Brian Collins, J.A. Ginsburg|Opinions

April 25, 2023

Resilient Futures: The Challenge

“Plastic Recycling, Tondo Landfill Philippines” by Adam Cohn.

As part of Design Observer’s Twentieth Anniversary coverage, we are inviting our partners to reflect on the urgent questions framing design in contemporary culture. From insights on business to studies of the environment to opinions on technology, art, and politics, these varied perspectives speak to design’s broader implications with regard to culture and citizenship, innovation and leadership, humanism, craft, and the critical values guiding our work. As ever, we welcome your comments. —The Editors.

For the last quarter century, design thinking has dominated how companies have understood the process of design and, more to the point, measured its value. Design in this context was frequently reduced to skill sets and tool kits and deep dives, sold successfully to eager C-suite executives as an innovation process that almost anyone (but certainly anyone with an MBA) could quickly master.

Yet design thinking, with its signature explosions of pastel Post-Its® plastered onto whiteboards, all too easily (and far too often) devolved into endless brainstorming sessions, popularity contests, and consensus thinking: the self-satisfied wisdom of a captive crowd. Add to it a blinkered human-centric focus, and you’ve got the perfect set up for reductionist disaster.

It ought to be obvious (table stakes) that the products, services, experiences, systems, environments, and organizations we design should enhance comfort, improve productivity, extend capabilities, or in some other way deepen and enrich our lives. This is true whether it’s the design of a coffeemaker, a company, a typeface, a transportation network, or a new neighborhood.

But once human-centric is enshrined as the goal, every other concern shifts to a lower priority. It strips out context. Combine human-centric with design thinking, and the field of view narrows to solve for one single thing, oblivious to all kinds of potential collateral damage. This negates a far more trenchant common wisdom: that we—and the products, services, and systems we create—are not a zero-sum game so much as part of a much greater whole.

Consider, for example, the curious seduction of plastic. A plastic bottle checks all the human-centric boxes: it’s cheap, light, unbreakable, sanitary, and portable. But its near-indestructibility also introduces a pervasive noxious threat. Recycling—or greenwishing? Global recycling rates have never risen beyond single digits, which translates to an excess of plastic waste, piling up everywhere from the Mariana Trench (the deepest spot on earth) to the top of Mount Everest. Every ocean has massive, lethal, swirling gyres of plastic “garbage patches,” while lakes, rivers, and streams stockpile tens of trillions of tiny poisonous petrochemical particles. Plastic has even begun to infiltrate rocks, with worrisome implications for the planet’s geologic future. Simply put: microplastics now reside in everything. Including us.

These are confounding problems, requiring careful solutions. It just isn’t enough to seek better answers, although there are a lot of better answers. Nor is it enough to broadcast “ideas worth spreading,” although that, too, can be useful. What we need are companies and organizations to seek—and find—solutions that are not only better, but solutions that are actionable. If we keep repeating the same practices, turning to Post-Its® to groupthink our way out of this mess, we will never get out of this mess.

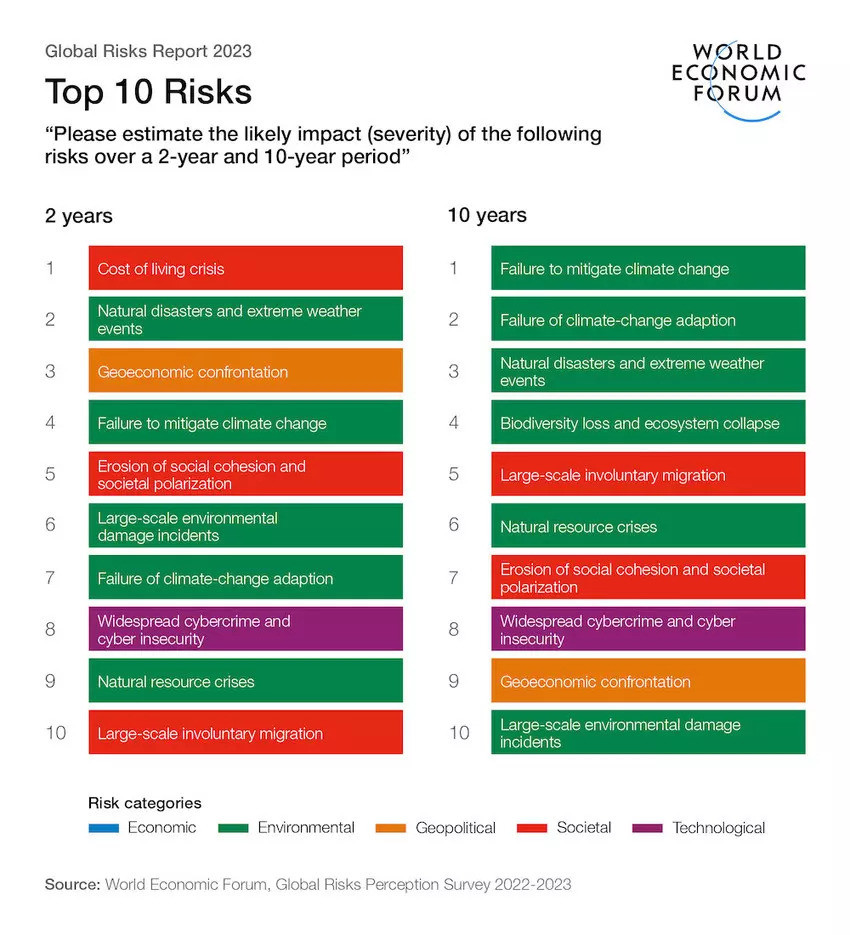

Design is thinking: so let’s reposition the challenge. Our job as designers is to help companies and organizations see, create, and communicate their rightful roles in the future, which effectively means that we have to look beyond the stakeholders of today. We have to consider who will be the stakeholders two, five, and ten years from now.

But even before stakeholders, we need to think about stakes.

Next: defining the stakes.

Observed

View all

Observed

By Brian Collins & J.A. Ginsburg

Recent Posts

The New Era of Design Leadership with Tony Bynum Head in the boughs: ‘Designed Forests’ author Dan Handel on the interspecies influences that shape our thickety relationship with nature A Mastercard for Pigs? How Digital Infrastructure is Transforming Farming and Fighting Poverty DB|BD Season 12 Premiere: Designing for the Unknown – The Future of Cities is Climate Adaptive with Michael Eliason