December 31, 2009

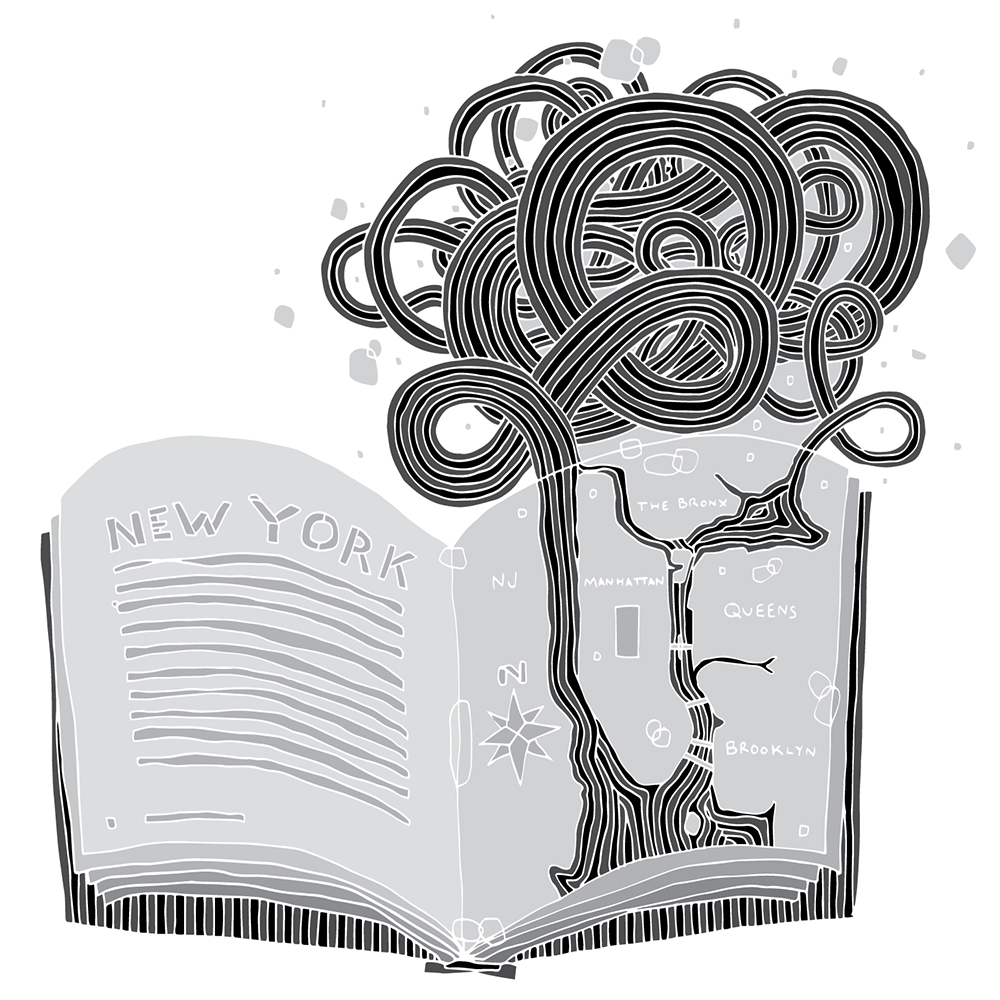

Should Book Publishing Leave New York City?

A short walk from the building where I design books for a living is Centre Market Place, a one-block street in Manhattan where my family lived for three generations. My great-grandfather started out shining shoes for his father, who was a cobbler. One day a regular customer went well beyond a regular tip and offered him a job as an elevator operator. The facts sound casual but make no mistake this opportunity was an earthquake. Over a century later that shoe shine customer’s decision to reach down and pull up Giuseppe LaRossa echoes in the good fortune of my own sons.

