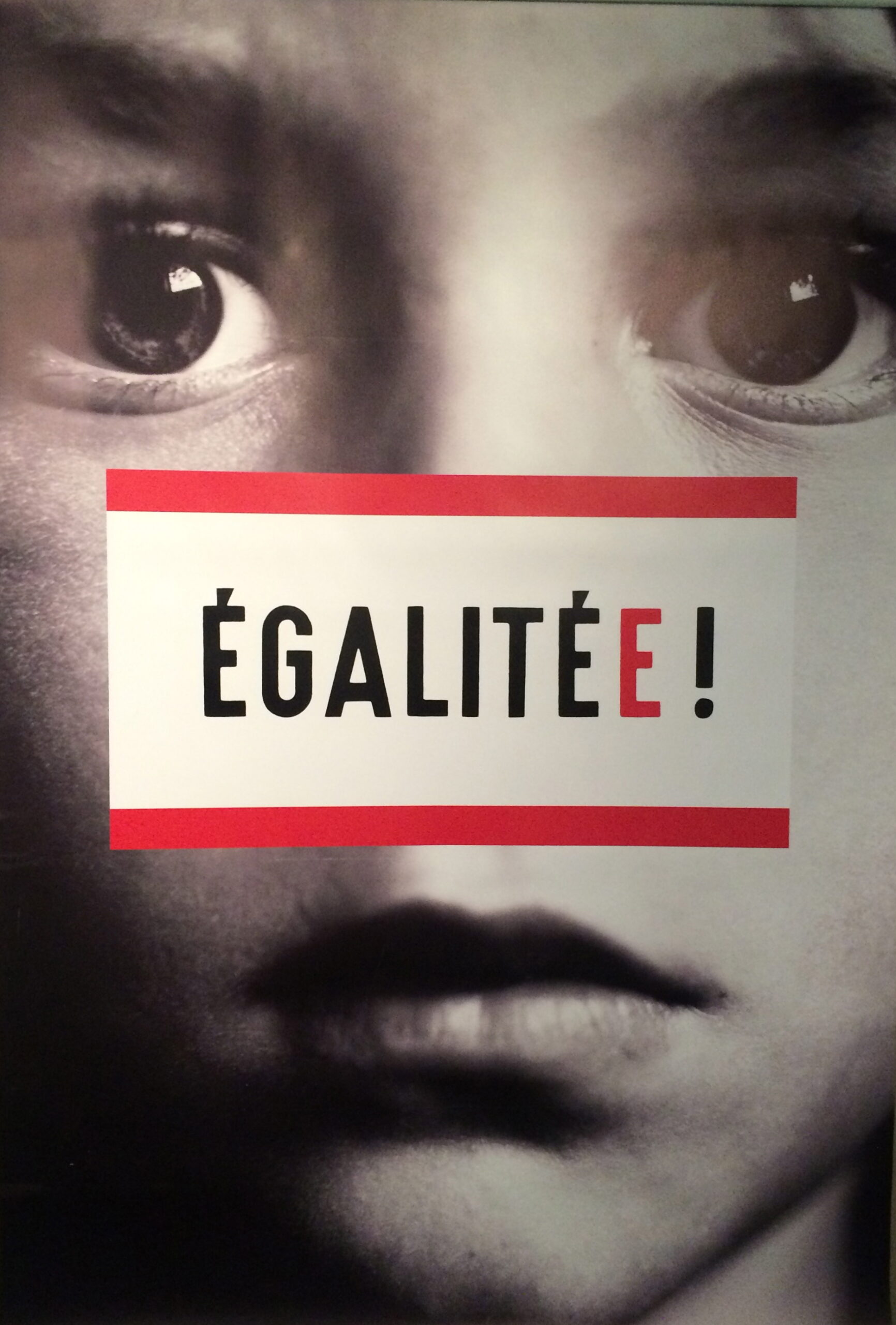

Kristin Matthews and Sophie Thomas (RCA: 1995–1997), Recycle and Reuse, poster

Coincidentally, this is a view remarkable similar to one expounded by Richard Guyatt in 1974. “I do not subscribe to the current view,” wrote Guyatt, “that one can separate the fine arts from design. For me the sparking point of interest in both these areas is the art with which they are practised. There’s such a thing as the art of painting, and there’s such a thing as the art of designing, and sad it is for either if art is absent—as it is so often.” He also made the startlingly contemporary observation that “ … there is a growing awareness of the social role of the designer, a genuine wish to be of service to the community in a worthwhile way.” Both of these statements were unfashionable in the in the 1970s, and both seem to have a strong resonance amongst our current graphic design students who draw liberally from art theory and who also wish to apply design skills to social issues.

TT: Ah—you got me! You are right that the word “teaching” is perhaps not quite right as a term for what we do in general. However, in my defence, I was using “teaching” in a much broader sense; the RCA is a university and as such, a place where learning and teaching is undertaken. It is no accident that as a wholly art and design postgraduate institution, we place the term “learning” before that of “teaching.” I would also venture to say that the context of the art school, and all that brings to an ethos of “teaching” is important.

Damon Murray, Stephen Sorrell, Peter Miles (founders of FUEL; RCA: 1990–1992), Everything Everywhere is for Sale, poster

AS: This is the killer question. Oddly, in the days when I ran a studio, I hired a number of graduates from the RCA and they were all wonderful, in their different often-contrary ways. Not always easy and certainly not oven-ready studio fodder. They all possessed the “autonomy” gene, which while it was an admirable quality, wasn’t always the most helpful asset in a professional context. Ultimately, however, everyone I employed from the RCA went on to form their own studios. And I suppose if you encourage a critical frame of mind—what Neville calls “dangerous minds”—independence really is the only option.

TT

: I think your point about RCA graduates embracing an “expanded practice” is a good one, and often the opposite of many masters’ level programmes which tend to offer students a more subject specialist education. The RCA provides a framework that is “expandable” in that it broadens out the student experience—especially in the first year (of a two-year course), whilst also encouraging a deeper engagement through methods of research, critical engagement and the process of making. I think this approach fosters the ability (and confidence) to move inside and outside of the subject with some ease. This explain one of the reasons as to why a large proportion of our graduates go on to be involved in some capacity as teachers. So it comes full circle for me: “Head, Heart, Hand”—I believe are also the attributes of not only a holistic designer, but also a holistic educator.

Observed

View all

Observed

By Adrian Shaughnessy & Teal Triggs

Recent Posts

Minefields and maternity leave: why I fight a system that shuts out women and caregivers Candace Parker & Michael C. Bush on Purpose, Leadership and Meeting the MomentCourtney L. McCluney, PhD|Essays

Rest as reparations: reimagining how we invest in Black women entrepreneurs Food branding without borders: chai, culture, and the politics of packaging