April 9, 2007

Koolhaas and His Omnipotent Masters

Central Chinese Television (CCTV) Headquarters, April 2008. Photo by Jakob Montrasio

According to Rem Koolhaas, there are three seminal events in the history of architecture: Samson tearing down the house of the Philistines in 1100 BC, the destruction of the World Trade Center in 2001 AD, and his design in 2006 AD of the CCTV Headquarters in Beijing. Obviously, this is a reductionist view of history — and the kind of hyperbole one expects from a manifesto in Wired Magazine. But this is no manifesto: instead, as Koolhaas himself recounts the story, he chose between working on NYC’s Ground Zero and the Beijing project based on a fortune cookie he was given at a Chinese restaurant — in it, the goofy prognostication “Stunningly Omnipresent Masters Make Minced Meat of Memory.”

The story of a single cookie presaging the most important building in China is, quite simply, bizarre. It may be a romantic notion, but most of us still want to believe that great architecture is made on a napkin, the source of inspiration being anything except hard work. (According to Paul Goldberger, the design of Koolhaas’s Seattle Public Library can be traced to a single diagram.)

The idea that one of the world’s leading architects would glorify “making minced meat of memory” is beyond comprehension.

Rem Koolhaas, illustration (reconfigured) from the “Beijing Manifesto,” Wired Magazine, 2007.

But manifestos often sound like nonsense. As Allan Chochinov of Core77 has written, they often “reek of dogma and rules. …they appear (or are written so as to appear) self-evident. This kind of a priori writing is easy, since you simply lay out what seems obviously—even tautologically—true.” The Beijing Manifesto of Rem Koolhaas is no exception:

In the free market, architecture = real estate. Any complex corporation is dismantled, each unit sequestered in place. All media companies suffer a subsequent paranoia: Each department — the creative department, the finance department, administration, et cetera — talks about the others as “them”; distrust is rife, motives are questioned. But in China, money does not yet have the last word. CCTV is envisioned as shared conceptual space in which all parts are housed permanently, aware of one another’s presence — a collective. Communication increases; paranoia decreases.

It’s one thing to build the building. But isn’t Koolhaas sounding like an apologist for the corruption and extreme capitalism of Beijing? His manifesto seems to embrace the language of Mao for a media conglamerate that is one of the the great powers in the People’s Republic of China, and the source of much of the censorship in that country. According to Koolhaas’s thesis of Forward Compatibility: “China is characterized by the need to spread opportunity and information rather than protect manufacturers and other established interests. It could use its dominant position, the force of its numbers, its economic power, and its central government to lead the world into a digital future.” What would lead an architect of Rem Koolhaas’s standing to voice such propaganda? Perhaps Koolhaas is simply taking advantage of the pervasive authoritarianism that is still the Chinese norm. Design approvals? No problem, when everyone serves at the pleasure of the Party! He almost seems to be luxuriating in the absence of the nuisance of the free market.

Sadly, his apologia seems vaguely reminiscent of the post-WWII trompe l’oeil of Leni Riefenstahl: the heroic language necessary to justify heroic art. “In communism, engineering has a high status, its laws resonating with Marxian wheels of history.” It’s easy to get lost in, or angry at, such Wired-Magazine-grandiloquence. Or as Paul Goldberger observes, “Koolhaas has always been a better architect than social critic.”

There are numerous examples of Koolhaas producing flawed social commentary to rationalize his architectural conclusions. George Packer, a seasoned on-the-ground journalist writing in The New Yorker, tells of Koolhaas visiting Lagos, Nigeria with his Harvard graduate students. They were all so terrified by the chaos, degradation and poverty that they were incapable of getting out of their cars (undoubtedly Range Rovers), or leaving their hotel for any length of time. Only by flying over the city in a helicopter (rented from the Nigerian president) were they “granted a more reassuring view” — at which point Lagos was deemed to be splendid as an urban model. As Packer observes, “The impulse [by Koolhaas] to look at an ‘apparently burning garbage heap’ and see an ‘urban phenomenon,’ and then make it the raw material of an elaborate aesthetic construct, is not so different from the more common impulse not to look at all.”

The truth, though, is that the CCTV building is stunningly beautiful. End of story — except that Koolhaas didn ‘t stop there. And here, the architect — master of rhetoric that he’s become — asks the very question that most confounds his critics. “Was it merely a landmark, one more alien proposal of meaningless boldness? Was its structural complexity simply irresponsible?”

OMA in Beijing exhibition, MoMA, 2006. Photograph by Iwan Baan.

