If you look closely at the album cover of the Beatles’ St Pepper’s Lonely Heart’s Club Band you can see Lewis Carroll standing behind Marlene Dietrich and within shouting distance of Bob Dylan. Carroll, the author of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, which was published 150 years ago this year, looks at home in this phantasmagorical lineup, where it wouldn’t be out of place to see a large blue caterpillar, sitting on a mushroom, smoking a hookah.

Our fascination with Carroll, and the world he invented, verges on obsession. This autumn sees the publication of a new biography and a gem of an

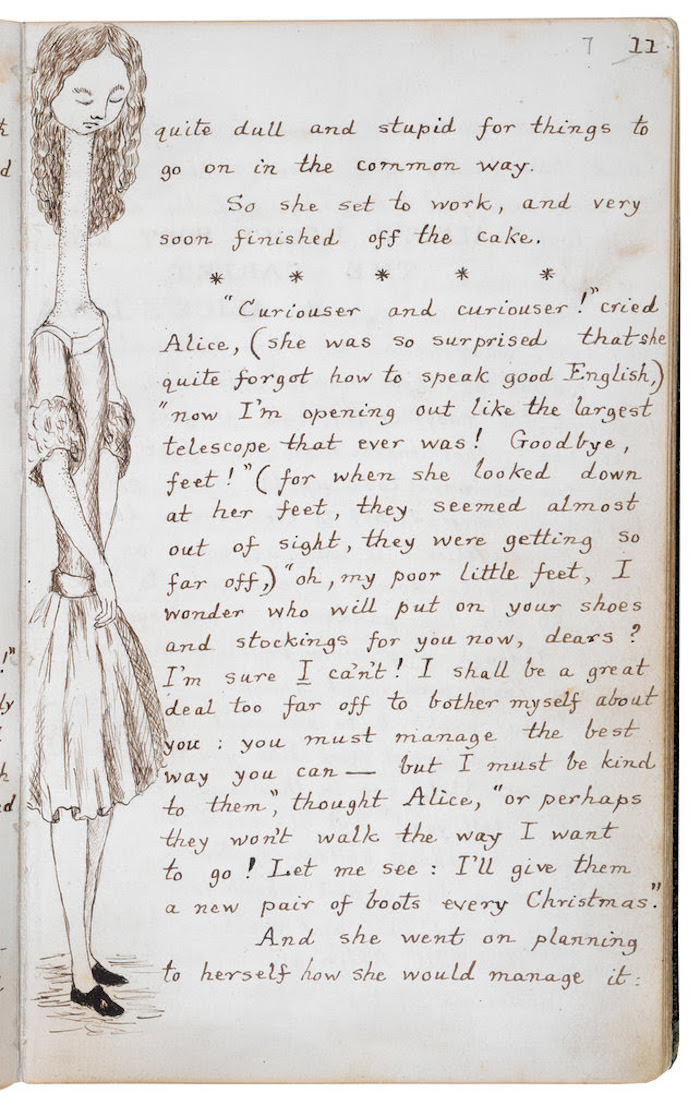

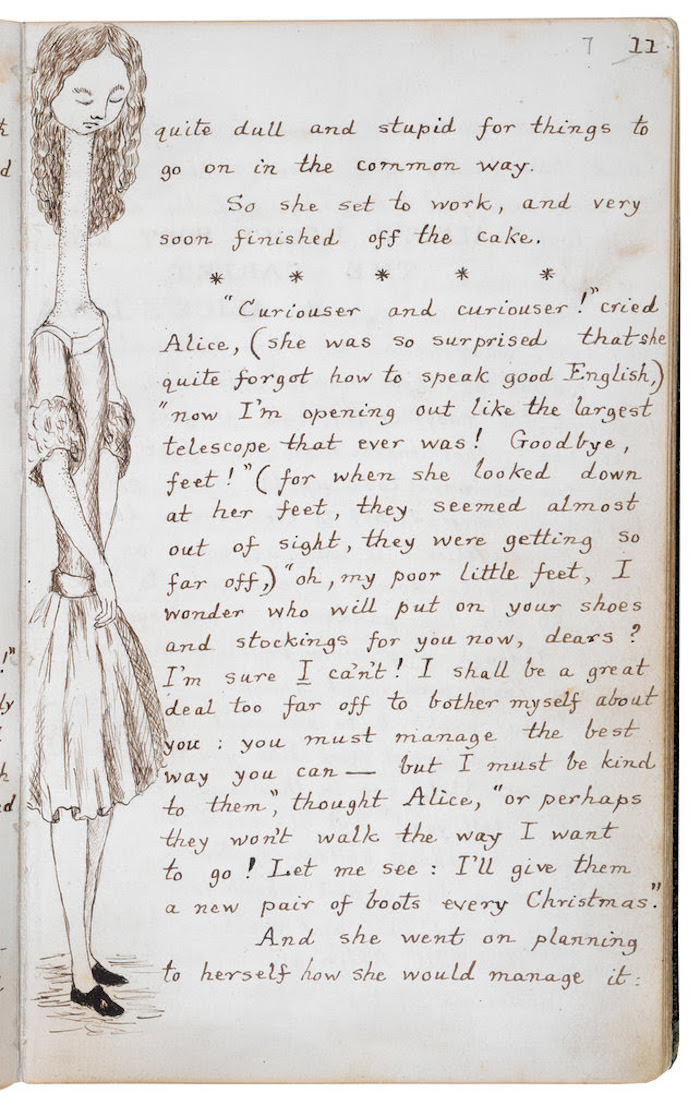

exhibition at the Morgan Library, the centerpiece of which was the original handwritten and illustrated manuscript that Carroll gave to Alice Liddell, the ten-year-old child who was his inspiration and muse.

A handwritten page of the Alice manuscriot; the British Library Board

The origin story of Alice in Wonderland is as follows: on July 4th, 1862, Carroll and his friend Robinson Duckworth rowed the three young Liddell sisters up the Thames for a picnic near the ruins of Godstow Abby. The girls demanded a story, and Carroll, primed for such requests from journeys past, had prepared some skits and songs. But when he began his story he sent his protagonist down a rabbit hole and found himself in new narrative territory, where, he later confessed, he had not “the least idea what was to happen afterwards.”

Carroll photograph of the inspirational Alice Liddell, 1860; The Morgan Library & Museum

The story, with its fragmentary evocation of a Victorian childhood of play-theaters, poems, and puzzles, and nursery room props of cards, gloves, and pocket watches, was the result of inspired improvisation. But the real Alice had already been on a different sort of adventure with Carroll, and it was also in the dark.

It was photography that initially brought Carroll to Alice and Alice to Carroll. He spotted her playing with her siblings in the garden just outside the Christ Church Library at Oxford. He quickly befriended the children (and even marked the occasion in his diary). It was not long after that he began taking photographs of the three girls, but he soon began to focus more on Alice than the others.

Carroll in 1863 with a camera lens; The Morgan Library and Museum.

