Sarah Handelman|British Telecom, Essays

November 15, 2011

[MB][BT] Shorthand Science and Magic Lessons

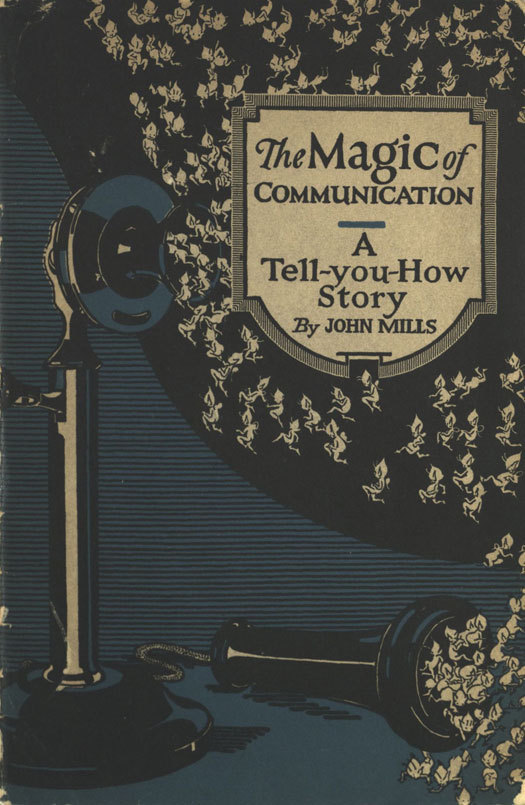

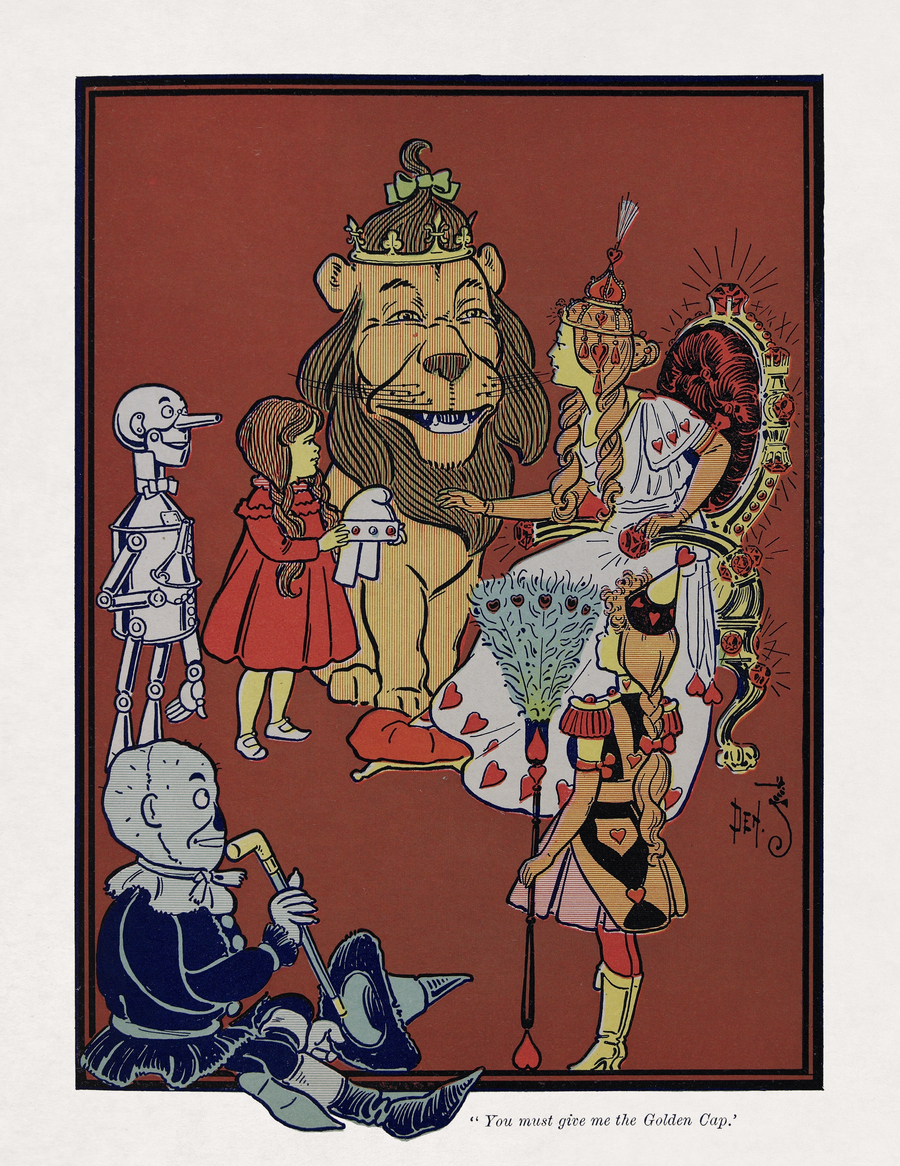

The cover of The Magic of Communication. Published in 1926 by the information department of AT&T, the pamphlet employed the popularized idea of enchantment to educate consumers on the science of telephony.

BT is the world’s oldest communications company, with a direct line of descent from the first commercial telecommunications undertaking anywhere. The below essay is one of seven, the result of a collaboration with Teal Triggs and Brigitte Lardinois from the University of the Arts London and their students in the Design Writing Criticism program.

There are fairies in your phone. There is a book of magic at BT Archives. Open it up, and discover that the molecules aren’t what they seem.

