September 20, 2010

In Search of Sukkah City

This was originally published on June 9, 2010, and is republished today on the occasion of the opening of Sukkah City exhibition in Union Square, New York City.

Among the most beautiful uses of design as metaphor is by the theologian Abraham Joshua Heschel, in which he compares the intricate desires and distinctions of the Sabbath to those of a building: “Judaism teaches us to be attached to holiness in time…to learn how to consecrate sanctuaries that emerge from the magnificent stream of a year. The Sabbaths are our great cathedrals…” Jewish ritual, he adds, “can be characterized as the art of significant forms in time, as architecture of time.” The holiest location in that magnificent stream is not a space, he notes, but a day. The design is in the moment, not the room.

Almost all spiritual or ritual observances have their calendars, but Heschel, in his book on the subject, deliberately aligns shabbat with cathedral: both structures grounded in the everyday, yet just a shiver beyond it. The metaphor works because a cathedral in space is also mostly a cathedral in time: we are aware of the building’s great age; of the startling tactile and visual immediacy of its ancient materials; of the simultaneous heaviness and lightness of stone and glass; of numinously recursive acoustics that turn a mere cough-and-chair-scrape into the flutter of an angel’s wings. We are aware that the grandchildren of those who laid its foundations may not have lived to see its highest spires; and aware that something of this time-out-of-time slowness coolly enters us when we enter it.

So what, for architects and other theologians, is to be made of an almost opposite ritual structure with which Heschel would also have been familiar: the very temporary, forcefully cheerful and sometimes ramshackle, little pavilion or spare room that is constructed for one week out of the year in observance of the Jewish harvest festival of Sukkot? What is to be made of the sukkah?

This question is prompted by Sukkah City: NYC 2010, a design/build architecture competition that I’m working to organize in partnership with journalist Joshua Foer. We’ll be supporting and awarding the construction of a dozen experimental pavilions in Union Square Park in New York City this Fall, which will explore how the very old questions that the sukkah inspires can be answered in very new ways — pushing the possibilities of deployed (pre)fabrication, craft, and material practice that a temporary structure inspires.

So what is this structure, exactly? The sukkah suffers a bit. It can be homely as well as homey: that name sounds almost irresistibly like sucker. Sukkot, the Hebrew plural of the term that names the holiday it embodies, doesn’t do much better, (especially as I first heard it half a lifetime ago, in the harsh bleat of Boston’s inner suburbs, accented to rhyme with dammit.) The conventional translation, Festival of Booths, sounds, frankly, like the worst festival ever. Yet perhaps among all the booths of the world — phone, clerk, toll, isolation, voting, confessional, peep-show, carnie — only photo, with its light-hearted intimacy and anticipation, its sitting-closely-together and making-something-lasting out of a fleeting moment, conveys a hint of the sukkah’s design intention. In the annual cycle, Sukkot represents a homecoming and grounding after the solemn excursions and elevations of Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement: starting to build your household or community sukkah is one of the first actions to which you apply your theoretically lighter conscience. It’s a harvest festival, with all the attendant bittersweet autumnal melancholy of such a time. But it’s also traditionally a feast of bounty, of hospitality, of welcome strangers, of ambitious food and uncellared wine, of unprofessional singing under a fat full moon.

By some interpretations, in one of the sukkah’s many paradoxical possibilities, you’re actually commanded, when inside, to rejoice. Traditionally, you eat, sleep, study, and otherwise dwell as much as possible within the sukkah throughout the week during which it stands. This temporary dwelling is said to commemorate, among other things, the improvised shelters historically built in fields during harvest. Biblically, it is reminiscent of the tents and other phenomena that functionally or figuratively provided shelter during the forty desert-wandering years of Exodus.

But it’s as a design assignment that the sukkah unfolds into something remarkable. There are conventional contemporary types, like a perimeter assembly of standard 4×8 plywood panels with pine boughs above, or a boxy prefabricated tent topped by bamboo mats. But as a continuous work of architecture, the sukkah has persisted across centuries not as a typology — nor as a landmark, a monument, a ruin, a kit-of-parts, or as any other familiar form of architectural preservation — but as a conversation. And as a resulting array of interlinked parameters. These have accumulated as a historiographical record of debates and distinctions developed by generations of scholars and theologians, that, taken together, read like something between a civic zoning code and a beat prose poem. Some parameters, such as whether you can use pre-existing walls (sometimes), or whether you can deploy otherwise useful readymade objects for the roof (never), seem designed precisely to encourage the ephemeral nature of the building. And thus to ensure the permanent effort of its perpetual reconstruction.

