June 30, 2020

Milton Glaser: Work = Love

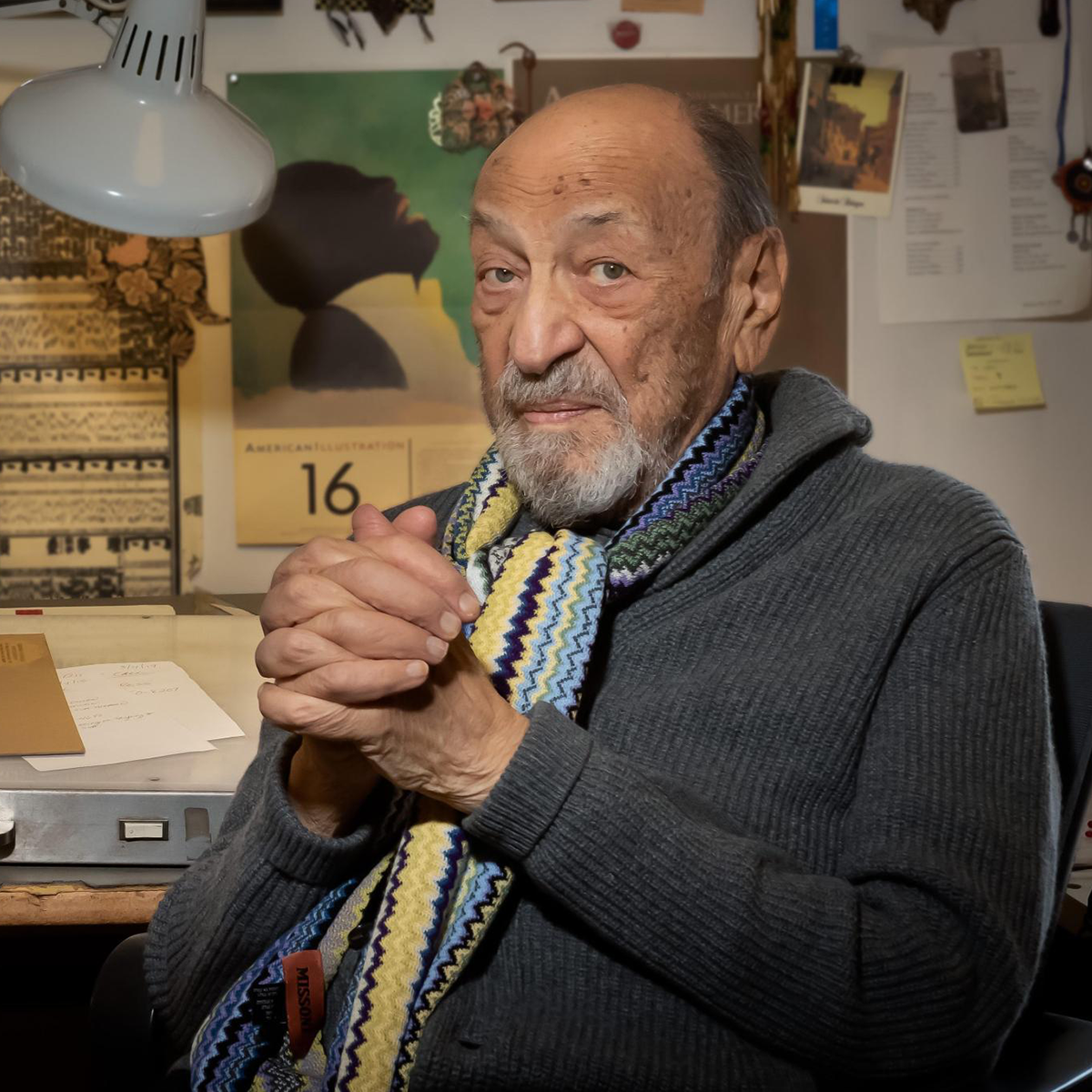

Milton Glaser photographed by Leo Sorel

EDITOR’S NOTE: The following is an essay by design writer Anne Quito, profiling Milton Glaser, who died last week on his ninety-first birthday. In honor of Glaser’s remarkable design legacy, we will be publishing a number of Quito’s essays. This is the second. You can read the first here.

Today (June 26) is Milton Glaser’s 90th birthday and he is spending it in his happy place: the office.

“I’m still working on a daily basis and nothing could please me more,” he beams. For the celebrated graphic designer, work is a source of vitality and well-being.

Born to Hungarian Jewish immigrants in the Bronx, New York, Glaser learned about the virtue of regular toil from his parents, who ran a dry cleaning and tailoring business in what was then the borough’s “Little Moscow” enclave. Glaser’s first job involved helping his father tend their small shop—fetching fabrics and threads, logging customers’ orders, and delivering laundry. He saved his wages for comic books such as Smokey Stover and Superman. It was from studiously copying those comic books that Glaser would develop an early aptitude for draftsmanship.

