November 18, 2009

Metabolic Dark City

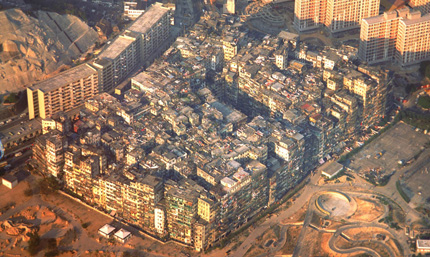

In 1993, the City of Darkness, or the Walled City of Kowloon, was demolished. To the 35,000 people living in this dense urban slum, the change was the end of a lawless existence. The area was a diplomatic black hole, the model of an anarchist society somehow allowed to grow organically without the aid of any government, existing somewhere outside of both British Hong Kong and China.

The buildings of “Hak Nam” folded into one other in a dense configuration of labyrinthine corridors and seedy brown shacks stacked up 10, 12 and 14 stories high. It was a solid building, 200 x 100 meters, a pulsating anomaly, one of the most densely populated places in the world at the time of its destruction. It was called “the world’s first flexible megastructure, the closest thing to a truly self-regulating, self-sufficient, self determining modern city that has ever been built,” “an environment as richly varied and as sensual as anything in the heart of the tropical forest.”

One should be wary of any flawed social commentary from architects, such as Rem Koolhaas’ infamous flyover of Lagos, Nigeria. George Packer, in “Megacity: Decoding the Chaos of Lagos,” said, “The impulse to look at an ‘apparently burning garbage heap’ and see an ‘urban phenomenon’… is not so different from the impulse not to look at all.” The reality of the city is this: it is fluid and boundless, an agglomeration of layered fragments of junk and ruins. Old television sets, broken furniture are lugged up to the roof and abandoned. It would be a nightmare for any of us, but what of the people that live there? As documented in City of Darkness by Greg Girard and Ian Lambot, some were able to survive and thrive in Hak Nam. Chui Yiu Shan, for instance, became a property developer and real estate agent who thrived in spite of or maybe because of the lawlessness inside, making $20,000 a month dealing with property transactions.

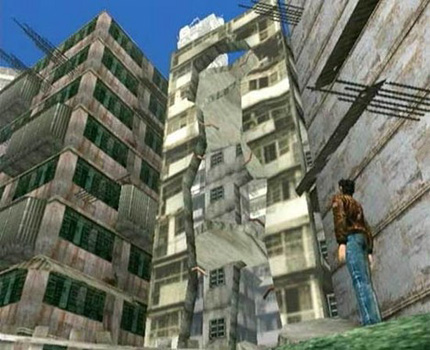

I didn’t experience Kowloon Walled City from a helicopter. In fact, I’ve never been there at all, and now I never will, of course. But I have simulated the experience with the help of a … video game. Yes, in 2002, the obscure title Shenmue II was released for the Microsoft Xbox. The game finds our character, Ryo, in Hong Kong after leaving Japan to follow the plot (which I won’t get into here). He travels from Aberdeen Harbor to the brownstones on Queen’s St. to middle class Wan Chai. He (or I) finally makes his way to Kowloon Walled City, complete with the decrepit towers previously mentioned. The game takes place in the mid 1980s, years before the eventual destruction of the buildings. The simulation city features gambling destinations, and is the headquarters of Lan Di’s (the villain) dangerous friends. This was close to reality, as the Triads organized crime syndicate made their stronghold there. They operated brothels and opium distribution centers, as well as the gambling scene.

And so this community grew organically, albeit as a substandard slum. Hak Nam echoed, in many ways, the 1960s rise of the Japanese Metabolists in academia, who proposed ‘plug-in’ megastructures whose living cells could constantly grow and adapt over time. The work of Kisho Noriaki Kurokawa is exactly that: the Nakagin capsule tower (1971) in Tokyo is very Futurist, a building with white blocks connected together, each with one circular window. It looks as if the capsules could be stacked onto one another forever. Kiyonori Kikutake’s ideas were even more extreme. His visions were more theoretical or poetic than Kurokowa’s; he proposed prefabricated pods clipped on to vast helicoidal skyscrapers.

