September 7, 2017

Narration vs. Curation: Deyan Sudjic, the Design Museum, and B Is for Bauhaus

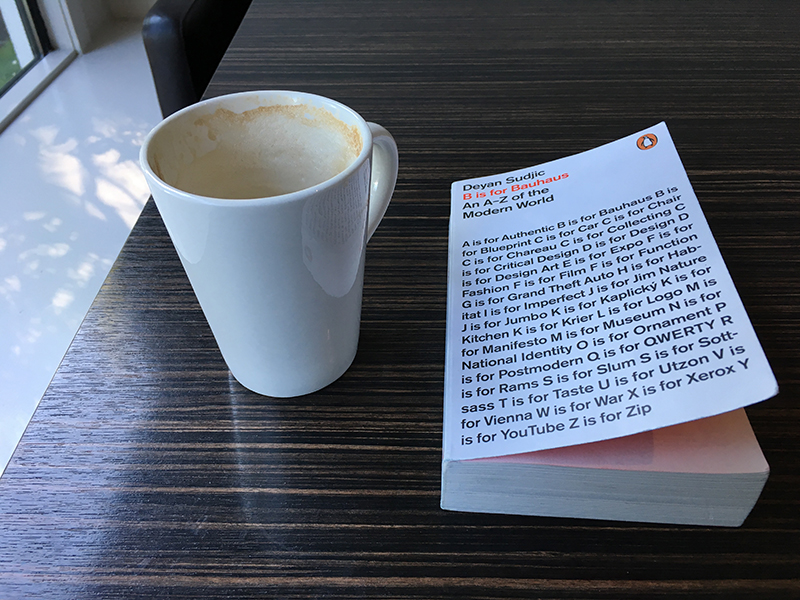

A few weeks ago, I found myself wandering around the gift shop of London’s Design Museum. I had enjoyed the museum, which cost nothing to enter, but felt exhausted. There were too many interesting objects to inspect. Too many explanatory videos to watch. Too many people jammed into one place. It was like spending the day at a mall. I yearned for a more quiet, private, text-based experience. A book. I noticed a squat white volume featuring a small penguin encircled in orange—the iconic sign of literary quality—called B Is for Bauhaus, by Deyan Sudjic. I rejoiced. I had devoured Sudjic’s The Language of Things: Understanding the World of Desirable Objects, right before starting my current job at Continuum, the global innovation design firm. B was a find!

Eying the first paragraphs, I started to think about literature as an introvert’s ideal version of a museum visit. To read a book is to stage an exhibition in one’s own imagination. You build and furnish the rooms. Put people in them. The pacing is yours. You can leave whenever you want, or return again and again to different exhibits, without having to encounter any other visitors or security guards or anything.

Moments after purchasing the volume, a bit of Sudjic trivia flew to mind: I recalled, from his bio in The Language of Things, that he was the Director of the Design Museum! I jogged to the museum’s reception desk to learn if Sudjic was in the building, but it wasn’t the right day. I didn’t get to meet the director and author. Instead, though, I had something much better: his best words most carefully preserved between two covers.

***

At Continuum, we spend much time thinking about the relationship between product design and experience design. We don’t just consider creating an object that a person might buy or use, but we also imagine the experience that surrounds it. We wonder about services that might support people who use it, and about the ecosystem where it is, or could be, planted. There are, as you might imagine, many business and ethical implications in thinking this way.

Well, my designer colleagues are the ones who do this work. My job is to write about it, and to help others do so. But my readings of Sudjic made me wonder: Is there a way that “content,” as it’s called in the vernacular, can be both a product and an experience? Turns out, the answer is yes.

B Is for Bauhaus is a product. Visiting the Design Museum, on the other hand, is an experience. In B, Sudjic thinks at length about how he’s transitioned from design journalist into a museum director, and was been lost and gained in the process.

“One of the most striking differences I found in making the transition from editing architecture and design magazines to directing a museum was discovering that impact of seeing the audience face to face,” he writes. “To edit a magazine is to find yourself putting messages in bottles and floating them out to sea.” Maybe there is the occasional angry letter or threat of litigation, but no more than that.

This passage betrays the fact, of course, that Sudjic was an editor—at Blueprint and Domus—years ago, long before social media tore down the scrim between publications and public. In this video interview with online editor Marcus Frairs, Sudjic learns how the online magazine Dezeen has an infinitely closer relationship with readers. But no matter: the larger point still holds. The museum is a qualitatively different experience from the book and the print mag. And, as we know, people today are more interested in experiences than in things.

“Running a museum is more like running a theatre,” writes Sudjic. I recall seeing Andrew Scott play Hamlet while in London, and it was an experience of Shakespeare that simply can’t compare to any solitary reading I’ve ever done. As many times as I’ve read Hamlet, I never quite felt it as deeply as when I heard, from my limited-visibility seats toward the back of the Harold Pinter Theatre, Scott and his colleagues perform the play.

Sudjic says that with a museum, “There is a visible response to the programme. If people like what the museum is doing they come and spend time there. You can see when they enjoy what they find. You hear them talking to each other about it. You see them taking photographs of the captions on their mobile phones. Of course, if they don’t like it, you can see that too. They don’t come.”

