January 1, 2005

The Collector

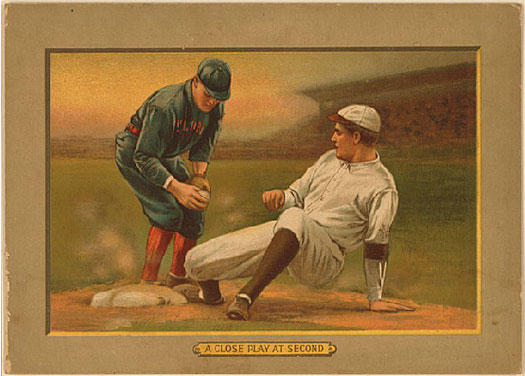

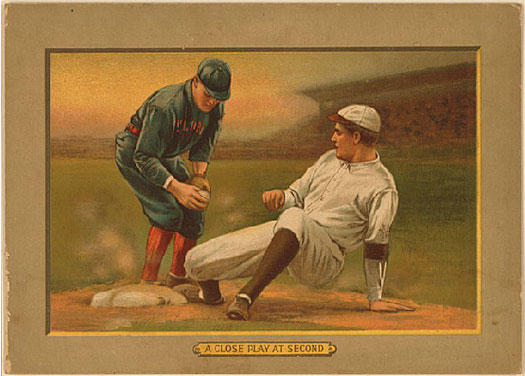

On a late fall afternoon in 1947, a frail and slightly disheveled forty-seven year old walked into the Print Department of New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. His name was Jefferson R. Burdick, and he had traveled to the city from his home in Syracuse. Burdick was a quiet, unassuming man who had lived a frugal life on a salary earned on an assembly line at the Crouse-Hines Company, a manufacturer of electrical circuits. But he had come to New York, as so many have, with a grand ambition: to convince America’s preeminent museum of fine art — a repository of priceless works of genius commissioned by royalty and bequeathed by titans of industry — to accept for its own his collection of trade and souvenir cards, most worth only pennies. At its core were some thirty thousand baseball cards; nearly every single card produced to date, and the largest collection of its kind.

It was an audacious proposition. That the museum should take Burdick’s Cobbs, Ruths, and Wagners and treat them with the same care and reverence as its Dürers, Rembrandts and Renoirs seems, in retrospect, almost like heresy. But the blue-collar collector found a kindred spirit in the Met’s blue-blood print curator, A. Hyatt Mayor. Long before the days of hundred-dollar rookie cards and high-stakes memorabilia auctions, Mayor saw the value of Burdick’s spectacular accumulation. So when Burdick offered him “the finest collection of American cards and of ephemeral printing” ever assembled, he was more than happy to accept.

Burdick had been amassing his collection for decades, rising between five thirty and six each morning to do a bit of work before heading off to his job at Crouse-Hines, and then returning to it in the evenings after coming home. Weekends were inevitably devoted to his hobby. With only an informal group of dealers and collectors for support, and without any catalog of cards to work from, Burdick was forced to spend hours on tedious correspondence, much of it to the likeminded group of men he called his “baseball boys.” By eight o’clock he was usually in bed with the paper. Lghts were out, invariably, by nine. Burdick always retired early, for he was not a well man. Chronic and debilitating rheumatoid arthritis required a full nine hours of sleep from the collector.

As it was, this painful and progressively degenerating ailment transformed him into an invalid. In fact, he had graduated from Syracuse University in 1922, but was forced to give up a job as a corporate salesman for his less physically demanding position doing intricate manual labor. Imprisoned by his own body, card collecting became the outlet for all of his energies and imagination. “A card collection is a magic carpet that takes you away from work-a-day cares to havens of relaxing quietude where you can relive the pleasures and adventures of a past day — brought to life in vivid picture and prose,” he would write in his typically elegant prose. Indeed, psychologists have often correlated obsessive collecting with physical incapacity, in particular the loss of sexual potency.

