January 12, 2026

“Suddenly everyone’s life got a lot more similar”: AI isn’t just imitating creativity, it’s homogenizing thinking

Generative tools may be flattening creativity, innovation, and even self-understanding.

2025 featured a steady drumbeat of warning signs about the psychological risks of text-generating large language models (LLMs) like ChatGPT. Microsoft researchers found that generative AI reduced users’ application of critical thinking, while frightening anecdotes have shown the tools fueling paranoid delusions, divorces, scary public crashouts — including one suffered by a major OpenAI investor — and even alleged suicides and murders.

Popular image generators like Midjourney and Generative AI (“genAI”) features of design tools like Canva are based on the same basic data-processing approach as these chatbots. LLM image creation is guided by a statistical analysis of existing images, templates, and associated language in the LLM’s data set, rather than any deeper understanding of content, meaning, or aesthetics. The technology (and, often, its boosters) invite confusion between analysis and creativity, between mimicry and thought — and that confusion seems to lie at the heart of LLMs’ potential psychological risks.

Many neurologists, psychologists, and creativity experts are working to understand those risks and impacts, and there is strong early evidence that AI images can be a turn-off for the very audiences design clients are hoping to persuade. There are also hints of a much more profound risk: that the spread of generative imagery will, in stark contrast to its promise that everyone can be an artist, reduce the creativity of any society that embraces it.

The sublime ick of the uncanny

The quick evolution of LLMs over the past three years has made studying them a moving target. But one finding is very clear across multiple studies: when people think that an image was created by an LLM, they hate it.

In one Duke University experiment, subjects were told one group of “fine art” images was AI-generated, while another set of images was human-made. Subjects consistently preferred those they were told were human-made — even though, in reality, all of the images were AI generated.

“There are two ways to approach art,” says study lead Lucas Bellaiche, whose main research focus is human emotion. “The purely physical way, no critical thinking whatever, just [is it] pretty, ugly, red, whatever. And then there’s the sociocultural way: ‘what does this mean? What does it say? What is it reflecting?’ I call that the communicative mode.” Bellaiche’s study suggests that viewers are turned off by images without that communicative intent — or without at least the perception of such intent.

In 2024, researchers at the University of Turin found that, even without being told that images were generated by an LLM, viewers consistently found them “alien,” “uncanny,” and generally off-putting. Researchers compared the response to the “uncanny valley” sensation triggered by the strain of not-quite-realistic imagery, notoriously epitomized by the 2004 film The Polar Express.

The study used a now-obsolete version of the Stable Diffusion LLM image model, and some subjects’ feelings of the uncanny and strange were likely triggered by visible errors in LLM outputs — things like extra fingers.

More recent LLM models have fewer obvious mistakes to tip viewers off, but the images may still contain subtler cues that spark subconscious negative feelings. Some mistakes are less obvious than extra fingers, and could trigger a vague sense of the uncanny even if a viewer doesn’t consciously notice them. Even the AI industry, including in a recent study from OpenAI, has increasingly acknowledged that such “hallucinations” are inherent to LLMs and likely impossible to completely eliminate.

But even if all outright mistakes could be eliminated from an image generator, researchers have posited that the simplicity and “smoothness” of LLM-generated images — features inherent to the methods of their creation — could prove inescapably detrimental to the most important goal of commercial design: attracting and keeping attention.

Complexity and attention

LLM-generated images share at least one common feature: they are less complex than comparable human-created images. This relative simplicity can be seen in objective mathematical analysis of outputs, and is inherent to LLM technology. This has implications for both an image’s immediate and longer-term impact on viewers.

LLM-generated images are less complex in part because they are effectively based on an “average” of images in their training data, and are incapable of any creation beyond that data set. That can lead to stereotyped content, such as an LLM returning an image of someone vaguely resembling Albert Einstein when asked to visualize a “genius.”

But a subtler feature may be more insidious: the sheer smoothness of LLM-generated lines and gradients. LLM images “are so much more smooth than other images,” says Stanford cognitive psychologist Cameron Ellis. “There is almost no doubt in my mind that they’ll be lower complexity.”

Ellis led a 2019 study for the National Institutes of Health that tested the relationship between attention and image complexity. His work (which didn’t use AI-generated images) found that mathematically simpler images are less effective at retaining viewer attention because they are less likely to trigger curiosity and close observation.

Unlike visceral experiences of uncanny wrong-ness, we might not even notice this decline in complexity around us. Bellaiche says humans are likely to experience a “habituation effect.”

“Not to compare AI art to war, but there are a lot of horrible things in the world, and we just keep seeing them,” he explains. “We just start caring less about them.”

Individual advertisers and marketers might think about this detachment as a simple failure to retain eyeballs in a competitive environment: the simpler an image is, the less likely a viewer is to take time to consciously examine it, or its message. But for society as a whole, the concern might be the opposite: that the smoothness and simplicity of LLM products makes them all too easy to accept without thinking at all.

Complexity, cognition, and creativity

Georgetown-based neuroscientist Adam Green is among those exploring whether, as he puts it, “AI is homogenizing ideas.”