Visibility is important because it leads to the matter of audiences, numbers, and business models. Editing a magazine and running a museum are two different ways to bring the story of design to the public—but there are some salient economic differences. When it comes to comparing design writing and running a museum, writes Sudjic, “The numbers are very different. Architectural exhibitions can very occasionally attract a hundred thousand paying customers or more. No issue of any architecture of design magazine in the world sells anything like that number. This is not to make any qualitative judgments about the value of one medium against another. But it is clear that there is something about an exhibition that, when it works, will persuade many more people to pay for the experience than would invest the same amount in a book or a magazine.”

In some ways, the move from producing a thought-leadership product, such as a book or magazine, to a thought-leadership experience, such as a museum, is about hedging one’s bets. If the point of your work is to bring the story of design to a larger group, and to generate revenue, then you might well pour your energy into curation rather than narration. But it’s important to note those words “can very occasionally attract a hundred thousand paying customers.” This means that most of the time, exhibits fail to achieve monstrous success. It seems something like venture capital, which, according to this study, has a 70% failure rate.

“An engaging physical exhibition on architecture does indeed offer a richer, more immersive experience that speaks to more people than any description in a book or magazine,” writes Sudjic.

I don’t entirely buy the “more immersive experience” argument. And here’s why: my experience as a reader informs me that when I enter into a text, I leave this world. It’s a way of trying on the consciousness of an author, or perhaps a character. A museum visit, while rich in various stimuli, is for most people, a one-time event. Unlike most museum visits, reading is, for the serious reader, anything but a one-visit deal. As the great Vladimir Nabokov said, “…one cannot read a book: one can only reread it. A good reader, a major reader, an active and creative reader is a rereader.” Reading is a long-term immersion; exhibits are here today, gone tomorrow.

***

One of the things that’s so fascinating about B Is for Bauhaus is that his design discourse has no illustrations. You have to make yourself envision Sudjic’s world; you have to work hard, in collaboration with the author, to see what’s going on. In some ways, this puts the unillustrated author, as opposed to the curator, in a difficult position. By demanding more of the participant than a museum curator does, the writer creates “pain points,” for many would-be readers. But there is a way to reach them, and Sudjic writes about it.

In B Is for Bauhaus, Sudjic talks about Turkish writer Orhan Pamuk and his novel The Museum of Innocence, in which the protagonist builds a museum of personal memories. Off the page, Pamuk followed suit, with a real-life museum of innocence. “Pamuk didn’t just explore the meaning of collecting in fictional terms in his novel, he built an actual collection, and a museum to accommodate it, in Beyoglu, the area of Istanbul in which its Jewish, Greek, and Armenian citizens lived until the collapse of the Ottoman empire.”

There is, in this experiment, Pamuk’s attempt to bridge literature as a product and experience. Creating a museum for a book is interesting way to try and close the gap between showing and telling.

Of course, the Nobel Prize-winning Pamuk has far more resources than most other novelists. But maybe publishing houses might think about creating some curated spaces of their own. Perhaps publishing houses and museums, or galleries, could work together on this. I know someone who spent an absurd amount of money to take his kids on a thrilling visit to Harry Potter Studios. There’s much to be learned from that particular experience…

***

So where does this leave us? Obviously, both written narratives and museum exhibitions have a place in design’s future. It may be that journalists, and magazines, are currently at a disadvantage as print becomes less and less viable—and bucket-list art becomes a thing. But we’d be wrong to think that text is now a thing of the past. For the rare reader who wants it, it’s a terribly engaging activity, one that is far less passive than mere experience design (and much cheaper to produce). At the end of the day, a general admission ticket to the Design Museum didn’t cost me a red cent—though I could have paid £12 each to see the museum’s California: Designing Freedom or Breathing Colour by Hella Jongerius—but I happily ponied up £12 for B Is for Bauhaus. (Interesting that the exhibits and Sudjic’s book have the same price point, no?) I don’t know if I’ll go back to the museum again—but I’ll surely reread that book. You tell me which is more valuable.

Observed

View all

Observed

By Ken Gordon

Related Posts

Business

Courtney L. McCluney, PhD|Essays

Rest as reparations: reimagining how we invest in Black women entrepreneurs

Design Impact

Seher Anand|Essays

Food branding without borders: chai, culture, and the politics of packaging

Graphic Design

Sarah Gephart|Essays

A new alphabet for a shared lived experience

Arts + Culture

Nila Rezaei|Essays

“Dear mother, I made us a seat”: a Mother’s Day tribute to the women of Iran

Recent Posts

Candace Parker & Michael C. Bush on Purpose, Leadership and Meeting the MomentCourtney L. McCluney, PhD|Essays

Rest as reparations: reimagining how we invest in Black women entrepreneurs Food branding without borders: chai, culture, and the politics of packaging Why scaling back on equity is more than risky — it’s economically irresponsibleRelated Posts

Business

Courtney L. McCluney, PhD|Essays

Rest as reparations: reimagining how we invest in Black women entrepreneurs

Design Impact

Seher Anand|Essays

Food branding without borders: chai, culture, and the politics of packaging

Graphic Design

Sarah Gephart|Essays

A new alphabet for a shared lived experience

Arts + Culture

Nila Rezaei|Essays