January 18, 2010

State of Shelter

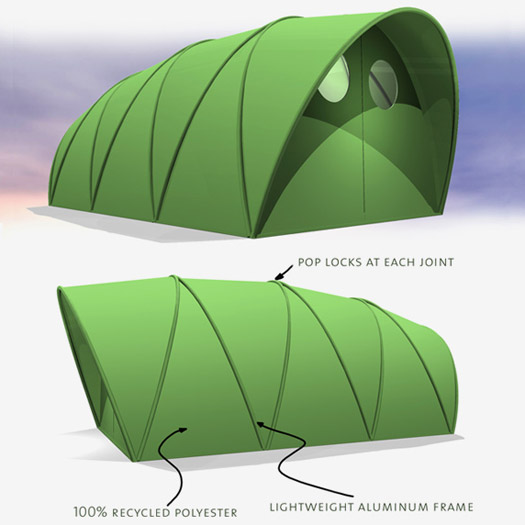

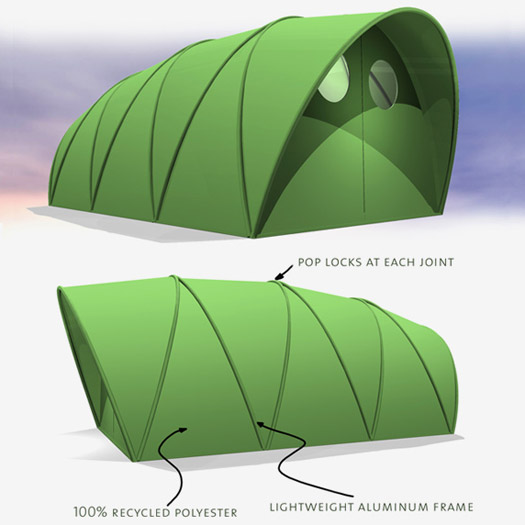

Patrick Wharram’s Lightweight Emergency Shelter. Rendering courtesy Design 21: Social Design Network.

Patrick Wharram’s Lightweight Emergency Shelter. Rendering courtesy Design 21: Social Design Network.

As aid and relief supplies reach Haiti to help earthquake victims, attention is focusing on immediate needs such as food, water, medical care and temporary shelter. Shelter plays a critical role in emergency relief as a way not only to protect victims from weather conditions but also to provide a semblance of family and community life amid horrific conditions and collapsed infrastructure.

For the most part, aid organizations still rely on old standbys like tents and tarps for emergency shelters. They are cheap and easy to transport and set up, and although basic, they work well for immediate shelter even in precarious conditions such as post-earthquake Haiti. “Nothing beats the price point of a blue tarp,” notes Deborah Gans, of Gans Studio, a New York architecture firm that has worked in the area of disaster relief housing.

There are new and innovative alternatives to tarps and tents, which have been developed over the past decade following disasters ranging from the Asian tsunami to Katrina and earthquakes in Pakistan, China and Iran. These designs use new lightweight materials, or sandbags or indigenous materials such as repackaged clay or earth. They also incorporate clever folding and packaging methods.

But the new designs have drawbacks: they are usually more expensive than tarps and tents; they have not been widely field-tested; and they are not kept in inventory in large numbers, which means overwhelmed aid agencies can’t rely on a rapid deployment. Moreover, while the newer designs can be used for prompt emergency housing they are often better suited for the second stage of relief known as transitional housing, between emergency shelters and permanent settlement.

Steps for setting up Concrete Canvas Shelter. Photos courtesy Concrete Canvas.

Compared to soft solutions like tarps and tents, the recently launched Concrete Canvas Shelters — rapidly deployable hardened shelters made from a cement-impregnated fabric — are robust and solid structures that can be erected in a few hours (all you need is water and a generator for the air pump). But they cost around $24,500 for a 270-square-foot unit, and because it is a new technology, developed by the British company Concrete Canvas, supplies are limited. Originally developed for military use and as field hospitals, concrete shelters are “probably not appropriate for Haiti as short term housing but as a replacement for infrastructure, such as for hospitals and field operations,” explains Peter Brewin, the company’s operations manager.

Deborah Gans’s Roll Out House. Rendering courtesy Gans Studio.

Concrete canvas shelters are not as expensive as the notorious FEMA trailer, used for years after Katrina to house the displaced, which cost around $67,000 each. A less expensive way to go might be Gans’s Roll Out House, made of two infrastructural columns, one of folded paper and one of bamboo, which support a roof that collects water and is equipped with photovoltaic cells. The core house could be delivered for “several hundred dollars,” Gans says, but the design, originally developed for Kosovo refugees, has never been put into production.

Global Village Shelters. Photo courtesy Global Village Shelters.

Unfortunately, the Lightweight Emergency Shelter is not yet in production (a prototype is expected this year). That’s too late to help the people of Haiti, who will have to make do right now with tarps and tents as their temporary homes as they start to rebuild their lives.

Observed

View all

Observed

By Ernest Beck

Recent Posts

Why scaling back on equity is more than risky — it’s economically irresponsible Beauty queenpin: ‘Deli Boys’ makeup head Nesrin Ismail on cosmetics as masks and mirrors Compassionate Design, Career Advice and Leaving 18F with Designer Ethan Marcotte Mine the $3.1T gap: Workplace gender equity is a growth imperative in an era of uncertainty

Ernest Beck is a New York-based freelance writer and editor.

Ernest Beck is a New York-based freelance writer and editor.