Situated between neatly catalogued books eager to provide ordinary lessons in telephony, the slim volume is rendered nearly invisible by an unmarked spine. With a tug, it slides out to reveal an unexpected lesson in telephone use: Electrons march. Atoms dance. Operators become gatekeepers to telephone cities. The Magic of Communication brims with possible impossibility.

Published in 1926 by AT&T, The Magic of Communication draws on the popularity of 1920s enchantment to tell the information story of telecommunications. The 47-page promotional leaflet blends science and magic to make sense of what is not seen, but heard.

The Magic of Communication is a paradigm of how popular culture is used to enhance informational material. In the 1920s, magic was everywhere: Harry Houdini captivated society with illusions; the Cottingley fairy photographs were worldwide news fixtures. On the leaflet’s cover, Victorian- inspired fairies tumble out of a telephone, making the publication a welcome departure from other informational material of the time. Further down-shelf, the 1925, UK-based Outline of Telephony similarly serves “to give…a succinct yet comprehensive description of the telephone systems at work in the world to-day.” Yet the guide, like other British publications, is too technical in its explanation of telephony to an audience that might not even have had electricity in their homes. However, The Magic of Communication suggests there is an allure to telephony. Subtitled “A Tell-You-How Story,” it reveals that we will be let in on the science — and magic — of phone calls. The AT&T pamphlet demystifies telephony and emphasizes the egalitarian relationship between humans and technology: A telephone call “is started by the voice of the person who is speaking…” One is not possible without the other.

Beyond the cover, the telephone story is introduced with bright-eyed exposition. The author, John Mills, introduces the “History of Human Speech” as if he has sat us by a crackling fire to hear an exciting tale. He writes in charming language that comes closer to fairy stories than textbooks, compelling us to engage in a history lesson without feeling overwhelmed by particulars. “What man has always needed is some method of communication that would enable his actual speech to be heard miles away and only by the particular person addressed,” he writes. “For thousands of years this was so impracticable that it was not even a dream.”

Initially, few concrete facts are provided in the brief history. The first date given is the invention of the telephone, implying that prior historical knowledge is nonessential. Though the history of electricity is told in an enchanting way, the word magic is not written until page five, in a section labeled “The Telephone,” which suggests the fairy tale of telephony lies within the instrument itself: “…It catches the spoken word like magic and turns it into something we cannot see or hear which speeds along the wires to another telephone and there the magic is undone and the hidden word comes forth.”

Using enchantment to explain science isn’t a new idea; behind every successful magic trick is a tried scientific method. In the 1920s, Houdini partnered with Scientific American to expose spiritualists and psychics as frauds. Rather than explain the science of telephony as magic, AT&T makes science magical. For adult consumers, the text has the familiar timbre of a children’s story. While morals and lessons are disguised by adventure in fairy tales, the science — and commercial potential — of telephony is masked by enchanting language that captivates our imaginations and presents information AT&T deems valuable.

If the magician behind telephony is electricity, then the assistant is the telephone operator. In the pamphlet she serves two functions: Textually, she plays a crucial role in Mills’ explanation of how telephone exchanges work. “For every conversation,” writes Mills, “two telephone doors must be opened, yours and that of the person whom you are calling. The operators do this for you.” By suggesting that operators hold the key to the door between caller and receiver, Mills infuses them with an enchanting, good-witch persona. The operators make wishes come true. Secondly, the operator is visually portrayed through illustrations, photographs and diagrams. In the center of the title page she is represented by a delicate line drawing. She possesses all the lovely traits of a princess, and her early appearance in the pamphlet foreshadows her significant role in telephony. Several pages later, the image is replicated in photographic form, as if she were magically brought to life. Before, she was a voice connecting callers; now she has a face, one that fills us with as much wonder as the sound from the exchange. Next to the photograph is a diagram of a switchboard controlled by the operator’s well- manicured hand. Using a pen-like apparatus similar to a magic wand, she opens the jack to create a two- way conversation.

Diagrams are not only implemented to depict the operator. The fairies from the cover are now more than just intriguing images; they expand on Mills’ wonder-filled tone and show how the inexplicable can be understood. In a set of figures illustrating a phone call, molecules transform into hand-drawn silhouettes of men that dance between telephone wires. Mills himself is an illusionist; he does not simplify the scientific language of the body text and captions. Instead he adds enchanting descriptions to scientific terms, making us wish that all textbooks were this fascinating.

Back on the shelf, the real secret behind the blue-bound book of magic is obvious: it is simply a promotional tool — one that reached a million AT&T customers each year. But compared to the surrounding volumes, The Magic of Communication is an imaginative tome that uses enchantment to enhance our understanding of modern technology. Though we learn there aren’t really fairies in our phones, being in on the science and the magic of communication is, in itself, enchanting.

Observed

View all

Observed

By Sarah Handelman

Related Posts

Innovation

Ashleigh Axios|Essays

Innovation needs a darker imagination

Business

Kim Devall|Essays

The most disruptive thing a brand can do is be human

AI Observer

Lee Moreau|Critique

The Wizards of AI are sad and lonely men

Business

Louisa Eunice|Essays

The afterlife of souvenirs: what survives between culture and commerce?

Related Posts

Innovation

Ashleigh Axios|Essays

Innovation needs a darker imagination

Business

Kim Devall|Essays

The most disruptive thing a brand can do is be human

AI Observer

Lee Moreau|Critique

The Wizards of AI are sad and lonely men

Business

Louisa Eunice|Essays