February 8, 2012

Pop Photographica: An Interview with Daile Kaplan

Photography as a whole is somewhat brilliantly encapsulated in photographic hybrid forms, a jubilant and disparate mix of every conceivable combination of elements: high and low art, finery and kitsch, private memories and public displays, truth and illusion, status symbols and humble means, artistic aspirations and commerce, the hand-made versus the mechanical, with photography playing a central role in all.

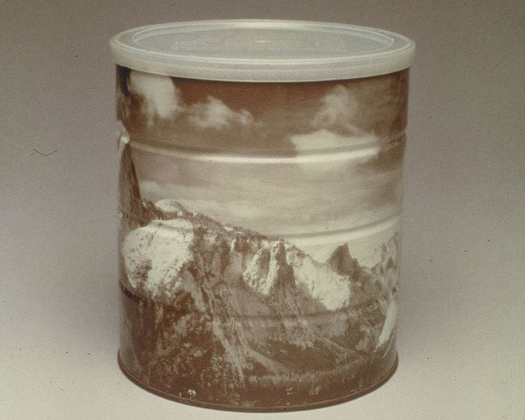

This series of seemingly endless contradictions is brilliantly expressed in Daile Kaplan’s comprehensive collection that includes the 1969 mass produced Ansel Adams coffee can pictured above. As it happens, Kaplan turns out to be a photographic expert at Swann Auction Gallery in New York City and guest appears as a Photographs Specialist on PBS’s The Antiques Roadshow but her own personal collecting interest in photography is — both literally and figuratively — off the wall. Her photographic collection encompasses early historic examples, such as Daguerreian mourning jewelry, 19th Century cyanotype quilts and folk art assemblages that feature real photographs as integral components. Her collection is firmly grounded in the 20th century, and favors such quirky, off-beat examples as a photomechanical printed lampshade of a deer perched upon a taxidermy lamp base, a picture-based Minstrel’s trunk and a series of photographic paper weights. What these objects share in common is a simple unifying trait: a photographic element that was not intended for viewing on the wall. As her collection evolved, Kaplan discovered that what she was surrounding herself with was indeed an overlooked photographic genre. In 1988, Kaplan named the genre “Pop Photographica”.

Michelle Hauser:

What have been your guiding principals for building this collection, and how do you define Pop Photographica?

Daile Kaplan:

In the very beginning, my collection didn’t benefit from a guiding principle. When I look back at the trajectory of my collection, that first “aha” moment was Cindy Sherman’s Limoges dinner service, in which she appears as Madame de Pompadour, this would be 1990. But, in fact, there were a few events that apparently occurred about the same time. A year or so before, Madeleine Burnside invited me to curate an exhibition celebrating the 150th anniversary of photography at the Islip Art Museum. In the mid-1980s I had been fortunate to spend time with Sam Wagstaff — an American aristocrat with populist photographic leanings and Alan Trachtenberg, professor of American Studies at Yale and a Hine scholar, who keenly understood how vernacular impulses influenced photographic practice. Their approaches to looking and talking about photography were brilliant, thrilling and inspirational.

My background probably reflects my collecting pattern. Like the photo objects, I’m something of a hybrid. At university, I studied New American Cinema (non-narrative filmmaking) and made films. But, I was also exploring photography independently as a mode of creative expression. After college, I entered the art world and had had a fun stint as a drummer in Rhys Chatham’s band, The Gynecologists and Martha Wilson‘s performance group, Disband. In the early 1980s, my life changed. From 1980-82 I was the photography consultant for the United Methodist Church, directing a preservation and research program for the 250,000 fine art and documentary photographs in their archive of secular and religious, national and international pictures, ranging from the 1890s-1940s. It was during this period that I discovered Lewis Hine’s “lost” European photographs, which were part of the Methodist archive (now at Drew University). Subsequently, I fell in love with historical imagery, and transitioned from being an artist to working as a curator, scholar and very briefly, an adjunct professor at N.Y.U.