In the OMA in Beijing exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the viewer is overwhelmed by the sheer magnitude of the CCTV enterprise. “A selection of architectural drawings from MoMA’s collection will situate the project as one of the most visionary undertakings in the history of modern architecture.” Whew! So from MoMA we get outright hero worship instead of any type of critical dialogue. And The New York Times reviewed the exhibition with a fawning piece by Robin Pogrebin titled, “Embracing Koolhaas’s Friendly Skyscraper.” (One is reminded, of course, that neither MoMA nor The New York Times Company selected Koolhaas for their own New York City headquarters.) The most striking curatorial intervention in the MoMA exhibition is the inclusion of the famous Mies van der Rohe drawing, Glass Skyscraper, elevation study, 1922. Koolhaas has aligned himself with Mies van der Rohe for a long time because he was the most modern of the moderns: reductive, universal, abstract. Koolhaas even speaks of “a return of Miesian Puritanism about steel.”

The CCTV building has now reached fourteen stories, and we can easily anticipate the photographs of Chinese workers scaling the steel structure, much like the Lewis Hine photographs of steel workers building the Empire State Building, mostly Mohawk Indians “known for their agility and courage in working on steel beams far above the city below.” So far, however, most of the construction photographs we see are devoid of workers, steel being the hero. (“Quite impressing amount of cranes and steel” [sic] reads a typical photo caption.)

Maybe the real hero worship around Koolhaas’s architecture should be reserved for the engineers who have poured so much steel into this structure. For perspective, the World Trade Towers (completed 1970-72), each with 110 floors, required 200,000 tons of steel for 13 million square feet of space, or 31 lbs/sf of steel.

CCTV, at only 55 stories, requires 123,750 tons of steel for 4.8 million square feet of space, or 51 lbs/sf of steel. The punch line is that CCTV is the architectural equivalent of a gas-guzzling SUV. A structural engineer might talk about pounds of steel per square foot as a measure of a building’s structural efficiency. CCTV has a beautiful structural design considering what it is required to do, but any engineer, I believe, would describe it as a “heavy” building. By comparison, the World Trade Towers were a super tall, extreme structure and they were still 40% lighter than CCTV. There is a lot of extra steel (20 to 30 lbs/sf) in the CCTV structure simply to resist overturning because of the weight and stress of its free-floating bridge, even assuming contemporary code and seismic requirements.

The issue is simple: all this steel is there to support a design conceit, albeit a beautiful one, of “an eye catching megastructure which looks like it ought to fall over.” Rory McGowan, the ARUP director of the collaborating structural engineers, “admits that the structural gymnastics have a purely aesthetic justification.”

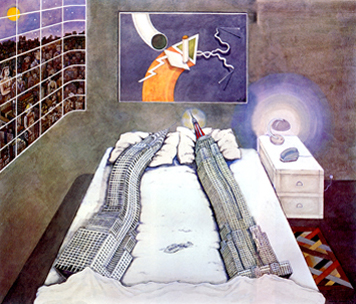

Madelon Vriesendorp, Après l’amour, c.1976. From Delirious New York by Rem Koolhass, 1978.

Much can be said of the architecture of Rem Koolhaas. It can be “raw, confusing, impersonal, uncomfortable, oppressive, theatrical and exhilarating.” I keep coming back to the word, “exhilarating.” It has been that for me since I saw the Empire State Building post-coitus with the Chrylser Building in his first U.S. exhibition at the Guggenheim in 1978. I just wish “the most visionary undertaking in the history of modern architecture” had strived for something more than a bridge of steel in China.

In the end, all the political discourse and self-serving manifestos mean little. We are left to judge this building as a piece of architecture built in 2007, in a climate of growing awareness of sustainability. Building a project of this scale with so much extra steel to support an aesthetic expression seems like a missed opportunity, if not something completely bordering on civic negligence, especially in China, one of the countries which necessarily must embrace sustainability soon. Imagine if Koolhaas had used this opportunity to build the lightest, most green building in the world? Imagine if he had marshalled all of his rhetorical verve and diplomatic savvy to argue for the critical importance of such architecture? Instead of responding to fortune cookies, Rem Koolhaas could have changed the world.

Observed

View all

Observed

By William Drenttel

Related Posts

Business

Courtney L. McCluney, PhD|Essays

Rest as reparations: reimagining how we invest in Black women entrepreneurs

Design Impact

Seher Anand|Essays

Food branding without borders: chai, culture, and the politics of packaging

Graphic Design

Sarah Gephart|Essays

A new alphabet for a shared lived experience

Arts + Culture

Nila Rezaei|Essays

“Dear mother, I made us a seat”: a Mother’s Day tribute to the women of Iran

Recent Posts

Minefields and maternity leave: why I fight a system that shuts out women and caregivers Candace Parker & Michael C. Bush on Purpose, Leadership and Meeting the MomentCourtney L. McCluney, PhD|Essays

Rest as reparations: reimagining how we invest in Black women entrepreneurs Food branding without borders: chai, culture, and the politics of packagingRelated Posts

Business

Courtney L. McCluney, PhD|Essays

Rest as reparations: reimagining how we invest in Black women entrepreneurs

Design Impact

Seher Anand|Essays

Food branding without borders: chai, culture, and the politics of packaging

Graphic Design

Sarah Gephart|Essays

A new alphabet for a shared lived experience

Arts + Culture

Nila Rezaei|Essays