But collecting was always something more than a simple emotional balm for Burdick. It was his life’s work. “The energy that he might have put into making a home and bringing up a family, he poured instead into insert cards,” wrote Mayor. He researched the history of his cards with the diligence of an Ivy League professor, in the process becoming a pioneering and respected authority on the subject. In 1935, in his first published article, he explained to the readers of Hobbies magazine how nineteenth-century tobacco companies like Allen & Ginter, Goodwin, and Duke inserted trading cards into their packaging to help sell a new product: cigarettes. Meanwhile, his inveterate collecting made him a one-man clearinghouse of information on what other collectors were looking to buy and sell. To meet the needs of this community, in 1937 he started his own newsletter, Card Collectors Bulletin, that would bring practical information and advertising to this small group of enthusiasts. By 1939, that two-page bulletin had become a seventy-two page booklet renamed the United States Card Collectors Bulletin. Eventually, it would be published (and republished and republished and republished again) as a full-fledged hardcover book, the American Card Catalog.

The ACC, as it was then and is still known, was the culmination of Burdick’s endeavors as a publisher, and it remains a touchstone for card collectors and historians. It is, indeed, the Ur-text of card collecting — part historical narrative, part Rosetta stone, and part price guide. With the ACC, Burdick created the comprehensive catalog that he knew, from his own experience, other collectors so desperately needed. Inside, following brief descriptions and histories of the various card types, was a listing of every card set ever produced. Each of these was given a number for reference and a suggested value in dollars and cents. It was a revolutionary publication, and paved the way for the card collecting business to blossom into a modern industry. In the words of Barry Halper, the undisputed king of baseball memorabilia, “What his catalog did was to transform the informal and undocumented hobby of baseball card collecting into the more elevated rank of stamp and coin collecting.”

Ironically, Burdick rued the culture of commercialism that his ACC unwittingly produced. Indeed, one of his primary aims in creating it was to better educate other collectors in order to keep prices down. “For the good of the hobby some price schedule should be worked out,” he wrote. “I am told that certain cards have changed hands at from 50 cents to $1.00 each. I doubt the justification of such prices and I think it ridiculous to expect the hobby to thrive with such ideas in effect.”

Without deep pockets of his own, price escalation was a constant source of concern for Burdick, as Illustrated by his reaction to the sale, in 1961, of a card featuring the great Pittsburgh shortstop Honus Wagner. The card, produced in 1909 by the American Tobacco Company and known by its ACC series number, T206, was already considered the ultimate prize of card collectors. According to legend, Wagner, who was always careful about his public image, was not pleased that his picture was being used to sell tobacco, and had the cards pulled before all but a handful were shipped. (An alternate, and perhaps more likely scenario is that Wagner was simply unhappy with the financial terms offered by American Tobacco for the use of his likeness.) Whatever the case, only six of the cards were then known to exist, and Burdick had one of them, given to him by a fellow collector in the 1950s as a token of admiration. Still, he was dismissive of the $150 price paid for the card, which listed at $50 in the ACC. In a letter to a fellow collector, Burdick griped, “some kid collector asked me what it was worth in my opinion. All I can do is stick to the Catalog….There may be a small demand at over $50 but I don’t believe it’s very large.” Burdick may not have approved, but the $150 turned out to be an excellent investment. In the summer of 2000, a T206 Wagner sold at auction for $1.265 million, the highest price ever paid for a card.

Through all of his collecting and writing, Burdick’s health continued to decline. During the war, the military classed him as 4-F, “not acceptable for service.” Still, he persevered, working increased hours at Crouse-Hines to feed his collecting habit. He encouraged others to do the same, within reason. “Spend part of your spare cash on your hobby — BUT — with the rest — BUY U.S. WAR STAMPS AND BONDS,” he wrote in the Card Collector’s Bulletin.

It was, in fact, fear for his own health that spurred Burdick to visit the museum in 1947. By then he had several hundred thousand cards, and the prospect of breaking them up in some kind of fire sale was unthinkable. They were, however, stored at his home according to a system understood only by its creator. Mayor and Burdick therefore agreed that Burdick would return to Syracuse to begin the arduous task of sorting through his great accumulation, which he would then send on to the museum in parcels as his work progressed. A few months after their first meeting, in December of 1947, the first shipment arrived: a set of large albums, each weighing nearly fifteen pounds, with card after card meticulously pasted in row after ordered row. And so, for the next thirteen years, Burdick’s packages arrived on Mayor’s desk, a bounty of impossible richness delivered in anonymous brown cartons.