In 1856 Carroll had bought a colossally expensive Ottewill camera. Over the next twenty-four years he made 3000 wet plate collodion photographs (a vast number in those pre-digital days), half of which were of children (and most of those were of young girls). As Robert Douglas-Fairhurst waspishly writes in The Story of Alice, Carroll viewed the company of young girls as a “little heaven on earth.” When Carroll made a list of the girls he had photographed, or wished to photograph, it ran to 107 names. Heaven was a crowded place.

The process of wet plate photography is exacting, you have to know your chemistry: when to dip the polished glass plate into its bath of silver nitrate, when and how long to expose for, how to develop the image with yet more chemicals, and how to varnish and fix. For the sitter it meant patience and stillness, and Alice seemed to have both. Years later Alice Liddell remembered the experience of visiting Carroll in his darkroom as being “mysterious.” Watching him at work with the glass plates and chemical baths made her feel as if she was partaking in a “secret rite usually reserved for grown ups,” where “any adventure might happen.” She was in another kind of wonderland, where light was dark and dark was light and reality could shrink to the size of a photographic print.

It has been hypothesized that Carroll’s fascination with Alice was in fact a search for his own “lost girlhood”: the pleasures of his childhood spent playing with his seven sisters (there were also three boys). But Juliet Hacking, in her synoptic book, Lives of the Great Photographers, points to a less sympathetic and more predatory reading of his behavior, noting his sustained letter writing campaigns aimed at convincing mothers to allow their girls to be photographed starting first with their bare feet and then, as in the case of a daughter of a fellow Oxford don, progressing to “their favorite state of ‘nothing to wear.’”

It’s tempting to read our post-Freudian understanding of sexuality back onto Carroll and label him a pedophile. Douglas-Fairhurst has a more nuanced interpretation, first noting our need to categorize Victorian sexuality in a manner that conforms to our understanding of childhood today. But in the Victorian worldview there was no fixed idea of adolescence: girls were considered women just after puberty. Before 1865 legal consent was just twelve years old, from 1865 to 1885 it was thirteen. There is no evidence to suggest that he ever behaved in an untoward manner with the girls. More crucially, Carroll might not even have understood his own impulses. “The most probable conclusion is that Carroll strongest feelings were sentimental rather than sexual,” is Douglas-Fairhurst’s empathetic conclusion.

