Jessica Helfand|The Self-Reliance Project

December 3, 2020

On Learning

What follows is the preface to a collection of essays on self-reliance—originally posted here on Design Observer—to be published early next year by Thames & Hudson, in conjunction with the original 1841 Ralph Waldo Emerson essay that inspired them. (Pre-order your copy here.)

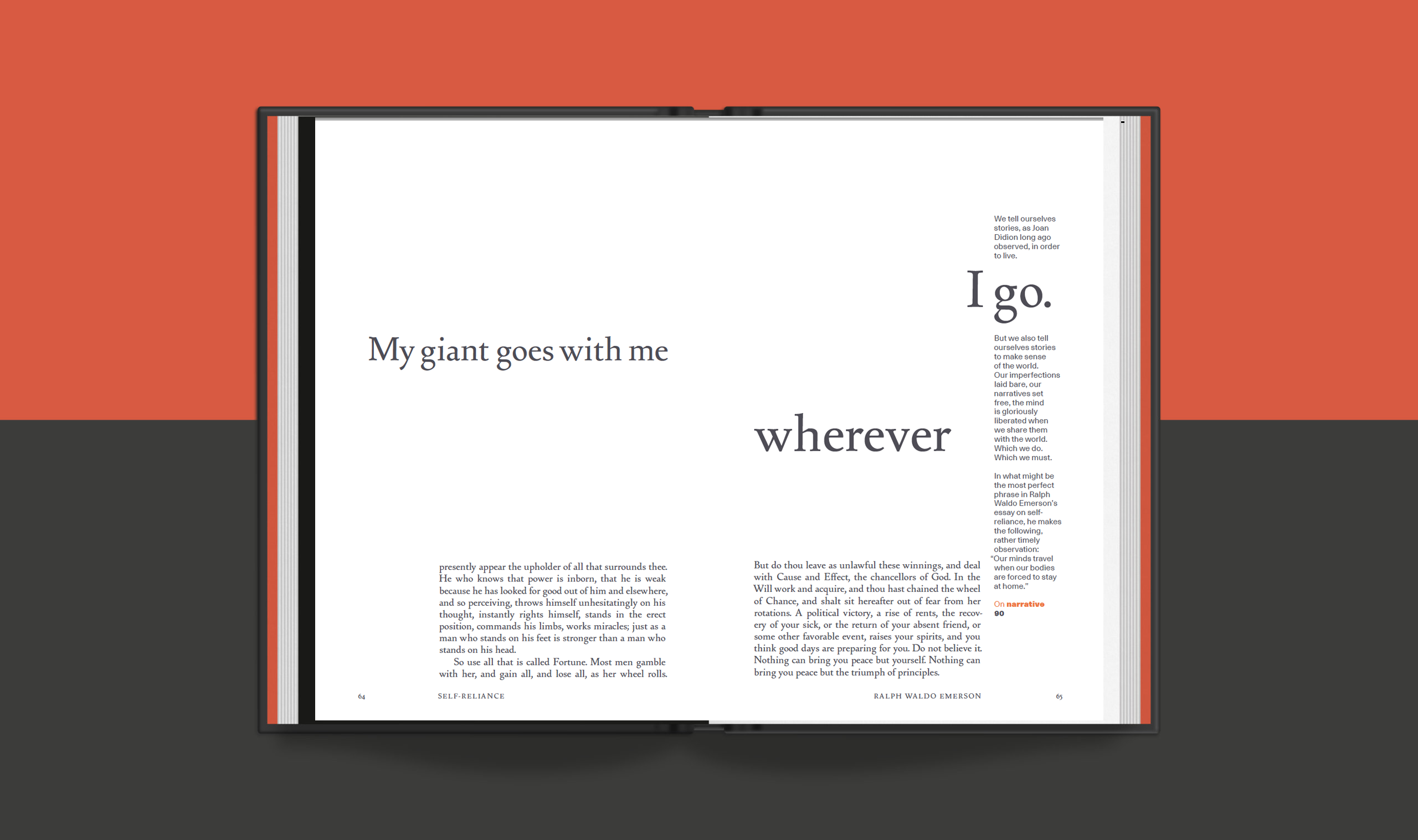

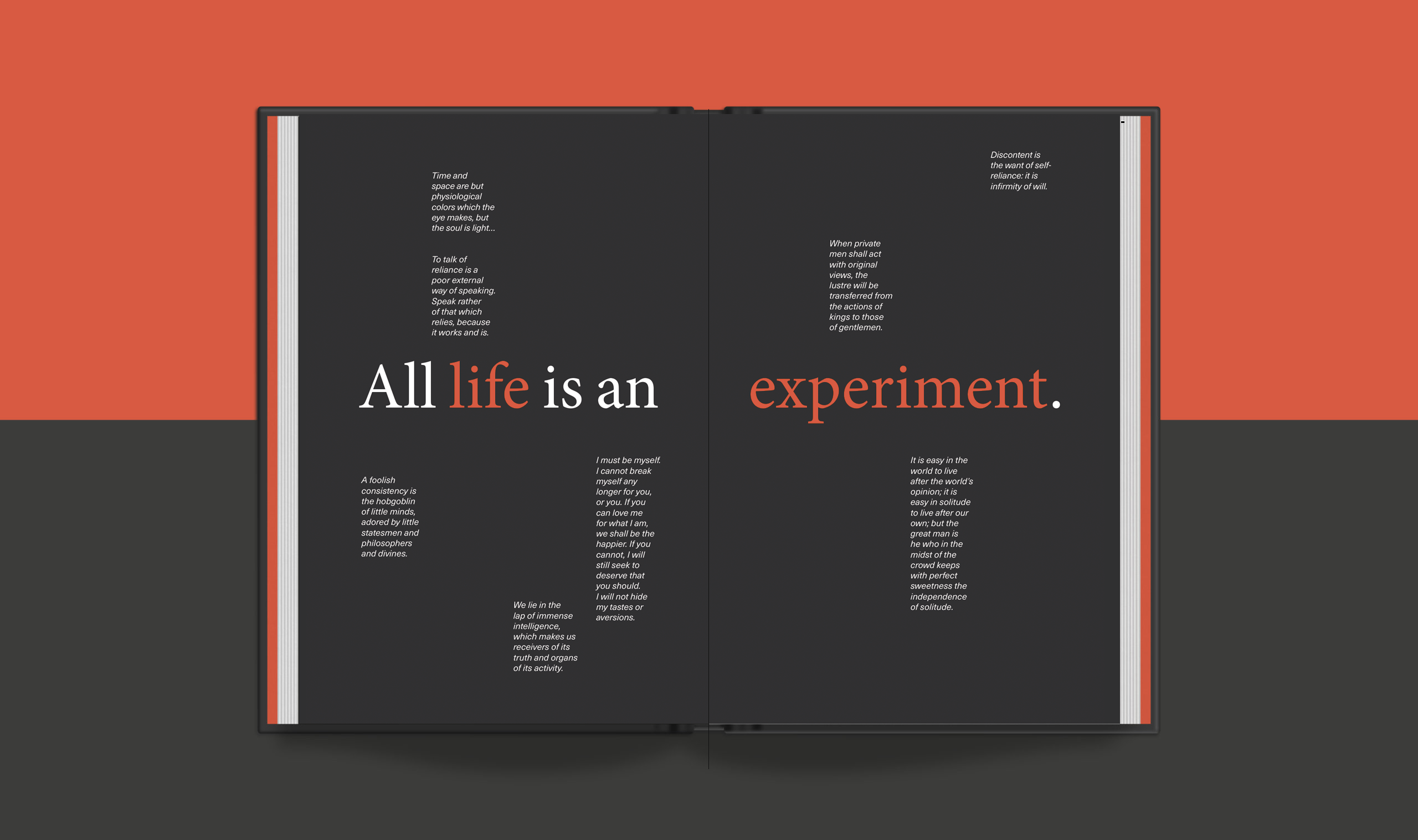

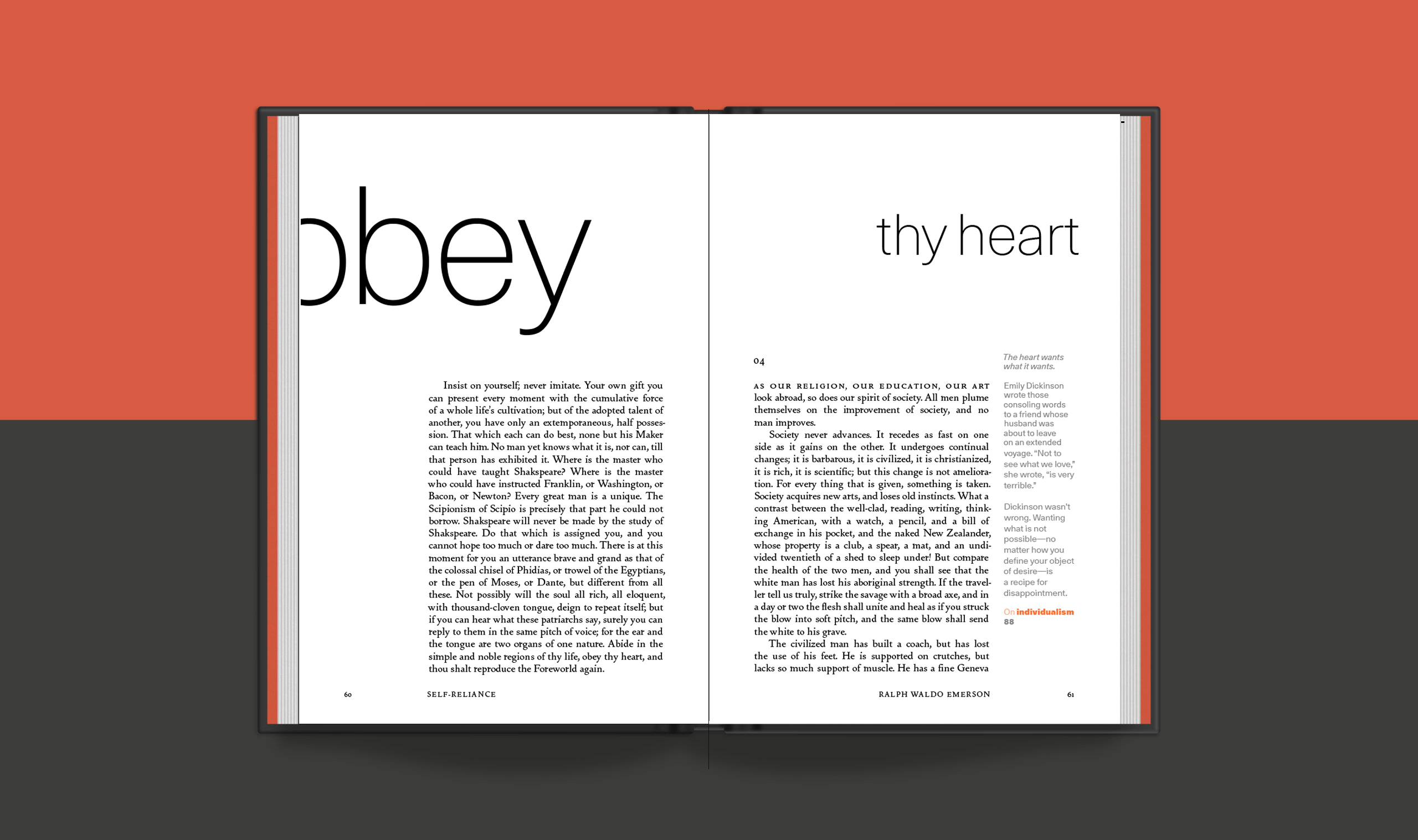

Spread from Self-Reliance (forthcoming, Thames & Hudson, 2021.) Book Design : Jessica Helfand + Jarrett Fuller.

I learned how to be alone the hard way.

My mother died when I was still young and my own children were small. Within a decade, I would also lose my husband. Personal loss, always irrevocable, became an all-out war, an assault on the psyche, and a blow (many blows, actually) to the heart.

I was suffering, but I was impatient. I’d been abandoned, and I felt ashamed. I felt sorry for myself, angry at the world, and envious of everyone else who, I was certain, had it