Other parameters seem more straightforward: The essential elements are an overhead condition of some kind of foliage, (i.e., non-food botanical, ground-grown leaves? branches? grasses? flowers?) arranged with an intermediate porosity providing daytime shade and nighttime starlight; and a geometry of exposure/enclosure that engages the balance suggested by a consensus minimum of two complete “walls” and a third incomplete “wall”. But God, as usual, is in the details. Or at least Math is: the historiographical record includes tight indications about the distance between walls when they’re in certain geometrical relationships, about maximum gaps between components such that they can still be said to relate to each other with the language of “ground”, “wall” and “roof” — often measured, gratifyingly, in Biblical handbreadths and cubits. A thoughtful project could be extrapolated from any one of these commentaries on intersection and adjacency — although they all beg the question of what really is a wall, or “wall-ness” when disassociated from any preconceived form or tectonic role. A debate about how much the wall of a sukkah can move in a continuous wind, and still be considered a wall, suggests similar extrapolations. Further parameters are more no-nonsense: don’t build a sukkah under something that blocks the sky overhead; make it big enough, at its smallest, for one person to sit on the ground and eat (27 inches by 27 inches by 38 inches, to be precise), but don’t make it so tall (30 feet, apparently), that when you’re inside, you don’t really feel like you’re inside. And so on.

So there are rules. And design, that familiar dance between limits and liberties, thrives with rules that it can simultaneously reinforce and resist. We’re accustomed, as architects, to punch-lists and programs that tell us the minimum deliverables. And when we’re thinking about the encounter between religious observance and domestic life, we’re accustomed to thinking in terms of prohibitions — the closest adjacent model being the milk-and-meat dietary restrictions and kitchen segregations of many religious traditions, including Judaism. And it’s true that the parameters of the sukkah, derived ultimately from descriptions and injunctions in the Bible’s book of Leviticus and other substantial texts, do carry for many a lawfulness of practice far heavier than, say, the folkloric traditions of a Christmas Tree.

Yet when we look closely at the parameters that describe and define a sukkah, we see that they are neither exclusively prescriptions nor prohibitions. Many of them are surreal speculations about possible “limit conditions.” What circumstances must have inspired the ancient debate about whether it’s okay to adaptively reuse the side of an elephant as a sukkah wall? (Apparently it is, although the surprising operative variable is whether the animal’s height and posture are subject to change.) There’s a documented consensus that, with certain caveats, it’s okay to use a whale to make a sukkah. Or to build a sukkah on top of a camel. Or on a boat. Or, seemingly impossibly, on top of another sukkah.

One way to live is to think carefully through every possible contingency and decide in advance what is the correct response. Another way is to try to locate very clearly your best intention, and then just wing it. And maybe pray. Some of the seeming parameters of the sukkah seem more like this. They are invocations rather than injunctions: it should draw one’s attention upwards; it should inspire joy.

Furthermore, precisely the parameters that seem least subject to interpretation are the ones that establish a lived experience of speculative indeterminacy. If the roof is not exactly solid, as it must not be, then exactly how inside are you, when you are inside a sukkah? Are you in the natural world or the man-made? How is the same overhead condition supposed to feel more enclosed during the day, and more exposed during the night? If the perimeter is not entirely continuous, as it must not be, then how does it establish a sense of here and there? Is there a threshold? Are you at home or are you far away from home? The strictest rules of the sukkah seem to be the ones that establish conditions of indeterminacy, of in-between-ness; of the thrill and peril of possibility.

