March 3, 2011

Souvenirs as Nazi Propaganda

Part three in a three part series: Steven Heller on the design practices of the Third Reich. The first essay “The Master Race’s Graphic Masterpiece” and the second “Hitler’s Poster Handbook,” can be read here and here.

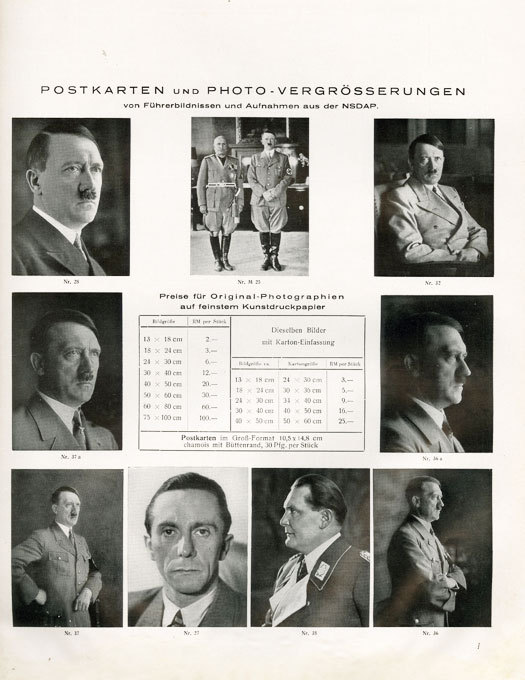

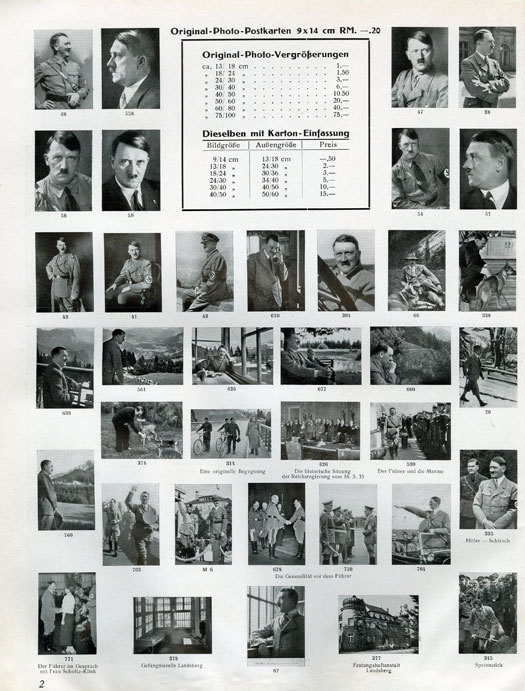

Adolf Hitler made money off design. Thanks to his personal photographer, Heinrich Hoffmann, Hitler earned one pfennig every time his face was used on a postage stamp and received royalties from all the postcards, posters and photographs using his picture that were sold to the public — and the public was encouraged to buy many and often. The funds were donated to the Nazi party, which helped pay for Hitler’s lavish mountain retreat, among other more mundane things. Actually, the majority of the royalties were derived from souvenirs — and what could be more mundane?

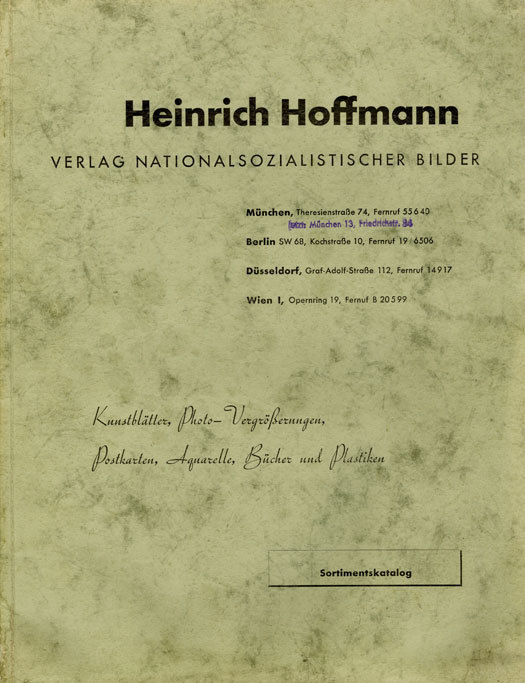

These souvenirs were primarily designed, produced and sold by Hoffmann, who in 1924 became Hitler’s documentarian and image manager. He alone was franchised to make and sell pictures, a business that became quite lucrative. By 1929 Hoffmann opened branch offices in Berlin, Vienna, Frankfurt am Main, Paris and The Hague. He further ingratiated himself with Hitler when he hired as shop assistant, a woman who dramatically impacted his future. Her name was Eva Anna Paula Braun, the 17 year old daughter of a Munich school teacher — yes, that Eva Braun.

The annual catalogs produced by Hoffmann’s attelier were printed in the hundreds of thousands. His work was sought-after throughout the Reich, if only for his exclusive access to his subjects. Of course, Germans were encouraged to distribute the hundreds of souvenirs he produced. And Nazi leaders were, obviously, pleased to be considered as subjects suitable for framing. The product range extended from every possible formal portrait of Hitler and top leaders, to informal photos of Hitler with children (in fact, many pages were devoted to “kinder”), portfolios of high quality graveur images for display and framed examples of Hitler’s watercolor art were among the replenished stock.

When Hitler became Reichschancellor in January 1933, Hoffmann’s fortunes took another positive turn. He then published his most successful book, in a series of photographic books, Hitler, Wie Ihn Keiner Kennt (The Hitler Nobody Knows), showing the leader in his home and among the people. This title made both men very wealthy. It was followed by many other profitable projects, published in thousands.

Hoffmann was an intimate of Wilhelm Ohnesorge who became Minister of the Post. Together they conceived a deal whereby Hitler was paid his postal royalty. Hitler was indebted to Hoffman and his relationship grew when Hoffmann’s daughter Henriëtte married the Hitler Jugend leader Baldur von Schirach. In 1938 Hitler appointed Hoffmann “Professor” out of respect for his craft and his artistic abilities.

Image management was profitable in many overt and covert ways. For certain fees, Hoffmann preselected works of art displayed at annual official art exhibitions at the Haus der Deutschen Kunst (House of German Art) in Munich. In 1940 he was even elected as a delegate to the Reichstag from the district of Düsseldorf-East. The world was his oyster, until . . .

The Allies imprisoned Hoffmann and tried as a Nazi “profiteer” in 1947 for producing his postcards and books. He was sentenced to ten years in prison and they confiscated nearly all of his personal fortune and his photographic negatives. He died in Munich in 1957, and his family has petitioned for the rights to his work without success.

Observed

View all

Observed

By Steven Heller

Steven Heller is the co-chair (with Lita Talarico) of the School of Visual Arts MFA Design / Designer as Author + Entrepreneur program and the SVA Masters Workshop in Rome. He writes the Visuals column for the New York Times Book Review,

Steven Heller is the co-chair (with Lita Talarico) of the School of Visual Arts MFA Design / Designer as Author + Entrepreneur program and the SVA Masters Workshop in Rome. He writes the Visuals column for the New York Times Book Review,