Almost without fail, Glaser reports to his Manhattan studio five days a week, albeit with a bit more caution these days about climbing the four-story walk-up on 32nd Street. He says he isn’t particularly looking forward to any grand birthday celebrations at the office today, partly because they would cut into time he can spend being productive. Spending 65 years in the business and garnering countless accolades, including the National Medal of the Arts from former US president Barack Obama, hasn’t inspired him to think of withdrawing from professional life.

“The idea of retirement is disgusting to me,” he says. “I would drive my wife nuts for one thing.”

Retirement, Glaser argues, is an outdated construct from the industrial age. “For many people, work was unpleasant labor. If you work in a factory and all you did was move widgets, you’d eventually get tired. Retirement fit in with the nature of industrial work, but that’s not true of artists and painters.” He cites Claude Monet and Pablo Picasso—artists he admires—as examples of this.

“It’s a question of purpose,” says Glaser. “For me, a big part of that is teaching which has enriched my life in so many ways,” he explains, referring to a 62-year tenure teaching graphic design at the School of Visual Arts.

A prolific illustrator and designer for books and magazines, Glaser says the decline of his motor skills has altered the way he works. “I can still can draw to some extent, but the ambitious kind of drawing, I don’t have the patience for,” he says. “On the other hand, my mind seems to have become more exploratory.”

A self-described Luddite, Glaser works closely with illustrator Ignacio Serrano these days.”We have found another way of working. We’re doing interesting work, aided in this case with this mechanical contrivance,” he says, referring to the computer. He is particularly enamored with a texture effect achieved by layering hand-drawn patterns over his illustrations in Photoshop. “At the moment I feel very capable of doing the work,” he says.

Milton Glaser in his studio photographed by Leo Sorel

There is no shortage of projects in Glaser’s inbox. He is currently working on a series of portraits for a forthcoming exhibition about William Shakespeare and experimenting with new channels for selling his posters and fine art prints. He still fields requests for logos, posters, and illustrations from various clients around the world.

I witnessed the kinetic qualities of Glaser’s mind up close, while working with him and his former design partner Walter Bernard on their forthcoming book. Days after wrapping up the book, Glaser started, and completed, prototypes for two children’s books and is now collecting material for his next major monograph.

“Not having anything to do sounds terrible,” Glaser says. “I fear that more than anything else. It’s greater than the fear of death.”

There have been times when Glaser has juggled multiple major assignments. After returning from Rome on a Fulbright scholarship in 1954, he and Cooper Union classmate Seymour Chwast ran Push Pin Studios, then among the most sought-after design studios in the US. On top of that, he co-founded New York magazine with Clay Felker in 1968.

Apart from being the magazine’s design director, he wrote The Underground Gourmet column with Jerome Snyder and established a reputation for being the city’s preeminent cheap-eats food critic. Around that time, Glaser also had a cookbook imprint with James Beard and was a design consultant to the city’s top restauranteur, Joe Baum. He designed the interiors and identity for prestigious establishments such as Windows on the World, Aurora, and the Rainbow Room. In the midst of a top-to-bottom overhaul of the Grand Union Supermarket chain, Glaser formed a publication design consultancy with Bernard in 1983—all this in addition to running his own separate design practice, teaching classes and giving lectures around the world.

A significant portion of Glaser’s time lately has been devoted to downsizing his studio in preparation for a move to a smaller office at the School of Visual Arts’s Chelsea campus, which, among other advantages, has an elevator. Evidence of his long and varied career—sketches, paste-up boards, architectural maquettes, product samples, client correspondence, I ♥ NY swag (he designed the iconic logo in the 1970s)—occupy much of the studio’s floorspace.

Glaser confesses that he’s anxious to shed the work that he’s been known for and create anew. “Anybody with a lively mind doesn’t want to stop using their brain,” he says. What better way to mark 90 years than to put a restless brain to work?

This article was originally published in 2019 in Quartz. It is reprinted with permission of the author and the publisher.

Observed

View all

Observed

By Anne Quito

Related Posts

Equity Observer

L’Oreal Thompson Payton|Essays

‘Misogynoir is a distraction’: Moya Bailey on why Kamala Harris (or any U.S. president) is not going to save us

Equity Observer

Ellen McGirt|Essays

I’m looking for a dad in finance

She the People

Aimee Allison|Audio

She the People with Aimee Allison, a new podcast from Design Observer

Equity Observer

Kevin Bethune|Essays

Oh My, AI

Recent Posts

Make a Plan to Vote ft. Genny Castillo, Danielle Atkinson of Mothering Justice Black balled and white walled: Interiority in Coralie Fargeat’s “The Substance”L’Oreal Thompson Payton|Essays

‘Misogynoir is a distraction’: Moya Bailey on why Kamala Harris (or any U.S. president) is not going to save us New kids on the bloc?Related Posts

Equity Observer

L’Oreal Thompson Payton|Essays

‘Misogynoir is a distraction’: Moya Bailey on why Kamala Harris (or any U.S. president) is not going to save us

Equity Observer

Ellen McGirt|Essays

I’m looking for a dad in finance

She the People

Aimee Allison|Audio

She the People with Aimee Allison, a new podcast from Design Observer

Equity Observer

Kevin Bethune|Essays