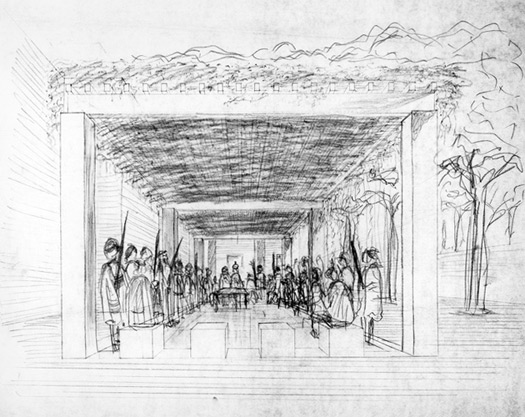

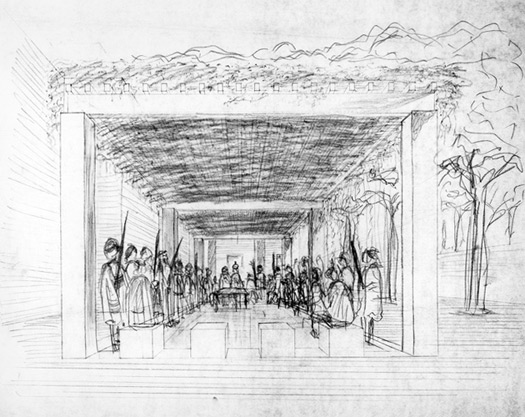

Louis Kahn, an architect who like Heschel knew a little something about how cathedrals work, designed a modern sukkah in the 1960s. It was among his unbuilt projects for Philadelphia’s Mikveh Israel congregation. His drawing for it is charming, but at first glance a little dull: a kind of boxy pergola vaguely recalling in its heavy uprights the pavilions deployed in the canonical 1959 Trenton Bathhouse project. But the more you look at the drawing the weirder it gets. The lines deployed to describe the cut foliage resting on a roof screen continue unbroken into those outlining the crowns of adjacent living trees; the lines lightly suggesting floating fabric curtains blend indeterminately into those suggesting the solid walls of the adjacent building; even the marks indicating bodies of people inside the sukkah scintillate somewhat, in a Where-the-Wild-Things-Are-like flicker, into those indicating tree trunks and columns. So, somehow, the more one is drawn into the interior of this sukkah, the more one is drawn into the world that surrounds it.

All architecture, at its most effective, should do this. The sukkah, in its radically temporary way, is different only by degree, not kind, in its embodiment of this mission. It expresses an aspiration of design to create a bridge between seen and unseen worlds; between eternal, elemental, and ephemeral; between the social or natural conditions to which we’re accustomed, and those that surround us, often invisibly. My most lasting memory of an evening in a sukkah is bittersweet in this way. Somewhere between drinks and dinner, a perhaps unwisely romantic candle that was part of the intricate decoration of the structure, sent a ferocious flame across the fabric walls and tinder-dry roof. In a heartbeat, half the sukkah was gone. By some combination of fortune and quick-thinking, no one was hurt and the fire was put out. But we had a sukkah that was one half glittering gypsy caravan, and one half smoke and wet ash. We had dinner ready. We had an infinite moment in time before our sassy hostess said, to hell with it, and dragged out a long table that bridged both halves, and served the food and wine. I remember thinking, sitting down at the ash end, maybe this table is what a sukkah is: something that you build and rebuild, that bridges what it means to dwell in glory, and what it means to sleep in dust.

Sukkah City: NYC 2010Â will re-imagine this ancient phenomenon, develop new methods of practice and design, and propose radical possibilities for traditional design in a urban site. Twelve finalists will be selected by a panel of architects, designers, and critics to be constructed in a village in Union Square Park from September 19-21, 2010. One structure will be chosen by New Yorkers to stand throughout the week-long festival of Sukkot as the Official Sukkah of New York City. Sponsored by Reboot and Union Square Partnership. Entrants must register by July 1 and submit entries by August 1. Design Observer Group is proud to be a partner of Sukkah City.

Observed

View all

Observed

By Thomas de Monchaux

Recent Posts

Minefields and maternity leave: why I fight a system that shuts out women and caregivers Candace Parker & Michael C. Bush on Purpose, Leadership and Meeting the MomentCourtney L. McCluney, PhD|Essays

Rest as reparations: reimagining how we invest in Black women entrepreneurs Food branding without borders: chai, culture, and the politics of packaging

Thomas de Monchaux, the inaugural winner of the Winterhouse Award for Design Writing and Criticism, is currently working on Food Money Sex Style Art Stone Glass, a biography of the building at 2 Columbus Circle, New York.

Thomas de Monchaux, the inaugural winner of the Winterhouse Award for Design Writing and Criticism, is currently working on Food Money Sex Style Art Stone Glass, a biography of the building at 2 Columbus Circle, New York.