way better than I did. Weekends were onerous. Social media was hell. I was mournful of the past, worried for the future, and seemingly incapable of processing any of it.

But when, just a few years after the loss of my children’s father, my own father died, everything stopped. I couldn’t work or sleep or eat. I cried at the slightest provocation. I canceled my classes, withdrew from everything, and hid from everyone. This newly minted round of loss led to an unprecedented sense of personal dislocation: without warning, it seemed, I’d lost myself. Which required that I find myself. And which I did, quite simply, by returning to the studio.

In the spring of 2020, as the first waves of the COVID-19 virus surged, I was finishing up an artist’s residency in Los Angeles when California issued the nation’s first stay-at-home order. Other states would follow, then other countries would follow, and suddenly the world had stopped once again.

This time, I was ready.

Locked down and on my own some three thousand miles from home, I walked the periphery of my studio, in choreographically limited loops, logging upwards of six miles daily. By day, technology offered the illusion of staying connected (to what, I’m not certain), while at night I painted portraits of the people appearing on my TV screen, the only people I was seeing on a regular basis. As the days wore on, I found myself thinking increasingly about isolation and loneliness, about what it meant to secede from structure, to pierce the forcefield of routine. I thought about leaderless teams and rudderless weeks, and about the systems upon which all of us, for so many reasons (and for so long), have come to rely. Some of those systems are conversational: we rely on being in dialogue with others. Some are congregational: we rely on being in the company of others. And some are computational: we rely on a non-human (but non-stop) infrastructure of coordinated technologies that serve as our tireless, if remote, proxies. When quarantine went global, that alt-circuitry kicked into overdrive, social distancing a catalyst to sentient dislocation.