As a young woman, I prided my self on having almost no possessions. During the many years I worked with Hine’s materials, it never occurred to me to purchase one of his photographs. Although I’m sure this sounds very odd, I was not prepared to be identified as a collector. The notion of actively acquiring objects was initially foreign until I found I enjoyed the art of discovery. There was, however, one inherent difficulty: the material that attracted me had no name, no context and no place in photographic discourse. Yet, I muddled on, aware that I was operating in a territory loosely referred to as vernacular photography.

MH: At what point did you begin to realize that the material you were collecting was an overlooked genre?

DK: As I built a small collection, I met individuals like Fred Spira, whose collection of viewing devices, detective cameras and unusual objects opened my world to other ways of looking at photography, as well as photographer-cum-vernacular collector Rodger Kingston, who compiled a remarkable collection of “forgotten masterpieces.” Soon after, my then editor at the Smithsonian Institution Press, Amy Pastan, suggested that I read texts relating to material culture, which keyed into photographic artifacts. After a few years of research, a unifying principle emerged. Coining the term “Pop Photographica” came about after spending time considering how these objects —some of which were unique, others mass produced — might be contextualized. The term is meant to address the convergence of photography and popular culture. It also embraces how “photographica,” once a word of diminishment associated with materials situated at the margins of fine art photography, might actually be useful. All of this came about slowly. Once I saw that this genre could be regarded as a new, hybrid category, in which multifarious articles by Victorian and modernist artists, artisans, homemakers, amateur photographers and contemporary artists, I began to feel more confident about the direction in which I was headed.

MH: What initially got you started? Was there a first piece that began this collection?

DK: The first article I purchased was a hat veil display in an antique shop in Jim Thorpe, PA. My partner and I are inveterate “antiquers” who spent a lot of time traveling and exploring shops throughout the country. The freestanding, circular cardboard item, which features a stunning picture of a woman’s face, was set in the shop’s front window. I did a double take, but then walked past it, obsessively talking about it to my partner: the flapper-era figure recalled the image of Marcel Duchamp dressed as Rose Selavy while the large halftone dots constituting the reproduction reflected the pattern of the hat veils. Recognizing that original 19th-century photographs were an integral component of advertising and merchandizing, how did photomechanical imagery impact visual culture? Could 3-dimensional photo objects be incorporated into the canon? Did photography also have a sculptural identity? The first historians, Josef Eder, Beaumont Newhall and Helmut Gernsheim resisted such a parallel social history to focus on the medium’s fine art applications. Finally, it also didn’t escape me that my paternal grandmother was a hat designer. So, after some consternation, I decided to buy the article. Living with something, the exercise of interacting with it on a daily basis, was one method of meditating, if you will. The notion of a different form of display (since the customary 20th-century attitude of viewing photographs was on the wall), was an important consideration in examining this material.

MH: I love the range of your collection. Certain pieces literally make me laugh out loud. But they all make sense with in the framework of Pop Photographica. Did you start surprising yourself with the material you included?

DK: Building my collection was chock-a-block with surprises. “Trajectory” is a dynamic word but, honestly, it’s only appropriate in retrospect. An orderly, progressive path seemed elusive when I was started out. After all, collecting is not like shopping, it is an organic process that moves (lurches?) in stops and starts.

The experience of looking at some of the funkier works and laughing out loud is familiar to me, too. In fact, having fun with this was a positive sign when I was openly questioning the validity of collecting as a creative act. Perhaps it’s odd to admit this, but I experienced plenty of anxiety at the outset. After all, I was operating in unknown territory with no foundation or structure to dip into. Needless to say, the first few acquisitions were akin to seeing in the dark, I sensed something was there but, I couldn’t articulate what it was.

Finding a post-modern photographic discourse was part of my new job as a collector. Someone mentioned Michel Braive’s book, The Photograph: A Social History, along with Robert Sobieszek’s The Art of Persuasion were important building blocks. John Wood introduced me to two wonderful and generous scholars, Heinz and Bridget Henisch, who wrote extensively about “the photographic experience.” At Swann, a client brought in a classic “how-to” book, Frank Fraprie’s and Walter Woodbury’s Photographic Amusements. This illustrated volume, probably one of the best-selling photobooks of all time — which was in print continuously from 1893 to 1938 — was an epiphany. Conversations with Geoff Batchen, who interviewed me about vernacular photographs for an issue he edited of The History of Photography, were also instrumental.

