April 6, 2016

The D Word: Inventive

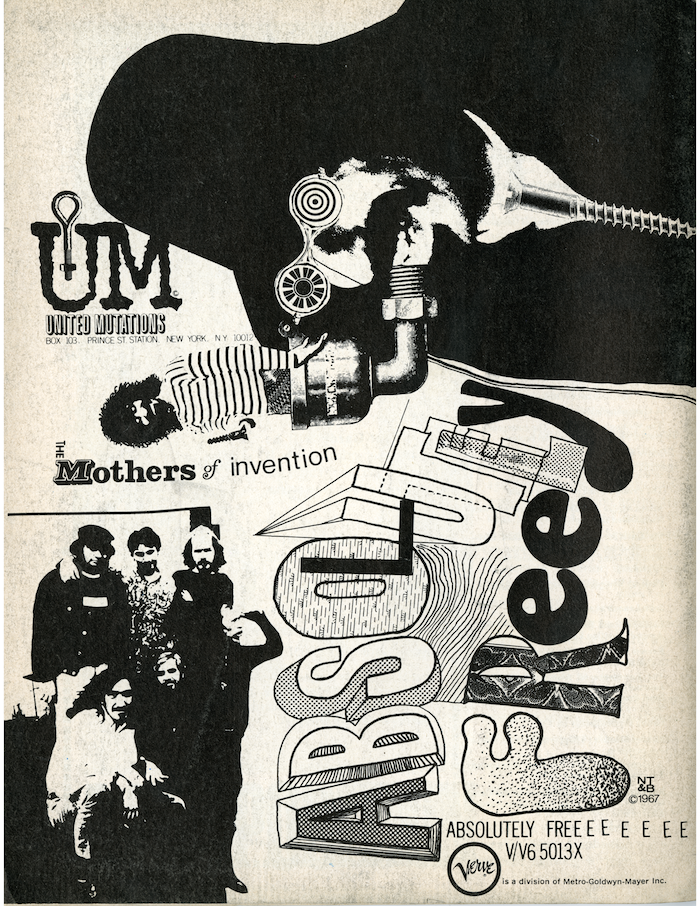

Although Verve was a division of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, one of Hollywood’s most establishment, commercial entertainment studios, the graphics for Zappa’s record cover and promotion were suitably rebellious, having spiritually borrowed from Dada and surrealist pictographic absurdity combined with the underground press’ boisterous, unschooled anarchy.

But the pièce de résistance of anti-design was the lettering for the title featuring letters that seem to emulate real display type, but also throw standards of proportion and balance to the wind. And as is often the case with hard-to-read typography (although this is perfectly discernable), the title is also set small in a light line gothic face, albeit with extra EEEEEs. As anti-establishment as it is, the ad codifies the prevailing aesthetic of the time.

Observed

View all

Observed

By Steven Heller

Related Posts

Equity Observer

L’Oreal Thompson Payton|Essays

‘Misogynoir is a distraction’: Moya Bailey on why Kamala Harris (or any U.S. president) is not going to save us

Equity Observer

Ellen McGirt|Essays

I’m looking for a dad in finance

She the People

Aimee Allison|Audio

She the People with Aimee Allison, a new podcast from Design Observer

Equity Observer

Kevin Bethune|Essays

Oh My, AI

Related Posts

Equity Observer

L’Oreal Thompson Payton|Essays

‘Misogynoir is a distraction’: Moya Bailey on why Kamala Harris (or any U.S. president) is not going to save us

Equity Observer

Ellen McGirt|Essays

I’m looking for a dad in finance

She the People

Aimee Allison|Audio

She the People with Aimee Allison, a new podcast from Design Observer

Equity Observer

Kevin Bethune|Essays

Steven Heller is the co-chair (with Lita Talarico) of the School of Visual Arts MFA Design / Designer as Author + Entrepreneur program and the SVA Masters Workshop in Rome. He writes the Visuals column for the New York Times Book Review,

Steven Heller is the co-chair (with Lita Talarico) of the School of Visual Arts MFA Design / Designer as Author + Entrepreneur program and the SVA Masters Workshop in Rome. He writes the Visuals column for the New York Times Book Review,