Within that movement, however, voices of dissent began to rise. “As long as the actual buildings got heavier, harder and more monstrous in scale, as long as architecture is taken as a means to power, the talk of greater flexibility is just fuss,” Fumihiko Maki, Masato Otaka and Gunter Nitschke had said in 1966. Maki himself was a member of the Metabolist group himself, but distanced himself more and more, abandoning the ideas of an organically growing building in favor of cubistic collages. He eventually moved to a aesthetic of fragmentation, but was more of a technologist, favoring metal trusswork and stainless steel superstructure and sheets. There is a certain Japan-ness still, but it is closer to Richard Rogers structuralism meets Tadao Ando’s minimalism than anything having to do with Metabolism.

The essence of Metabolism was that built environments should not be static, but should be capable of undergoing constant change. Rather than thinking in terms of fixed form and function, these architects wanted to build system of parts that could continuously evolve. Maki was more interested in “group form,” and the urban spaces between buildings: “One makes static compositions of individual buildings, and only subsequently can they become aspects of the grain of the City. The vital image of group form, on the other hand, derives from the dynamic equilibrium of generative elements and not a composition of stylizes and finished objects.” Maki might be talking here about metabolism on an urban scale.

The original ideas of the Japanese Metabolists have been filtered down into a meaningless, contrived aesthetic. The April 2009 Architectural Record reports that the Dutch firm MVRDV is designing Rødovre, a stepped tower, or “stacked neighborhood” of “pixels” which are mixed and matched to form a Lego-like mass. Unlike the examples previously mentioned, megastructures generated as a collection of units, Rodovre is only looks like this on the outside. The Metabolist dream provides no more than theatrics at the ground level, terraces throughout the building (which are nice) and an interesting shape. And so, 20 years later, the original anarchy of Kowloon reaches its endpoint: the City of Darkness transformed into an empty high-end condo aesthetic.

Observed

View all

Observed

By James Wegener

Related Posts

Graphic Design

Sarah Gephart|Essays

A new alphabet for a shared lived experience

Arts + Culture

Nila Rezaei|Essays

“Dear mother, I made us a seat”: a Mother’s Day tribute to the women of Iran

The Observatory

Ellen McGirt|Books

Parable of the Redesigner

Arts + Culture

Jessica Helfand|Essays

Véronique Vienne : A Remembrance

Recent Posts

Beauty queenpin: ‘Deli Boys’ makeup head Nesrin Ismail on cosmetics as masks and mirrors Compassionate Design, Career Advice and Leaving 18F with Designer Ethan Marcotte Mine the $3.1T gap: Workplace gender equity is a growth imperative in an era of uncertainty A new alphabet for a shared lived experienceRelated Posts

Graphic Design

Sarah Gephart|Essays

A new alphabet for a shared lived experience

Arts + Culture

Nila Rezaei|Essays

“Dear mother, I made us a seat”: a Mother’s Day tribute to the women of Iran

The Observatory

Ellen McGirt|Books

Parable of the Redesigner

Arts + Culture

Jessica Helfand|Essays

James Wegener studied both Architecture and History at Washington University in St. Louis, earning a B.S.Arch in 2005. There he joined the Hewlett Program (building community in St. Louis architecture), participated in Architecture for Humanity, won the Fitzgibbon Design Competition and was a DJ for KWUR 90.3 FM.

James Wegener studied both Architecture and History at Washington University in St. Louis, earning a B.S.Arch in 2005. There he joined the Hewlett Program (building community in St. Louis architecture), participated in Architecture for Humanity, won the Fitzgibbon Design Competition and was a DJ for KWUR 90.3 FM.