The interdisciplinary nature of pop photographica should also be mentioned. It was obvious that many of the photo objects crossed over into Americana (folk art, outsider art), Decorative Arts, Contemporary Art, Classical Photography and Material Culture. In addition, although they’re not specifically “design-y,” many of the functional items are beautifully designed. Thus, I drew from methodologies in related fields: taxonomies employed in folk art that Margit Rowell eloquently writes about, as well as early photographic history relating to the first photograph, the daguerreotype.

Daguerreotypes are unique objects that are secured into beautiful leather cases, which resemble miniature books and fit neatly into the palm of one’s hand. Interestingly, most of the makers of daguerreotypes are unidentified or uncredited. Also, viewing a daguerreotype — which is a silver coated copper plate that shifts from negative to positive depending on the angle of vision — is a full body, sensory experience. Some collectors refer to daguerreotypes as the first holograms. The idea that the photograph is a component of the object, that one intentionally engages with this article by removing it from a drawer or a mantel and opening the case (in other words, it’s not typically displayed on the wall), underpins Pop Photographica.

MH: In the folk art arena there is often a lack of attribution: here, critics have loosely adopted a system sometimes referred to as Good, Better, Best, which came from grading American furniture, where items tended to be classified on the basis of bells and whistles. Do you do that as well? I am thinking specifically about two 19th Century objects: the Civil War checker board and the Voos playing cards that are illustrated in your exhibition catalog Pop Photographica: Photography’s Objects in Everyday Life, 1842-1969? Would you consider grading these hierarchally as “best”?

DK: I don’t find that sort of grading system useful, especially in light of some of the contemporary artworks produced today. I’m looking to create dialogues, intra-relationships between objects in my collection in addition to connections between these pieces and works by modern and contemporary artists. One could attribute the notion of assigning grades to anonymous works as a failing. Perhaps a reason why such hierarchies were employed in folk art is because the makers are largely unknown; hence there’s no branding mechanism. But what if collectors, curators, and viewers could appreciate a work of art without being dependent on knowing the artist’s name? It’s that sort of visual literarcy — the ability to navigate an increasingly pictorial world — that is incumbent upon us today.

MH: People take photography seriously in the historical and fine art fields. In your collection, you aren’t so much thumbing your nose at the established standards for excellence as you are venturing beyond those ideas and taking a break from a narrow focus: you’re really looking at how photography exists — and is used — in the world. How has your background in historic and fine art photography helped to inform your collection?

DK: I’ve been interested in broadening our understanding of what constitutes photography, to explore the relationship between “high” and ‘low” culture. In 1990, Kurt Varnedoe and Adam Gopnik co-curated an exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, High and Low: Modern Art and Popular Culture, which wasn’t particularly well-received. Nonetheless, they cleverly articulated a new thesis: high art doesn’t trickle down into popular culture, rather, the opposite is true. For example, modernist photographers like Moholy, Kertesz and Rodchenko are positioned as introducing a new “visual language,” in which skewed angles, blurriness, superimposition and overhead perspective define the modernist idiom. But, what are the origins of this vocabulary: the snapshot! Anyone familiar with George Eastman’s Brownie Box camera, which was first manufactured in 1888 and popularized in the 1890s, knows that this type of imagery was not only common but thought of as the “mistakes” associated with amateur picture-making. Visual artists repositioned this idea, transforming it into a new way of seeing.