In one recent study, Green analyzed college admissions essays before and after the mass adoption of LLMs circa 2022. He found that “suddenly everyone’s life got a lot more similar” after LLMs became prevalent, even when their use was nominally forbidden. More worrying, students who used AI to write about their lives “endorse those [outputs] as being really their own story,” Green says. “Their own understanding of their life story is being homogenized. They look at this [AI-generated] essay and they’re like, this is me. That’s pretty scary.”

Homogenization of thought is scary because, Green says, people with more diverse ideas show “generally higher cognitive ability, and … they go on to get good GPAs. They have good real-world results.” Fewer diverse ideas lead inexorably to a less accomplished and productive society.

Green’s study focused on writing, and it’s already a truism among scholars and teachers that writing makes thinking more precise. But in a 2008 book, design titan Milton Glaser made a much more adventurous claim: that drawing is also part of better thinking. Glaser argued that the physical creation of an image is an exploration of ideas, and often induces a meditative flow state that can foster creativity. The physical act of drawing is also one big reason human creations contain more complexity than AI images: the shakiness or unexpected waver of a line contains the exact sort of detail and variation that draws and retains the human eye.

Another study Lucas Bellaiche contributed to, in 2023, found that even when using an LLM, professional artists created more complex and creative images than non-artists. If creatively primed human users can inject creativity into LLM imagery, the opposite is also true. Decline in experienced artists in an LLM-dominated future could become a self-reinforcing downward cycle of simplified imagery and thought, as the minds of LLM operators lose their own creative spark.

Some worry broader implications alone won’t slow the adoption of LLMs for commercial use. “I’m watching market forces not really care about those things,” says Shawn Sprockett, a working designer who assisted with the 2023 experiment. “There is a very real commercial pressure, where executives punch in a logo description and get something that’s good enough.”

But “good enough” might be very bad indeed. “Imagine being raised in a world with less diversity of [culture],” says Adam Green. “It’s unlikely that would lead to you having greater flexibility, agility, or diversity of thought.”

Instead,“it’s probably constraining the breadth of thought of a generation.”

Observed

View all

Observed

By David Z. Morris

Related Posts

AI Observer

Stephen Mackintosh|Analysis

Synthetic ‘Vtubers’ rock Twitch: three gaming creators on what it means to livestream in the age of genAI