By 1960, however, with work on the collection still far from complete, Burdick’s illness had become dramatically worse. Injections of cortisone that he had begun taking in the 1950s were barely covering his pain. He was now too ill to continue at Crouse-Hines, and was forced into retirement. For everyone involved with his project, but most crucially Burdick himself, there was the growing specter that he might leave his one great masterpiece incomplete.

Understanding that some kind of drastic measure was necessary, Burdick moved to New York City, taking an inexpensive apartment on lower Madison Avenue so that he might be close to the museum. Mayor, who now looked upon Burdick with a combination of affection, concern, and reverence, set the collector up with a small oak desk in the Print Department. Henceforth, he would come in to sort and mount his cards at the museum every Tuesday and Friday, often with the aid of younger collectors whom he had nurtured.

Though he always maintained a benign presence in public, Burdick’s letters reveal a sense of increasing desperation after his move to the city, as his health continued to deteriorate and the prospect of completing his project was slipping away. In a letter to collector Lionel Carter in January of 1961, he reported that doctors had declared him “totally disabled.” Three months later he told Carter that he was “definitely on the down trend.” In May of 1962 he checked himself into Bellevue. “My condition was getting so unbearable that I had to do something,” he wrote from the hospital. He was released, and returned to his work at the museum in July, but he could see that the end was coming. “I may not make it,” he told Mayor.

But he did make it. At five o’clock on January 10, 1963 Burdick slowly stood up from his desk and announced to Mayor that he had mounted his final card, number 306,353 into his last album. It was his life’s accomplishment, a cause for celebration, but as he twisted his warped body into his overcoat, he seemed utterly exhausted. “I shan’t be back,” he told Mayor, and departed. The next morning, he walked the few blocks from his apartment to University Hospital. He never left. Two months later, on March 13, he was dead.

The enormous increase in card values that Burdick did so much to engender, if only accidentally, has placed a particular burden on his collection, which today occupies a somewhat awkward position within the Met’s archives. Burdick had assumed that the museum would make his collection accessible to the interested public, and as long as the public was generally disinterested it did just that. But in the 1980s, with collecting taking on an ever more mercenary character, several valuable cards were stolen and the museum was forced to restrict access. That Budick’s lumbering albums are exceedingly difficult to display has compounded the museum’s difficulties, and making things even more complicated is the fact that Burdick actually pasted his cards down onto album pages, a practice stupefying to condition-obsessed collectors that even Burdick himself repudiated. The Met albums, however, he considered an anomaly. Because he considered the museum to be the permanent home of the cards, and with duplicates provided to illustrate rectos and versos, he somehow deemed the procedure acceptable when it came to his own collection.

Today, the only hint of that great accumulation is a small, rotating display to be found in the dark recesses of the American wing of the Met. The balance — some four hundred albums — sit stacked in the museum’s darkened bowels. As for Burdick himself, his own final resting place is in a cemetery near his childhood home in upstate New York. His tombstone reads, “Jefferson R. Burdick: Greatest Card Collector Ever Known.“

Observed

View all

Observed

By Mark Lamster

Related Posts

Equity Observer

L’Oreal Thompson Payton|Essays

‘Misogynoir is a distraction’: Moya Bailey on why Kamala Harris (or any U.S. president) is not going to save us

Equity Observer

Ellen McGirt|Essays

I’m looking for a dad in finance

She the People

Aimee Allison|Audio

She the People with Aimee Allison, a new podcast from Design Observer

Equity Observer

Kevin Bethune|Essays

Oh My, AI

Related Posts

Equity Observer

L’Oreal Thompson Payton|Essays

‘Misogynoir is a distraction’: Moya Bailey on why Kamala Harris (or any U.S. president) is not going to save us

Equity Observer

Ellen McGirt|Essays

I’m looking for a dad in finance

She the People

Aimee Allison|Audio

She the People with Aimee Allison, a new podcast from Design Observer

Equity Observer

Kevin Bethune|Essays