December 3, 2010

On My Screen: Bill Morrison’s Decasia

DVD cover, Plexifilm, 2004

I had never heard of Decasia when I chanced upon a copy of the DVD a few years ago among some carefully curated items for sale at the Museum of Jurassic Technology in Culver City, Los Angeles. The title seemed to promise a fantasia of decay and the subtitle, “The State of Decay,” left no room for doubt. When I read the line on the back – “an experimental feature which sets decayed archive film footage to an original symphonic score” – I knew this was going to be something special. And it was.

What is it about the idea of decay? The prospect of an object or entity falling into a state of dissolution and decay should be alarming and repellent. Something is whole, unblemished, harmonious, functional and perfect. We want it to last forever. We wish it could resist the erosion of time, but we know its perfection is only temporary and that all things, man-made and organic, will come to an end. Matter coalesces into form and then it dissolves, in an endless cycle of creation and collapse. From this realization arises the fascination with decay. When you observe the process of something wearing out and beginning to fall apart, you confront the truth of how things are. Consoling and perversely exciting, the spectacle of decay helps us to face the certainty that this will also happen to us.

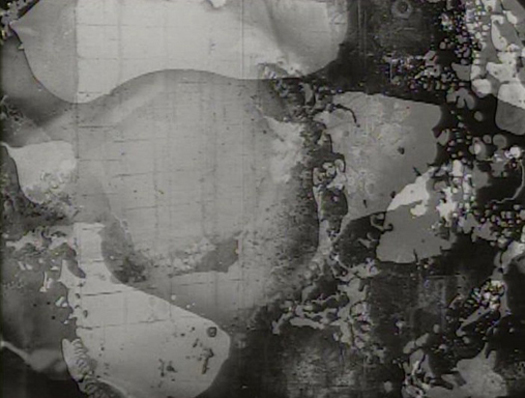

Decasia shows the effects of decomposition on unstable nitrate-based stock sourced from film archives. The director, Bill Morrison, estimates that he sifted through close to 1,000 films shot between 1914 and 1954. Some of the black-and-white footage is so corroded that the image has been entirely obliterated, leaving only bubbles, splatters and splotches that resemble a 1960s psychedelic lightshow. Most of the found sequences show people and these decaying images rank as some of the most astonishing seen on film. A boxer slugs it out stoically with an ectoplasmic blob; an angry woman’s head melts into swirling vapor trails; the rocket cars of a fairground ride burst free from a writhing envelope of chaos.

DVD cover, British Film Institute, 2004

The first time I watched Decasia, excited to find that it was even better than I’d hoped, I only partly sensed its hidden structure. The 65-minute film begins and ends with a whirling dervish dancer, who also reappears part way through. Other images recur, notably a Japanese woman. But uncertainty about where this strange experience is heading, if anywhere, combined with the intense passing beauty of the images, hinders sustained attempts to uncover a narrative. Then there is Michael Gordon’s equally overwhelming score, a barrage of dissonant minimalism, which is like a huge percussive juggernaut with its breaks on, sliding along the rails with horns and sirens blaring. It takes repeated viewings to perceive the pattern in the chaos.

In interview, Morrison has been surprisingly candid about the framework that underpins Decasia’s fissured and seething surface — artists often prefer not to give viewers the keys to a definitive explanation. The entire film, he says, is the meditation of the Sufi dancer at the beginning, and the film laboratory that appears next, with its perpetually turning reels of celluloid, is a kind of heaven where the Gods ponder our lives. One of these films is the dream of a Japanese goddess. Decasia unfolds in four movements — Creation, Civilization, Conundrum, Disintegration and Rebirth — and at the end the Japanese goddess awakes from her dream.

Decasia isn’t, however, divided into clearly indicated sections and Morrison’s explanation goes into more detail than most viewers are likely to deduce without aid. Symbolic readings always seem overly reductive to me, foreclosing other interpretations, so I prefer not to apply his exegesis too literally. Nevertheless, Decasia’s general meaning is clear. These people are probably all dead now and even the celluloid carrying their fragile likenesses was perishing until Morrison rescued these fragments. The only adjustment he made to the footage was to repeat each frame two or three times, slowing the sequences down, which gives them an air of monumentality even as the rogue chemical reactions consume them. It also allows viewers a little longer to study images that are, in effect, tantalizingly exquisite and evanescent paintings in light.

Resurrected in Decasia, these time travelers battle against entropy, gaze out at us solemnly, or simply wave their hats or hands. In one of the film’s faultlessly crafted counterpoints, the microscopic life seen at the start finds a return in the parachutes falling to earth at the end — a long sequence of mesmerizing power. For me, this inexhaustible film is neither a dream nor the apocalyptic nightmare some have seen in it. It’s a cracked and tarnished mirror reflecting the cycle of life and death to offer sublime glimpses of another reality.

Plexifilm, the company started by Gary Hustwit, who later directed Helvetica and Objectified, released Decasia on DVD in the U.S. in 2004. The rights have since reverted to Morrison. The British Film Institute, whose DVD of Decasia is also out of print, will reissue the film, along with shorter films by Morrison, in 2011.

Observed

View all

Observed

By Rick Poynor

Related Posts

Business

Courtney L. McCluney, PhD|Essays

Rest as reparations: reimagining how we invest in Black women entrepreneurs

Design Impact

Seher Anand|Essays

Food branding without borders: chai, culture, and the politics of packaging

Graphic Design

Sarah Gephart|Essays

A new alphabet for a shared lived experience

Arts + Culture

Nila Rezaei|Essays

“Dear mother, I made us a seat”: a Mother’s Day tribute to the women of Iran

Recent Posts

Courtney L. McCluney, PhD|Essays

Rest as reparations: reimagining how we invest in Black women entrepreneurs Food branding without borders: chai, culture, and the politics of packaging Why scaling back on equity is more than risky — it’s economically irresponsible Beauty queenpin: ‘Deli Boys’ makeup head Nesrin Ismail on cosmetics as masks and mirrorsRelated Posts

Business

Courtney L. McCluney, PhD|Essays

Rest as reparations: reimagining how we invest in Black women entrepreneurs

Design Impact

Seher Anand|Essays

Food branding without borders: chai, culture, and the politics of packaging

Graphic Design

Sarah Gephart|Essays

A new alphabet for a shared lived experience

Arts + Culture

Nila Rezaei|Essays

Rick Poynor is a writer, critic, lecturer and curator, specialising in design, media, photography and visual culture. He founded Eye, co-founded Design Observer, and contributes columns to Eye and Print. His latest book is Uncanny: Surrealism and Graphic Design.

Rick Poynor is a writer, critic, lecturer and curator, specialising in design, media, photography and visual culture. He founded Eye, co-founded Design Observer, and contributes columns to Eye and Print. His latest book is Uncanny: Surrealism and Graphic Design.