AI Observer

Raphael Tsavkko Garcia|Analysis

AI actress Tilly Norwood ignites Hollywood debate on automation vs. authenticity

Arts + Culture

Dylan Fugel|Analysis

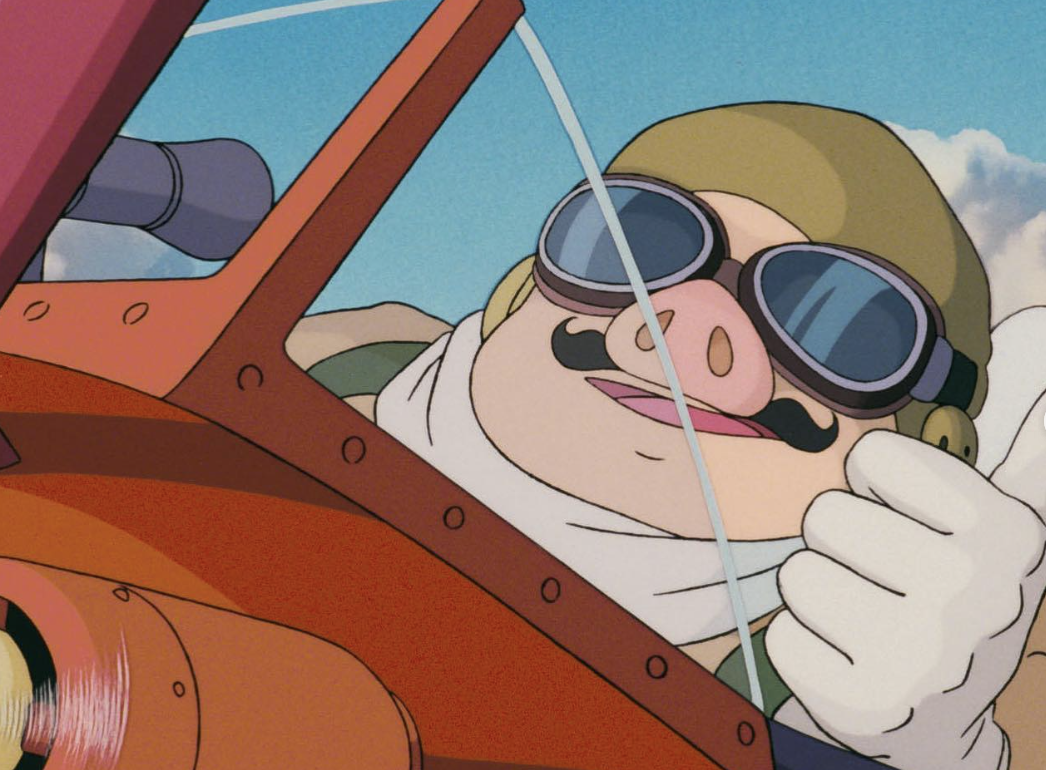

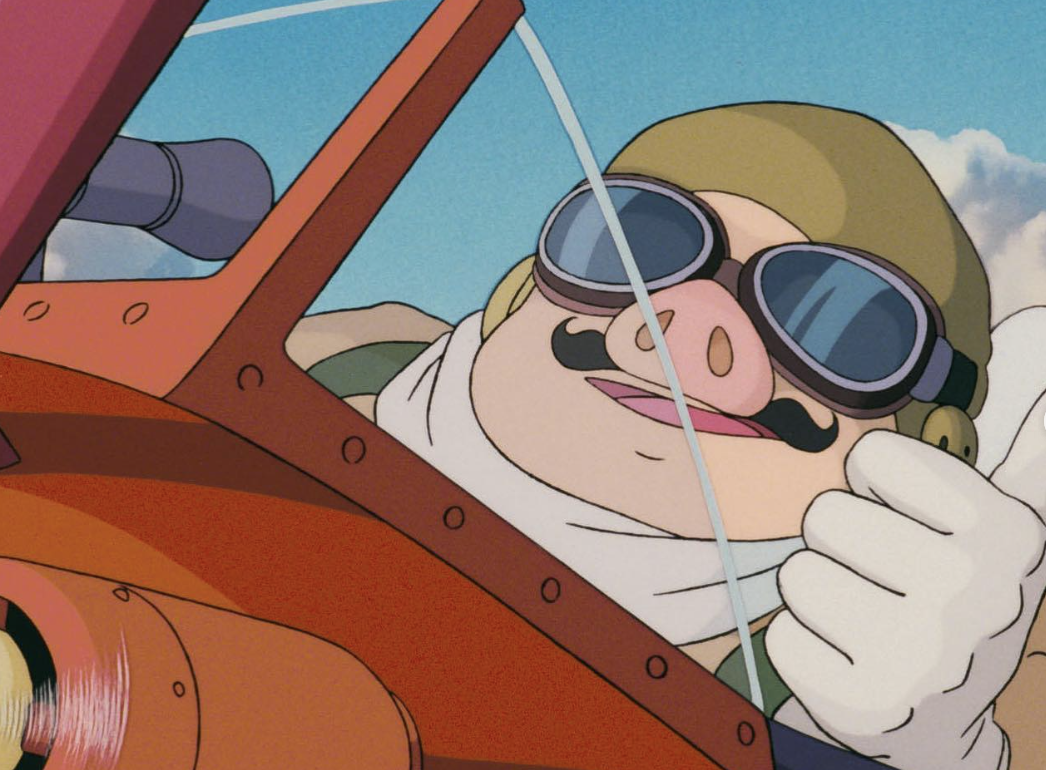

“I’d rather be a pig”: Amid fascism and a reckless AI arms race, Ghibli anti-war opus ‘Porco Rosso’ matters now more than ever

Arts + Culture

Sithara Ranasinghe|Analysis

‘Adulterations Detected:’ on the human impulse to prettify our food with poison

Recent Posts

“Suddenly everyone’s life got a lot more similar”: AI isn’t just imitating creativity, it’s homogenizing thinking Synthetic ‘Vtubers’ rock Twitch: three gaming creators on what it means to livestream in the age of genAIRaphael Tsavkko Garcia|Analysis

AI actress Tilly Norwood ignites Hollywood debate on automation vs. authenticity “I’d rather be a pig”: Amid fascism and a reckless AI arms race, Ghibli anti-war opus ‘Porco Rosso’ matters now more than everRelated Posts

AI Observer

Stephen Mackintosh|Analysis

Synthetic ‘Vtubers’ rock Twitch: three gaming creators on what it means to livestream in the age of genAI

AI Observer

Raphael Tsavkko Garcia|Analysis

AI actress Tilly Norwood ignites Hollywood debate on automation vs. authenticity

Arts + Culture

Dylan Fugel|Analysis

“I’d rather be a pig”: Amid fascism and a reckless AI arms race, Ghibli anti-war opus ‘Porco Rosso’ matters now more than ever

Arts + Culture

Sithara Ranasinghe|Analysis

David Z. Morris is a researcher and writer focused on technology’s social impacts. He is the author of Stealing the Future: Sam Bankman-Fried, Elite Fraud, and the Cult of Techno-Utopia from Repeater Books. He is also a co-founder of The Rage, a publication focused on privacy technology and policy, and a former staff writer at Fortune Magazine and former lead columnist for CoinDesk. David holds a PhD in the history and theory of communication technology from the University of Iowa, and is a former visiting researcher at Geidai (Tokyo University of Fine Arts). More of his writing can be found at

David Z. Morris is a researcher and writer focused on technology’s social impacts. He is the author of Stealing the Future: Sam Bankman-Fried, Elite Fraud, and the Cult of Techno-Utopia from Repeater Books. He is also a co-founder of The Rage, a publication focused on privacy technology and policy, and a former staff writer at Fortune Magazine and former lead columnist for CoinDesk. David holds a PhD in the history and theory of communication technology from the University of Iowa, and is a former visiting researcher at Geidai (Tokyo University of Fine Arts). More of his writing can be found at