Giuseppe went on to become an elevator installer and eventually charged his son Joseph with the skills of an electrician. Joseph repaired elevators for Rockefeller Center, and his son Ralph, my father, became the first person in the LaRossa family to go to college, after which he went on to earn a master’s degree and a doctorate. By taking the educational elevator to the top floor, my father afforded me the privilege of following my own talents towards riskier investments—like art school.

My story is the quintessential New York City brand of the American Dream. New York City has been the catalytic stage for the generational growth of countless families, in fact whole communities; and it has done the same for businesses, in fact whole industries. Book publishing is a prime example.

In 1885, three years after my five-year-old great grandfather arrived in New York from Italy, the Boston-based book publisher Houghton Mifflin adopted a clever logo that featured an illustration of a young boy pushing paper boats into a stream. The fortunes of book publishing firms have long floated atop bodies of water. Other examples of publishing houses that have branded themselves with water-themed marks include Aldine Press; Williams Collins, Sons; Doubleday; Viking Press; Farrar, Straus, & Giroux; and Thames & Hudson. Indeed most of the English language books that have ever been printed were conceived a few blocks off the banks of the Thames or Hudson rivers, and the Hudson’s meeting with the Erie Canal primed New York City to become the beating heart of the publishing world.

“Harper Bros., one of the earliest American publishers, began as a New York printer in 1817. Soon the firm was competing with other New York printers to ship books, including pirated editions of British authors, via the Erie Canal to the hinterland, where local printers could not match New York prices. The canal gave the New York printers an advantage over their competitors in Boston and Philadelphia, which helps explain New York’s preeminence as a book publishing center.” —Jason Epstein

“Boston was a Congregationalist theocracy with strong Puritan overtones, Philadelphia was a Quaker aristocracy. But New York was polyglot, cosmopolitan, open to anyone with talent and ambition.” —Jason Epstein

Long before Harper Bros., in the ruinous wake of the Revolutionary War, the seed of New York City’s publishing trade was planted along Pearl and Water streets in the waterfront clamor of Hanover Square—the commercial epicenter of the city at that time. The lines between publishing trades were blurry back then. Early American printers sold books, book publishers printed newspapers, and both books and papers were hawked alongside fresh fish and raw oysters. The texts that were typeset in those buildings, which had only just recovered from serving as British barracks, helped define the character a young democracy.

Boston was a Congregationalist theocracy with strong Puritan overtones, Philadelphia was a Quaker aristocracy. But New York was polyglot, cosmopolitan, open to anyone with talent and ambition. John Jacob Astor, a fur trader, might have scraped by in Boston or Philadelphia. In New York he became, despite his lowly origins, his accent, and his foreign birth, the richest man in the United States and the founder of a dynasty. By the Civil War, New York’s preeminence as a publishing center was well established.” —Jason Epstein

New York’s signature hustle and bustle dates back to the Dutch trading post of New Amsterdam, which was run at the Southern tip of Manhattan by the Dutch West India Company from 1624-1664—long before the island was flattened into a grid. But the idea of New York City as a promise land, for fishmongers, elevator mechanics, and publishers alike, began in a book. In 1665 Adriaen van der Donck published Description of New Netherland, a largely promotional text designed in part to persuade Europeans to emigrate to New Amsterdam. It proved to be effective. During the 35 years following the book’s release Manhattan’s population doubled in size. In reference to the impact of van der Donck’s book, a Dutch West India Company director wrote, “Formerly New Netherland was never spoken of, and now heaven and earth seem to be stirred up by it and everyone tries to be the first in selecting the best pieces [of land] there.”

Although the story of Manhattan predates van der Donck’s book, you could argue that the city began in earnest with its printing. A book gave birth to the city even before the city began giving birth to books. And give birth it does—today the five largest English-language book publishers in the world call Manhattan home. America’s publishing trade took root and flourished in New York because the city’s cultural and geographic conditions created an optimal environment for that to happen. The book industry spilled out of the city’s equation—an inevitable outcome.

