April 21, 2009

Invasion of the Neutered Sprites

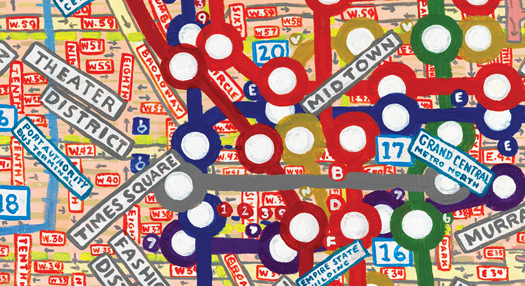

Happy generic figures encircling the world, designer and date unknown

My first paying job as a graphic designer — strictly speaking, as a commercial artist — was doing the illustrations for a filmstrip, one of those slideshows timed to a recorded soundtrack that was popular in mid-20th century classrooms. It was intended to introduce an inner-city youth employment program to potential participants. It was 1975, the summer I graduated from high school. My work was directed by a charismatic black guy whom I now picture as Idris Elba. Nearly 35 years later, I can only remember two things about that project. First, the soundtrack he had picked was the very hip-to-me “Maiden Voyage” by Herbie Hancock. Second, and more importantly, I had a lot of trouble figuring out how to draw the characters that would represent the participants in this program, whose poses would be used to illustrate the step-by-step requirements of enrollment and successful completion.

My first attempts were ambitious: eyes, noses, hairdos, clothing. Idris was patient. “Listen, you’ve got to simplify these. I don’t want people distracted by these hats and stuff.” I tried again. “Better, but can you make it so you can’t tell whether they’re black or white?” Okay, one more time. “Look, Mike, I don’t want people even to know whether these are men or women. They just have to look like…people, you know?” I tried another drawing. Idris was getting antsy. “Right, but these are too stiff looking. Can you make them look a little happier?” Finally I reduced the figures down to their essence: eyeless balls representing heads, atop curvy stars, with the four points representing fingerless, toeless arms and legs. “That’s it!” said my first client.

Without really knowing what I was doing, for my first paying job, I had contributed to a plague: the profusion of sexless, blankly cheerful little people that I have come to call Neutered Sprites. They’re everywhere. Behold!

Representing the archetypical homo sapiens isn’t easy. Da Vinci’s “Vitruvian Man,” from around 1490, was the artist’s attempt to map a kind of universal humanity, but it’s anything but: white, muscled and long-haired, he looks too much like Owen Wilson to serve as a placeholder for most of the world’s population, or at least for me. Over 350 years later, Le Corbusier’s Modulor comes a lot closer. But it’s still undeniably, even militantly, masculine, a strident standard-bearer for the modernist utopia.

Otto Neurath, “Home and Factory Weaving in England,” from Modern Man in the Making, 1939

The quest for a completely neutral approach to human representation led other mid-century designers to pure geometry. Trained as sociologist and political economist, Otto Neurath created a language of symbols called Isotype to convey complex statistical ideas in a simple visual way. There’s no mistaking the gender of Neurath’s square-shouldered, round-headed figures: he frankly calls them “man symbols,” fitting the title of his masterwork, Modern Man in the Making. But they are undoubtably landmarks, and clearly progenitors to the now-ubiquitous bathroom symbols formalized by Roger Cook and Don Shanosky in 1974 as part of the AIGA-led U.S. Department of Transportation Symbol Signs program.

Henri Matisse, Icarus (Icare) from “Jazz,” 1943-44

The design world, however, clearly had a need for a less rigid, “friendlier,” way of representing people. Hence, starting in the late fifties, the rise of the Neutered Sprites. I suspect that many of those who draw these have a vague image in their minds of the dancing figures in Henri Matisse’s collages. These have all the characteristics for which one seeks in vain in Corbu and Neutrath. They are nimble, lively, happy. They are not obviously young or old, black or white, male or female. And one last thing, which is the best of all. Drawing the human figure, as anyone who has taken a life drawing class can testify, is difficult. Neutered Sprites are — or at least they appear to be — really easy to draw. I remember realizing that with great relief back on that very first job. The little bastards just came pouring out of my felt tipped pen, one after another. “Hey,” I thought to myself. “This isn’t going to take that long after all.”

The traditional habitat of the Sprites today, of course, is Nonprofitland. Finding them isn’t hard. Look for logos for organizations dedicated to community-building, or health-supporting, or any kind of relentlessly positive thinking. There you will find these little figures by the dozens, prancing around, holding hands, embracing their families, and generally celebrating the universal themes of wellness, happiness, and goodness.

Unfortunately, they have come to have the opposite effect on me. They make me sour and depressed, not least because of my dim memories of having personally contributed to their proliferation. So, I hereby take a sacred pledge: with Da Vinci, Corbu, and Otto Neurath as my witnesses, I swear I will never create another Neutered Sprite. I invite you to join me. Together, we can defeat this epidemic!

Research assistance by Kai Samela and Rishi Sodha

Observed

View all

Observed

By Michael Bierut