I’ve been working with this material for almost 20 years, a full cycle in the life of a collection. In the beginning, my focus was on expanding photographic history. But, in the past few years, I’m more interested in moving classical photography out of isolation to connect more directly with modern and contemporary practices. Man Ray produced numerous photographic objects (think of the metronome), as did Abbott, Duchamp, Cornell, Rauschenberg and Kienholz. Also, Faith Ringgold’s marvelous quilts and Robert Heinecken’s extraordinary photo objects have been also largely overlooked as objects that expanding the photographic experience. Countless contemporary artists like Hirst, Muniz, Mapplethorpe, Sherman and Parr have also explored this form. Perhaps pop photographica can serve as a bridge between the classical and contemporary art worlds.

MH: How did the Ansel Adams image end up on a coffee can?

DK: It’s my understanding that Adams was approached by the Hills Brothers coffee company, a California-based corporation, about licensing his picture, Winter Sunrise, Yosemite Valley. The point was to have the image highlight 3-pound and 5-pound coffee cans, which were commercially manufactured. Interestingly, there aren’t many examples of this tin — which was a disposable consumer object — available today. A client asked me to find a vintage or modern print of the picture for his collection (which he wanted to display next to the tin), I was not able to locate a single copy. Dealers who specialize in Adams’s works confirmed that prints are quite scarce.

Apparently, Hills Brothers may not have actually produced a full run of product. In the past decade, “flats” or unmoulded versions of the picture (on metal), have sold at Swann. Because Adams’s picture was reproduced in sepia-tone, it has a decidedly 19th-century appearance (equal parts Muybridge and Watkins).

MH: Alfred Stieglitz once said “Give every man who claims to have a message for the world a chance of being heard”. To me, this seems to sum up the impetus behind your collection. Are you looking to expand the discussion about photographic history, or is this a much more personal endeavor?

DK: My personal wish is to see the worlds of art and photography made more accessible. In a broader context, I’m looking to convey the excitement associated with pictures, which have enhanced my life enormously. There’s a lot of focus on literacy in our society. But, in my capacity as a photographs specialist, I work with people from all walks of life and see how woefully visually illiterate most of them are. I’m not speaking

about familiarity with particular artists or icons of fine art. I’m simply referring to the ability to “read” photographs and navigate an increasingly ubiquitous universe of images. Stieglitz’s world was quite a rarified one, I don’t think he could imagine how dominant images have actually become.

MH: What’s next? Do you have any plans for your collection at this time?

DK: The collection is now housed in a semi-public space that’s open by appointment. When I imagine the next stage of my life, I see a bigger space in which other collections are also displayed: snapshots, photojournalism, family albums, abandoned photo studio inventories and political memorabilia — to name a few. I envision a fun, special environment, which is tactile and aural, a social as well as a cultural setting, where visitors are encouraged to hang out and process their experiences. Museums are often too static, so creating a site in which Pop Photographica gets to stretch its legs would be great.

