Maria Giudice, Christopher Ireland|Books

December 11, 2013

Rise of the DEO

Editor’s Note: This excerpt from Rise of the DEO was published with permission of the author.

Change

The crowd at SXSW stretches to the horizon. The two-week-long conference showcasing music, film, and interactive talent attracts a young crowd. Mostly under 40, the attendees come from around the globe for a hit of their favorite drug: change.

Change used to be much less popular. In business, it was an outcome: the result of deliberate, often measured efforts to reach a new goal or solve a significant problem. Considered inherently risky, it was administered in small doses. We welcomed a refreshed logo or name. A minor feature could be advertised as “new and improved,” but largescale change signaled distress. Big change meant something was wrong. Big change meant someone had erred.

Today, while change retains its prescriptive quality in some circumstances, for most businesses, and certainly for the 60,000 paid attendees at SXSW, it’s in the bloodstream.

No organization is static right now. Even the most staid and conservative company changes simply by staying the same while everything around it evolves. Traditional companies become dated companies through no effort of their own. They become the 1950s suburban ranch home surrounded on all sides by updated remodels — their safe, traditional stance slowly but surely lowering their value.

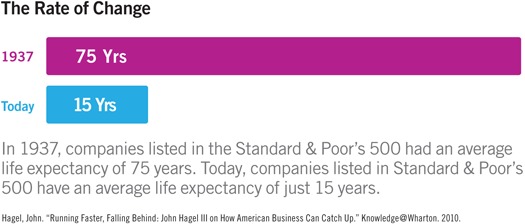

In the United States alone, over six million startups are launched annually. Google, Comcast, Amazon, Cisco, and Oracle are well-established Fortune 100 companies, yet none of them were on that list ten years ago. Twitter, Facebook, YouTube, and Pinterest connect billions of people around the globe. All were founded within the last decade.

This turbulence naturally impacts employment and careers. The conventional map of success — get a degree, start at the bottom, network aggressively, follow the rules, climb the ladder, retire comfortably — is now a no-man’s-land.

The average adult worker in the United States holds more than 10 jobs in a lifetime. It’s become increasingly common to hold more than one job at a time, to reeducate yourself continuously and to reinvent your career three to four times. The simple inquiry “what do you do?” has become a complex question unanswerable with a simple title or function.

This chaotic landscape of constant and continual change is at odds with the established view of

business and business leaders, particularly CEOs. Good CEOs once ruled from a position of stability. They commanded forces of people, money, distribution networks, and brand imagery, bolting them together into a profit-making, market-share-gaining machine. An industry might be cutthroat, but it was understandable and advanced relatively slowly. Innovations required years of development. Aspiring CEOs wrote five-year business plans, built brand equity, assembled their associations, and climbed up a well-defined hierarchy.

As attractive and permanent as that world may sound, it simply doesn’t exist anymore and it isn’t coming back.

We live in a time where little is predictable. No career path is predetermined. No one can play it safe. The majority of companies, their employees, and their leaders navigate a space where competitors appear overnight, customers demand innovations monthly, business plans rarely last a full year, and career ladders have been replaced by trampolines. This environment of incessant, nonlinear change will only accelerate in the future. Traditional CEOs are ill-equipped to survive.

Design

We’re not the only ones to see this leadership gap.

In 2010, the IBM Global CEO Study announced, “More than rigor, management discipline, integrity

or even vision — successfully navigating an increasingly complex world will require creativity.” Two years later, it added three more essential traits: “empowering employees through values, engaging customers as individuals, and amplifying innovation through partnerships.”

Daniel Pink takes a holistic perspective and relabels our era the “conceptual age.” As a result, CEOs need to be storytellers, big-picture thinkers, and empathetic humorists capable of giving meaning to our lives through their products, services, and management styles — not to mention their honest, revealing, re-tweetable posts.

Thomas Friedman warns that we’re living in a hot, flat world where a successful CEO must upload, outsource, and offshore. Tom Kelley and David Kelley invite us to reclaim our creative confidence, while Sheryl Sandberg instructs us to “lean in.”

Some authors and advisors focus attention on the problems, noting that today’s challenges are “wicked” and defy conventional solutions. CEOs, we’re told, need to change their character and develop peripheral vision, pattern recognition, an experimental mindset, and a high panic threshold.

A logical response to these avalanches of advice is to surrender. We throw up our hands and hope our inherent traits or some measure of luck will suffice. Perhaps we’ll work for the right startup, or get the attention of the right boss, or happen upon the right industry in its earliest stages. Maybe we’ll stumble across a mentor who can help us make sense of conflicting paths and tortuous routes.

Another response — the one advocated in this book — is to identify the business function best suited to these tumultuous times and use it to guide your actions. The business world has done this before. When companies needed to develop procedural discipline, it turned to Operations as a guide. When companies needed to attract and retain customers, Marketing led the way. When companies needed to learn how to scale, Finance provided the tools and perspective.

Now that companies need agility and imagination, in addition to analytics, we believe it’s time to turn to Design as a model of leadership.

If you want to start a contentious, circular debate among a group of sophisticated, otherwise mature adults, ask them to define “design” as a business function. Google lists over four billion entries. Wikipedia adopts a particularly lame dictionary definition: “Design is the creation of a plan or convention for the construction of an object or a system (as in architectural blueprints, engineering drawings, business processes, circuit diagrams and sewing patterns),” then makes it worse by adding that no real definition exists.

The International Council of Societies of Industrial Design gives it credit for creativity, but then complicates it with grandiosity: “Design is a creative activity whose aim is to establish the multi-faceted qualities of objects, processes, services and their systems in whole life cycles. Therefore, design is the central factor of innovative humanisation of technologies and the crucial factor of cultural and economic exchange.” Phew. Good to know.