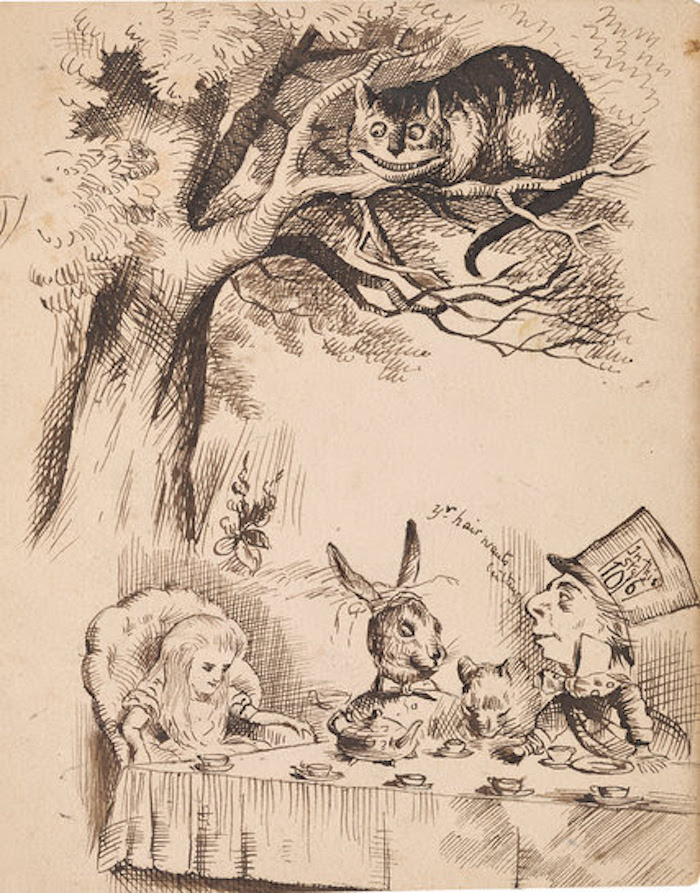

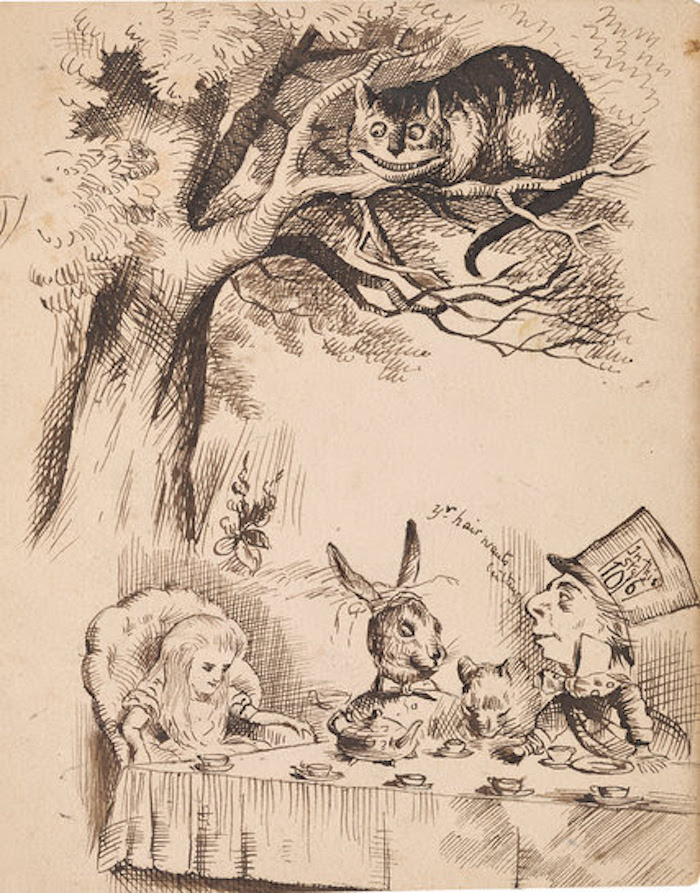

Proof of a Tenniel illustration; The Morgan Library and Museum

The exhibition at the Morgan was a triumph of astute curatorial choices. Rather than a sprawling omnibus of all things Alice, it traced the progress of the book itself, both as a physical object as well as a creative endeavor between Carroll and John Tenniel, the illustrator whose engravings have indelibly given visual form to Carroll’s words. Theirs was a fraught relationship, but it produced a book that Douglas-Fairbanks argues had never been seen previously, a creative combination of words and images, rather than a book where illustrations were merely “prosthetic” extensions of the text. The result was a newly integrated reading experience.

The relationship between Carroll’s photography and his writing, between image and text, is difficult to tease out. Hacking suggests that in both his photographs and his books Carroll subverted the Victorian convention of seeing children as inanimate dolls and in both mediums he gave his (mostly) female subjects individuality and playful agency. It’s a positive spin.

Carroll had a studio and a darkroom in his rooms at Christ Church. There he kept costumes, children’s books, and toys; props for his subjects to construct a theater of their own making, an improvised and inventive world, a world he could then freeze and immortalize in a photographic image. Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland is a more powerful imaginative creation: a place where adult strictures don’t apply, where only the wonderful illogic of dreams reigns: a place where you can drown in a pool of your own tears, break your neck against a low ceiling, or be trampled by a giant guppy. Or where you can watch a cat, sitting on a branch of a tree slowly vanish, leaving behind only a trace of his grin.

A Lewis Carroll drawing of the Mad Tea Party, copied from Tenniel; private collection.