Observed

View all

Observed

By Michelle Hauser

Related Posts

Design Impact

Alexis Haut|Education

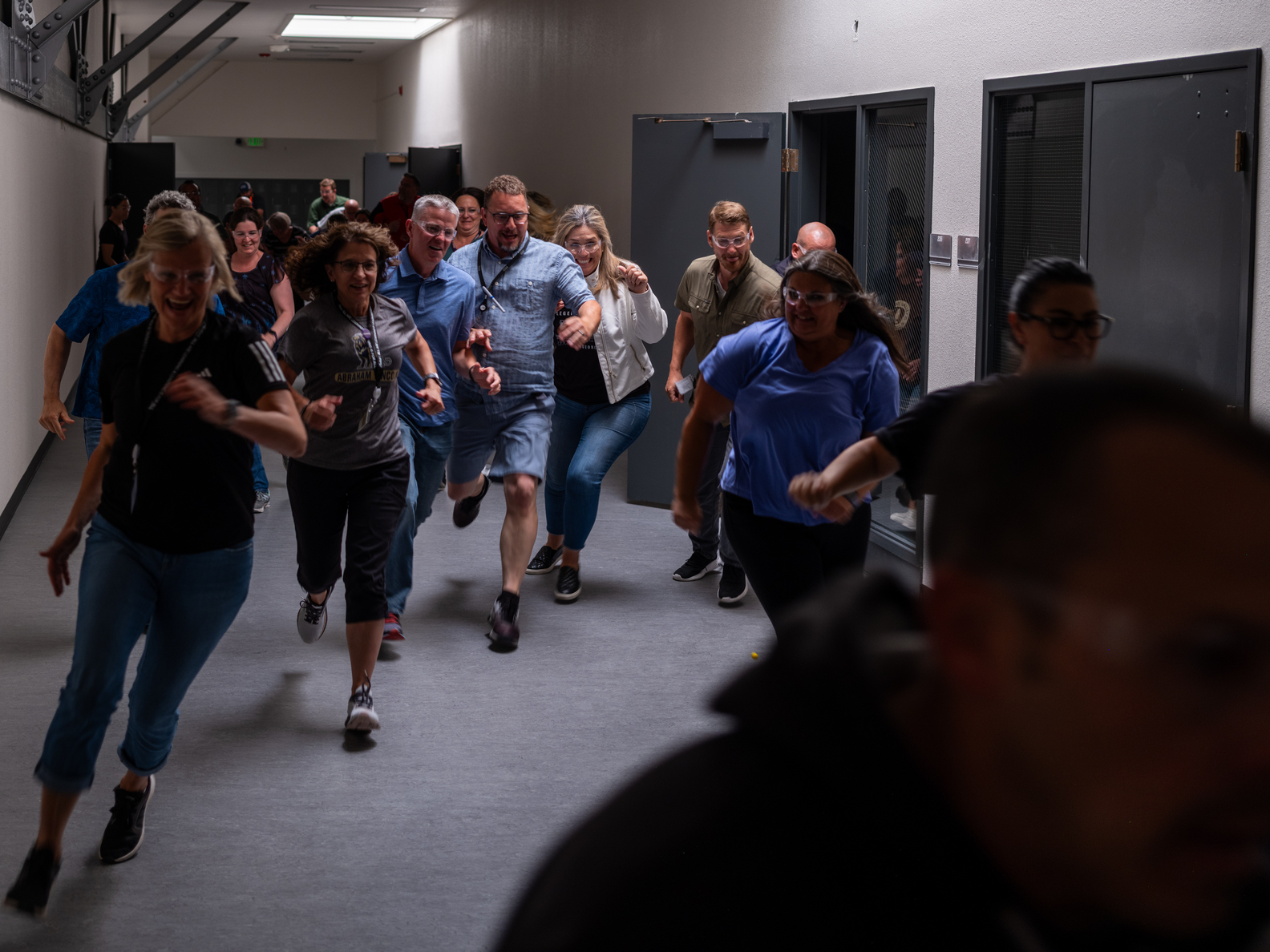

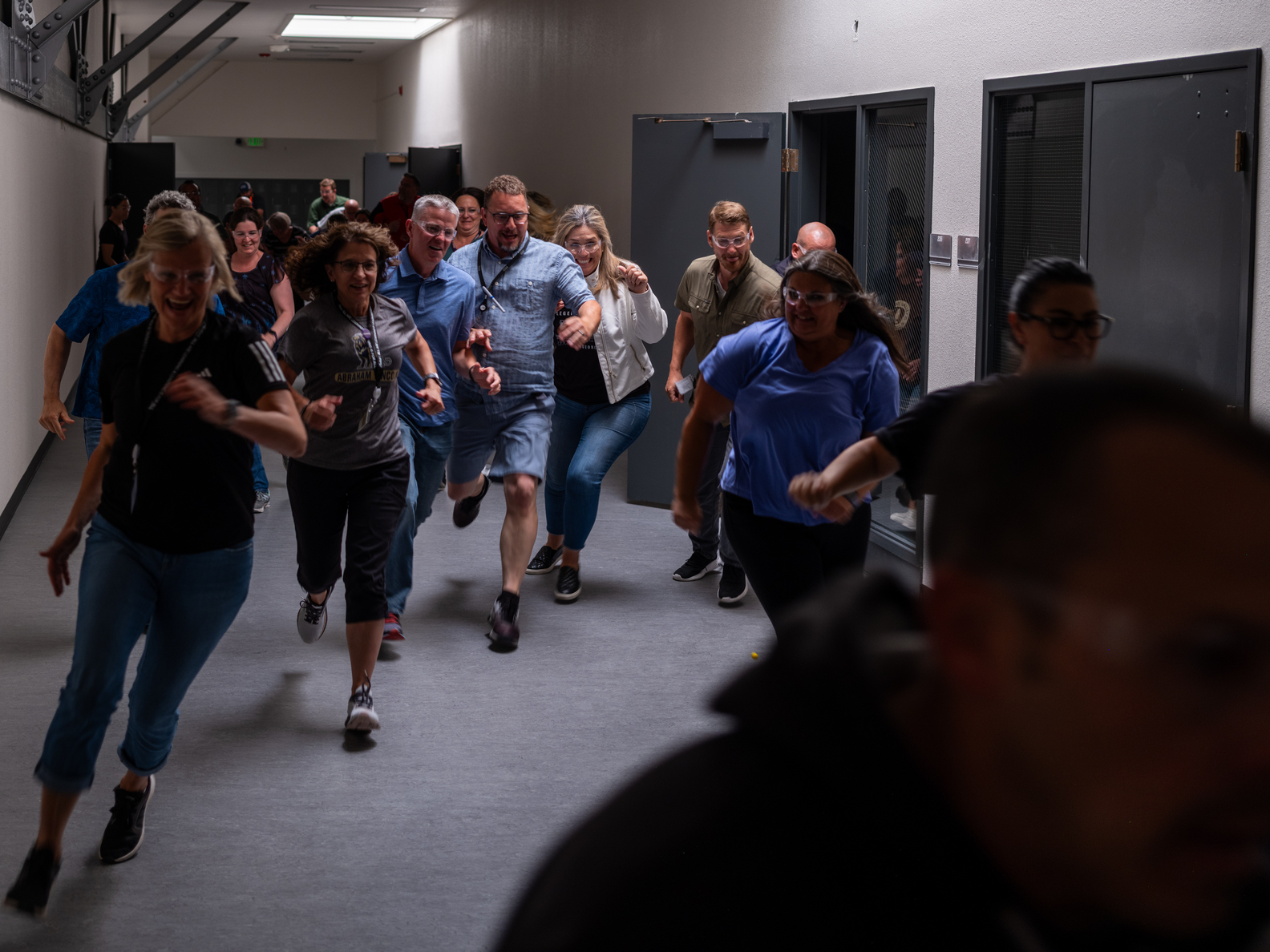

‘Thoughts & Prayers’ & bulletproof desks: Jessica Dimmock and Zackary Canepari on filming the active shooter preparedness industry

Design Juice

Ellen McGirt|Interviews

Making ‘change’ the product: Phil Gilbert on transforming IBM from the inside out

Arts + Culture

Alexis Haut|Interviews

How production designer Grace Yun turned domestic spaces into horror in ‘Hereditary’ and heartache in ‘Past Lives’

Arts + Culture

Alexis Haut|Interviews

Beauty queenpin: ‘Deli Boys’ makeup head Nesrin Ismail on cosmetics as masks and mirrors

Related Posts

Design Impact

Alexis Haut|Education

‘Thoughts & Prayers’ & bulletproof desks: Jessica Dimmock and Zackary Canepari on filming the active shooter preparedness industry

Design Juice

Ellen McGirt|Interviews

Making ‘change’ the product: Phil Gilbert on transforming IBM from the inside out

Arts + Culture

Alexis Haut|Interviews

How production designer Grace Yun turned domestic spaces into horror in ‘Hereditary’ and heartache in ‘Past Lives’

Arts + Culture

Alexis Haut|Interviews

Michelle Hauser is a visual artist living in Maine. Along with her partner, Andrew Flamm, they founded

Michelle Hauser is a visual artist living in Maine. Along with her partner, Andrew Flamm, they founded