March 28, 2006

Santa Fe Diarist

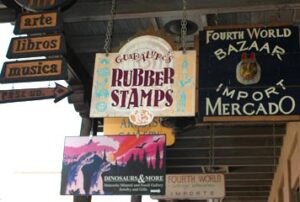

Photograph by Kenneth Krushel, 2006.

What is it about the United States that, more often than not, seems to insist upon appropriating a sense of indigenous culture, only to transform that culture into a mythological theme park? Historical interpretative creations, such as Williamsburg, Sturbridge Village, the frontier ghost town outside Dillon, Montana (and even Epcot) offer overtly educational (and to many, entertaining) re-creations of an imagined past or a foreign landscape.

But there seem to be equally vigorous efforts to commercialize this distant past, embracing a design esthetic that advertises itself as the “essence” of what had been thought to be lost. Then, in re-introducing this historical narrative, an efficient assembly line manufactures it into a commercially lucrative design creed.

Santa Fe is positioned by civic leaders and business interests as a community whose design synthesizes Native American tradition, western folklore, Spanish colonial history and an eclectic history of innovative design. Architecture is dominated by pueblo (adobe) style, allegedly inspired by the simple adobe structures used by ancient tribes. Today, a visitor’s first impression of Santa Fe is that of luxury dwellings populating the desert landscape. Real estate ads feature 10,000 sq ft. houses, described as transformational, eco-friendly, practical in dry climates, and influenced by feng shui. These behemoths are sprouting in concentric circles around the state capital, metastasizing north up the high road to Taos and south along the old Turquoise Trail, out to the formerly isolated cluster of state and federal penitentiaries, and even along the interstate leading to the Santa Fe Opera and Los Alamos nuclear research facilities. In other words, Santa Fe is engulfed. It’s too late to circle the wagons.

Ultimately, a traveler visits the central plaza area of Santa Fe. When municipal authorities introduced design ordinance, in order to preserve the original flavor of the town, some argued that what was being preserved was an artificial vision based on a fictive past. But ordinances are in place, resulting in an omnipresent design sensibility encouraging massive, round edged walls made out of adobe, flat roofs, rounded parapets (with sprouts to direct rainwater), vigas (heavy timbers) extending through walls to serve as support beams, and latillas (poles) placed above the vigas in angled patterns. There are also numerous examples of enclosed patios, heavy wooden doors, elaborate corbels, beehive corner fireplaces and nichos (niches) carved out of the adobe wall for display of religious icons, or Santa Fe-inspired figurines.

Walking through the central part of Santa Fe, I had a sense that Willa Cather was turning in her literary grave. Here, death had come not just to the archbishop, but to the entire landscape, for as she wrote, the “peculiar quality in the air of new countries vanished after they were tamed by man and made to bear harvest.” The harvest, in this instance, is a festive design providing tourists with a Hollywood back-lot of a southwestern frontier town, albeit gentrified and navigated by SUVs. Plastic luminarios and fabricated bunches of chili peppers draped over balconies remain on display throughout the year, not just for Navidad for which they were originally intended; streets are lined with shops flogging western jewelry, southwestern art, faux Ansel Adams-style photography, antiques, western inspired clothing (including $1,000 cowboy boots and $2,000 tasseled, fringed and bejeweled cowgirl ensembles), massage and holistic medicine studios, cafés serving espresso and crèpes, and even oxygen bars to help visitors adjust to the mile-high altitude.

It’s one thing for the far-flung suburbs and gated communities to invent the lost past, but here, at the very heart of the community, the epicenter of inspiration is a cenotaph to commemorate colonists who arrived 400 years ago from Mexico. Led by Don Juan de Orate, who established himself as the leader of the 500-strong travelers, the migrants created what was one of the earliest European settlements. They planted European crops, introduced the first horses, sheep, goats, cattle, donkeys, poultry, and supported a cadre of Franciscan priest and brothers who nurtured the settlers and converted the indigenous peoples. Aside the memorial is St. Francis Cathedral with a statue of the town saint, one leg lifted like a ballerina into the air, as if the saint was performing “Swan Lake.”

Nearby, art stores offer prodigious sculptures of enraptured Indian braves charging into imagined battle, and statues of Navajo warriors seemingly cathartic as they raise their arms to their pantheistic heaven. The corral of objet d’art gives a sense of collective torture, and, I suppose, demonstrates a market for high-priced paralyzed mythological forms frozen in a fantastical time and place. These sculptures are as alien to the cultural tradition as ubiquitous casinos on Indian reservations.

An hour’s drive from Santa Fe, and within minutes from Los Alamos, are the ancient ruins of Frijoles Canyon, protected within Bandelier National Monument. Following the migration of animals which they hunted, the ancients migrated in and out of the area for more than 10,000 years. Over time they became more sedentary, building at first wood and mud structures, which were later replaced by stone structures carved into the surrounding cliffs. The entrances and “windows” of these cliff homes, having endured hundreds if not thousands of years of erosion, have achieved a kind of misshapen geometric form, and without too much imagination suggest ancient ritual masks. Standing before these still and silent cliff dwellings, a traveler becomes aware of a greater presence, something ancient and seductive. There are no zoning regulations defining a heritage, no commercial venue selling cultural artifacts, no land to build upon, nothing derivative or contrived. Just something still, and humble, and in its own way, perfect.

When work is undertaken to replicate the architecture and design of a largely eviscerated cultural tradition, what is drawn from the past to define a vital present? Do we rely upon atmospherics and unearthed remnants to authenticate a sense of replicated antiquity? Is there an “orthodox” original source dictating style and sensibility, or is reinterpretation and creative invention permitted? Certainly this is a large, contentious topic, with an ongoing tension between preservationists and commercial interests. I know of no better example of this collision of interests than Santa Fe. Amidst these Anasazi ruins, there is an overwhelming sense not only of what has been lost, but perhaps more critically, of what needs to be remembered.

Kenneth Krushel is the chief executive officer of Proteus, a leading provider of wireless applications. He is a former journalist.

Observed

View all

Observed

By Kenneth Krushel

Related Posts

Business

Courtney L. McCluney, PhD|Essays

Rest as reparations: reimagining how we invest in Black women entrepreneurs

Design Impact

Seher Anand|Essays

Food branding without borders: chai, culture, and the politics of packaging

Graphic Design

Sarah Gephart|Essays

A new alphabet for a shared lived experience

Arts + Culture

Nila Rezaei|Essays

“Dear mother, I made us a seat”: a Mother’s Day tribute to the women of Iran

Recent Posts

Minefields and maternity leave: why I fight a system that shuts out women and caregivers Candace Parker & Michael C. Bush on Purpose, Leadership and Meeting the MomentCourtney L. McCluney, PhD|Essays

Rest as reparations: reimagining how we invest in Black women entrepreneurs Food branding without borders: chai, culture, and the politics of packagingRelated Posts

Business

Courtney L. McCluney, PhD|Essays

Rest as reparations: reimagining how we invest in Black women entrepreneurs

Design Impact

Seher Anand|Essays

Food branding without borders: chai, culture, and the politics of packaging

Graphic Design

Sarah Gephart|Essays

A new alphabet for a shared lived experience

Arts + Culture

Nila Rezaei|Essays