A more recent definition from proponents of design thinking emphasizes design as problem solving that creates new, useful products, places, communications, or experiences. We have no argument with this description as long as problem solving is understood to be a process and not the literal definition of design (surely we can build on successes or enhance desires as well as solve problems). We would add — with emphasis — to design is to encourage collective change.

When we think design, our first association is change: change that responds to need, embodies desire, pursues a stated direction, and reflects a shared vision. Those who are designers — either through training or by nature — actively encourage and support collective change.

Historically, design changed “things.” More recently it’s changed services and interactions. Looking ahead it will change companies, industries, and countries. Perhaps it will eventually change the climate and our genetic code.

Leaders who understand this transformative role of design and embrace its traits and tenets can command in times of change. We call these leaders DEOs — Design Executive Officers — and they are our new heroes.

From CEO to DEO

Ask a recruiter to describe the characteristics of a traditional CEO.

She’ll first mention the need for an MBA and the disciplined financial perspective that degree implies. Nearly 40 percent of current CEOs add “MBA” to their collection of capitalized initials. Next, she’ll list traits associated with military commanders: authoritative, strategic, able to delegate, decisive, prepared to lead, equipped with a big-picture perspective. Finally, she’ll suggest that the ideal CEO has some humanistic touches as well: personable, charismatic, perhaps a dash of compassion.

These traits have served companies well over the past century. When assembly lines traversed the Midwest and shift workers numbered in the tens of millions, CEOs made decisions and met deadlines. When most employees were low skilled or “cogs in a wheel,” companies needed a commander at the top. They implemented order and ensured conformity.

And then the world changed.

We leaped out of the Industrial Age and buried our noses in the Information Age. By the time we looked up from our screens, we were advancing on the Conceptual Age and the business leadership traits we previously praised had started to weaken. They’d become a little creaky. They strained to be relevant.

If we could borrow Harry Potter’s invisibility cape, we’d use it to visit an executive board meeting chaired by a traditional CEO. We’d see that he follows an agenda set months before. He points to data from the past quarter. He calls on each department to report on prescribed topics. Cloaked in invisibility, we’d slip outside and wander down the hall. In a cubicle, we’d find a young manager surreptitiously checking his social networks, future stock prices, competitors’ posts, and more appealing job openings — all updated instantly in the palm of his hand.

This scenario is repeated all around the world where the gap between who the CEO is equipped to manage and who actually works for him or her grows wider by the day. Employees are increasingly higher skilled. They seek challenge and growth over security and predictability. They’re networked both inside and outside their companies. Many have direct contact with customers. They’ve grown up collaborating and iterating in school and in personal relationships. They expect leadership that understands and embraces all this.

Putting a traditional CEO at the front of a modern workforce is anachronistic. He or she is the outdated, boxy TV in an era of flat screens, the heavy-hulled yacht struggling to keep up in the America’s Cup.

How do we fill this gap? Do we put traditional CEOs on steroids or add bionic components? Do we decide that women are better suited to the job or minorities or recent immigrants? Do we declare the job irrelevant and banish it altogether?

We suggest a simpler solution. Just as we took our cues from MBAs and the military in casting the ideal CEO of the 20th century, we can look to designers — in that term’s broadest definition — to model our future leader, the DEO.

Proposing design-inspired leadership as the answer may sound delusional to some, like a zealous art teacher attacking poverty with a new color palette. But that’s a knee-jerk reaction, based largely on associations of design with discretion, luxury, and logos. A more realistic assessment confirms that design leaders usually possess characteristics, behaviors, and mindsets that enable them to excel in unpredictable, fast-moving, and value-charged conditions.

With these traits, DEOs attract and coalesce stakeholders who share their vision, goals, and values. They build corporate cultures that nurture and retain talented employees. They lead teams who learn from one another and collaborate easily and effectively. With these traits, DEOs create resilient organizations that value expertise but make room for failure — organizations able to iterate and evolve with the changes taking place all around them.

For years, business acumen and creative ability have been siloed, united only at office parties and the occasional brainstorming session. But we live in a time that requires new leadership. We live in a time that requires people who look at every business challenge as a design problem solvable with the right mix of imagination and metrics.

Observed

View all

Observed

By Maria Giudice & Christopher Ireland

Related Posts

Sustainability

Delaney Rebernik|Books

Head in the boughs: ‘Designed Forests’ author Dan Handel on the interspecies influences that shape our thickety relationship with nature

Design Juice

L’Oreal Thompson Payton|Books

Less is liberation: Christine Platt talks Afrominimalism and designing a spacious life

The Observatory

Ellen McGirt|Books

Parable of the Redesigner

Books

Jennifer White-Johnson|Books

Amplifying Accessibility and Abolishing Ableism: Designing to Embolden Black Disability Visual Culture

Recent Posts

Minefields and maternity leave: why I fight a system that shuts out women and caregivers Candace Parker & Michael C. Bush on Purpose, Leadership and Meeting the MomentCourtney L. McCluney, PhD|Essays

Rest as reparations: reimagining how we invest in Black women entrepreneurs Food branding without borders: chai, culture, and the politics of packagingRelated Posts

Sustainability

Delaney Rebernik|Books

Head in the boughs: ‘Designed Forests’ author Dan Handel on the interspecies influences that shape our thickety relationship with nature

Design Juice

L’Oreal Thompson Payton|Books

Less is liberation: Christine Platt talks Afrominimalism and designing a spacious life

The Observatory

Ellen McGirt|Books

Parable of the Redesigner

Books

Jennifer White-Johnson|Books