All of which begged the question: when so much of what you’ve been groomed to rely upon vanishes from view, where do you go?

Enter Emerson.

“To talk of reliance is a poor external way of speaking,” he wrote. “Speak rather of that which relies, because it works and is.”

This is the essence of Emerson’s seminal essay on self-reliance, originally published in 1841 and reproduced here in its entirety (which is to say, unedited). A cursory glance may grate on the sensitive reader. This is, after all, the writing of a supremely confident man, whose language reflects the privilege and purview of a different era. American, Caucasian, schooled in the liturgical (and with a flair for the theatrical), Emerson made his living as a lecturer, and his authoritative tone can read as discomfiting, even didactic.

But a closer read reveals something far more meaningful and relevant. This is a meditation on what it means to be human, to have an imagination, and to use it.

Emerson’s writing lacks pretense, yet abounds in spirit. His intellectual reach is capacious, but his emotional truth is unwavering. There is piety and there is poetry, but what resonates most unequivocally here is his plea for individuality—that “iron string”—the sovereignty of selfhood. To read Emerson today is to rethink the flawed calculus that’s led you to equate value with consensus, and to imagine instead what it might mean to hear your own voice, to heed your own motives, to hold fast to your own capacity for reason, reflection, and wonder.

Wonder is key. Emerson was, as the late American literary critic Harold Bloom once observed, the dominant sage of the American imagination. Prolific and charismatic, he inspired writers from Emily Dickinson to Walt Whitman, Henry James to Hart Crane. Robert Frost adored him. Robert Penn Warren did not—he called him the devil—and it bears saying that not all of Emerson’s ideas were worthy. (He believed, for instance, that Texas should secede from the Union.) He could be kooky, often endearingly so, and had his share of conspiracy theories. Ever the non-conformist, he viewed history as an impertinence. This is a man who, after all, once referred to himself as a transparent eyeball. Were he to be alive today, noted Bloom, he’d be a performance artist.

Artists, of course, are all too familiar with addressing the sorts of questions best answered by process itself (we sometimes call this thinking through making). But what are the questions, and what is the process? How do you start, and where do you end? The shifting coordinates of a global pandemic unsettle even the most seasoned and skilled among us—and how could they not? Here, Emerson’s call to independence is not so much an edict as an invitation: less a reckoning than a beckoning. In the spirit of that invitation, the twelve accompanying essays in this volume address various aspects of creative engagement—writing, drawing, thinking, making—not intended as reinterpretations of a canonical essay, but as reactions to it. Framed as a way to rethink creative practice, they consider, both individually and collectively, how to push that practice forward, and let it push you right back.

In the end, self-reliance pushes back, too: our individual survival requires nothing less. Good days meet bad days, aspiration derailed by the pain of unbidden circumstance. Emerson, for his part, was no stranger to sorrow. He lost his first wife to tuberculosis at the age of twenty, and his first child to scarlet fever at the age of five—a scant year after writing this essay. Did his faith waver, ineffable goodness overtaken by unspeakable grief? Perhaps the honesty protected him. (Perhaps the writing rescued him.) Or perhaps Emerson simply understood what so many of us do not: that life is one infinite loop, one ever-present Möbius strip of hope mixed with hurt. Long before a global pandemic would oblige us to steer clear of one another, more than a century before lockdowns interfered with our best laid plans, Emerson knew better.

“The days pass over me,” he wrote. “And I am still the same.”

Self-reliance is where it all begins, and ends, and begins once again. Maybe this is the real infinite loop: that hard-won human circuitry that sustains us through so much ambiguity, uncertainty, and loss.

“Nothing is at last sacred,” Emerson noted, “but the integrity of your own mind.” Learning to be alone, it turns out, is the easy part.

Observed

View all

Observed

By Jessica Helfand

Recent Posts

Compassionate Design, Career Advice and Leaving 18F with Designer Ethan Marcotte Mine the $3.1T gap: Workplace gender equity is a growth imperative in an era of uncertainty A new alphabet for a shared lived experience Love Letter to a Garden and 20 years of Design Matters with Debbie Millman

Jessica Helfand, a founding editor of Design Observer, is an award-winning graphic designer and writer and a former contributing editor and columnist for Print, Communications Arts and Eye magazines. A member of the Alliance Graphique Internationale and a recent laureate of the Art Director’s Hall of Fame, Helfand received her B.A. and her M.F.A. from Yale University where she has taught since 1994.

Jessica Helfand, a founding editor of Design Observer, is an award-winning graphic designer and writer and a former contributing editor and columnist for Print, Communications Arts and Eye magazines. A member of the Alliance Graphique Internationale and a recent laureate of the Art Director’s Hall of Fame, Helfand received her B.A. and her M.F.A. from Yale University where she has taught since 1994.