May 4, 2011

Science Gets Around to Architecture

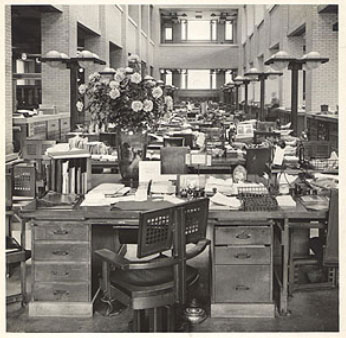

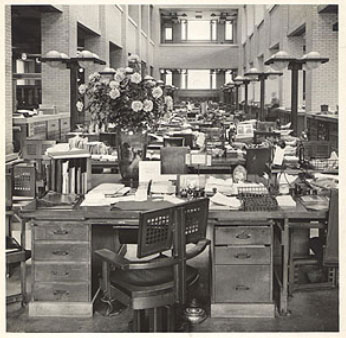

Frank Lloyd Wright, Larkin Administration Building, Buffalo, 1906.

Jonah Lehrer’s April 30 “Head Case” column in the Wall Street Journal, “Building a Thinking Room,” is the kind of mainstream reporting on architectural matters that always makes my blood boil.

For thousands of years, people have talked about architecture in terms of aesthetics. Whether discussing the symmetry of the Parthenon or the cladding on the latest Manhattan skyscraper, they focus first on how the buildings look, on their particular surfaces and style.

If this were a student paper, I would circle that people. Which people? In which decade, much less century? All people until you, Jonah Lehrer, decided it was worthy of your interest? The substance of the article is new research by scientists that show that “architecture and design can influence our moods, thoughts and health.” To which anyone involved for the past thousands of years in architecture and design can only respond, No duh. Nice of science to finally catch up.

Among the shocking new revelations: A low-ceilinged space with loud air conditioners is a more stressful work environment than a recently renovated one. Blue rooms aid creative thinking. Lehrer writes:

Although we’re only starting to grasp how the insides of buildings influence the insides of the mind, it’s possible to begin prescribing different kinds of spaces for different tasks. If we’re performing a job that requires accuracy and focus (say, copy editing a manuscript), we should seek out confined spaces with a red color scheme. But for tasks that require a little bit of creativity, we seem to benefit from high ceilings, lots of windows and bright blue walls that match the sky.

My outrage stems from the notion that this is news, or that only now, when scientists have found it to be true, can architectural knowledge be used to make the world a better, happier and more productive place. This attitude privileges scientific knowledge over visual thinking, a common and largely unexamined prejudice. Why are those smarts more applicable, more mainstream than ours? Why do we need science to codify what architects have practiced for centuries? It is not as if daylighting happened yesterday.

I haven’t been so annoyed since Lehrer’s last foray into design, the rudely titled New York Times Magazine article, “A Physicist Solves the City.” Are we supposed to thank him?

Observed

View all

Observed

By Alexandra Lange

Related Posts

Business

Courtney L. McCluney, PhD|Essays

Rest as reparations: reimagining how we invest in Black women entrepreneurs

Design Impact

Seher Anand|Essays

Food branding without borders: chai, culture, and the politics of packaging

Graphic Design

Sarah Gephart|Essays

A new alphabet for a shared lived experience

Arts + Culture

Nila Rezaei|Essays

“Dear mother, I made us a seat”: a Mother’s Day tribute to the women of Iran

Recent Posts

Courtney L. McCluney, PhD|Essays

Rest as reparations: reimagining how we invest in Black women entrepreneurs Food branding without borders: chai, culture, and the politics of packaging Why scaling back on equity is more than risky — it’s economically irresponsible Beauty queenpin: ‘Deli Boys’ makeup head Nesrin Ismail on cosmetics as masks and mirrorsRelated Posts

Business

Courtney L. McCluney, PhD|Essays

Rest as reparations: reimagining how we invest in Black women entrepreneurs

Design Impact

Seher Anand|Essays

Food branding without borders: chai, culture, and the politics of packaging

Graphic Design

Sarah Gephart|Essays

A new alphabet for a shared lived experience

Arts + Culture

Nila Rezaei|Essays

Alexandra Lange is an architecture critic and author, and the 2025 Pulitzer Prize winner for Criticism, awarded for her work as a contributing writer for Bloomberg CityLab. She is currently the architecture critic for Curbed and has written extensively for Design Observer, Architect, New York Magazine, and The New York Times. Lange holds a PhD in 20th-century architecture history from New York University. Her writing often explores the intersection of architecture, urban planning, and design, with a focus on how the built environment shapes everyday life. She is also a recipient of the Steven Heller Prize for Cultural Commentary from AIGA, an honor she shares with Design Observer’s Editor-in-Chief,

Alexandra Lange is an architecture critic and author, and the 2025 Pulitzer Prize winner for Criticism, awarded for her work as a contributing writer for Bloomberg CityLab. She is currently the architecture critic for Curbed and has written extensively for Design Observer, Architect, New York Magazine, and The New York Times. Lange holds a PhD in 20th-century architecture history from New York University. Her writing often explores the intersection of architecture, urban planning, and design, with a focus on how the built environment shapes everyday life. She is also a recipient of the Steven Heller Prize for Cultural Commentary from AIGA, an honor she shares with Design Observer’s Editor-in-Chief,