[T]oday the five largest English-language book publishers in the world call Manhattan home. America’s publishing trade took root and flourished in New York because the city’s cultural and geographic conditions created an optimal environment for that to happen.

All of that said, there’s no denying that the equation has changed—the 21st century has been host to a radical shift. The fortunes of industry now float atop bodies of data instead of bodies of water. New York City’s geography is not the strategic advantage that it once was, but this change has not diminished the value of the city’s land. The inflation adjusted median price per square foot of co-ops and condos in Manhattan has increased more than 200% since 1991—the year the World Wide Web began. There is a great deal of tension in the discrepancy between the land’s strategic value and its cost. A mighty pressure that’s putting the very idea of brand equity to the test. How much longer will the cache that comes with the name “New York, New York” outweigh the location’s financial disadvantages?

A lack of research and rampant mergers means that it’s very difficult to accurately describe the financial trajectory of the book publishing industry as a whole during the same period described above—between the start of the World Wide Web and today. But we can use the stock price of a publishing house that has remained both independent and Manhattan-based during the whole of that time as a canary in the coalmine—a rough indicator of the financial health of the publishing industry as a whole and of Manhattan-based publishing houses in particular. Scholastic, the publisher I alluded to in the first sentence of this essay, which employs me and is a few blocks from where my grandfather grew up, fits the bill. In the 27 years since the World Wide Web began, Scholastic’s inflation-adjusted stock price has increased 60%. It sounds like book publishing’s canary is still singing.

This essay was originally titled “Book Publishing Should Leave New York City,” a definitive statement that lacked the mercy of the current title’s question mark. Admittedly the working title’s firm stance was largely inspired by my first hand experience as a financially embattled resident. This is the paragraph where I had planned to expand on how being based in New York City is no longer in the book publishing industry’s best interest. How book publishers should open up to the idea of existing elsewhere. How they should leverage the remote connectivity of the cloud to tap into publishing expertise from more affordable locales in order to circumvent the financial pressures of New York’s real estate market. How those savings would buoy publishing efforts and make publishing firms more financially resilient as they continue to evolve into digital reading experience providers. But the act of writing this essay has softened that position. It appears that both New York City and the book publishing industry have been little phased by the digital revolution, and they seem to be doing just fine together. Perhaps their resilience is bound up within one another?

This is the paragraph where I had planned to expand on how being based in New York City is no longer in the book publishing industry’s best interest….But the act of writing this essay has softened that position.

In the late 1970s my father interviewed his father on tape for posterity. Recently, after revisiting those tapes, my father shared a story about one of my grandfather’s answers that I had never heard before. On the tape my father asks: So you were interested in electricity before your father introduced you to elevators? To which my grandfather replies: Yeh. I only got into elevators because it was the Depression. There was no other job. I didn’t want to go into elevators. My father: What did you want to do? My grandfather: Oh, I don’t know. At one time I wanted to write.

My father speculates that the reason my grandfather did not finish high school is that his father pressured him to drop out so he could teach his son a viable trade. As far as we know, nobody around my grandfather— not his family, or his teachers—encouraged him to write, and yet he found his way to believing the act of writing had value. I can’t help but think that living on the island of Manhattan led him to feel that way.

I wouldn’t describe the relationship between New York City and book publishing as symbiotic—that implies that they’re separate. The ideals of writing, publishing, and reading flow through the streets of Manhattan like blood through veins. These ideals breathe life into the city’s culture. Is leaving New York City in the book publishing industry’s best interest? Maybe, but I’m not sure either would survive the separation.

Observed

View all

Observed

By Brian LaRossa

Recent Posts

Courtney L. McCluney, PhD|Essays

Rest as reparations: reimagining how we invest in Black women entrepreneurs Food branding without borders: chai, culture, and the politics of packaging Why scaling back on equity is more than risky — it’s economically irresponsible Beauty queenpin: ‘Deli Boys’ makeup head Nesrin Ismail on cosmetics as masks and mirrors