November 11, 2015

The Heights of NIMBY-ism

A long time ago in a galaxy far, far away, I worked for George Lucas. It was during the prequel trilogy (1999–2005), when the Star Wars culture machine shifted to light speed by cranking out countless pieces of merchandise—and, a time when the gaming industry was innovating the virtual’s relationship with other media, like film. No, I’m not the droid you’re looking for; I am not to blame for unleashing Jar Jar Binks on the world! I was too busy testing video games. In the grand scheme of the Lucas empire, it was a very low-hanging fruit job. Even though it was a thrilling time for the franchise, for LucasArts (the gaming arm of Lucasfilm), and gaming’s evolution in general, I lived on what was a poverty-line wage that depended heavily on overtime. Despite the fact that video games were helping spread the Star Wars gospel into unprecedented markets and corners of the planet (like Singapore, for instance, where Lucas eventually set up his latest campus after closing LucasArts a few years ago), many employees there at various levels felt underpaid in a place that was already nipping at the heels of unaffordability.

The Lucas-scape in the Bay Area comes with a lot of history. On the San Francisco side of the Golden Gate Bridge is the Presidio, where, since 2001, Lucas has held a ninety-year lease on coveted redevelopment property there to headquarter his main company, Lucasfilm. To the north, on the Marin County side of the bridge, is the infamous Skywalker Ranch, tucked deep in the Lucas Valley (not named after George Lucas, by the way), where for decades Star Wars‘ top brass has bunkered down. It is also where, for well over two decades, Lucas tried tirelessly to expand his campus with a second Skywalker Ranch facility, but was forced to give up due to relentless outcry and roadblocking from Lucas Valley residents, despite the fact that the Marin Planning Commission had approved the project unanimously. (Not incidentally, Lucas’s proposal to build a “movie memorabilia museum” near the Presidio was initially rejected by San Francisco, and Chicago was recently selected to host it instead.) So, it was with much interest that I listened to an excellent series from American Public Media’s Marketplace Wealth and Poverty Desk, that took a close look at a particular, if controversial, affordable housing project in Marin County called Grady Ranch.

The Lucas Valley site of Skywalker Properties’ planned low-income housing scheme, Grady Ranch

Marin is truly a region of one-percenters if there ever was one; it is a place with virtually no affordable housing, subsidized or otherwise. When finished, Grady Ranch will be a (relatively colossal) 224-unit property that will serve low-income seniors and middle-class residents with workforce housing. It will be able to accommodate 200 people, cost approximately $100–150 million, and is being developed and fully financed by none other than George Lucas himself. He has been quoted as saying something to the effect, that if he can’t do what he wants to with the property, “he wants to do something that will benefit the community.” His property company (Skywalker Properties) is partnering with PEP Housing, an enduring non-profit in Marin that has been dedicated to serving low-income seniors for nearly forty years. “Well-known in the area for his sympathetic treatment and general preservation of agricultural and rural Marin land,” wrote Curbed back in 2012, PEP’s Executive Director Mary Stompe said that Lucas is “very passionate about community and affordable housing.” It’s great to hear, and with the size of the Lucas footprint in and around the Bay Area, I think it meets a certain tolerable expectation that he would be giving back to the community in a meaningful way. Yet, behind every door of philanthropy lurks the potential for self-serving egotism.

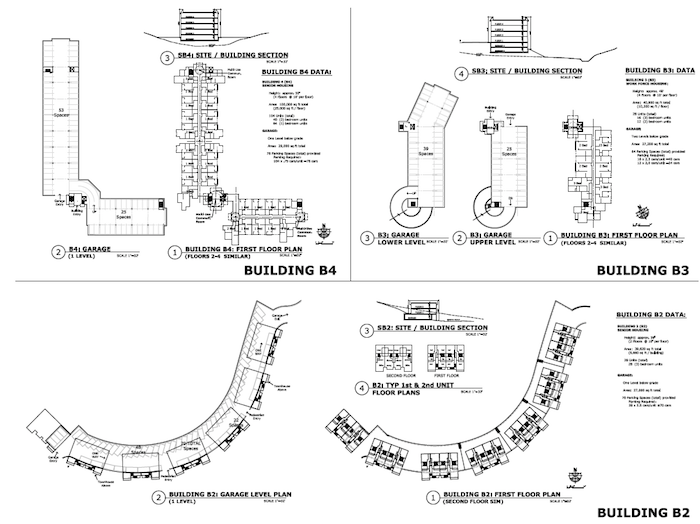

Building sections for the planned housing scheme at Grady Ranch

Building sections for the planned housing scheme at Grady Ranch

Grady Ranch happens to be slated for the same part of the Lucas Valley where he failed to expand his Skywalker Ranch facility, finally conceding that battle a few years ago. His company said in a statement: “We love working and living in Marin, but the residents of Lucas Valley have fought this project for twenty-five years, and enough is enough. … We have several opportunities to build the production stages in communities that see us as a creative asset, not as an evil empire.” And, of course, with his latest proposal, a new (but make no mistake, old) litany of NIMBY voices have announced themselves yet again in the ongoing saga between Lucas and local property owners. Marin County is considered one of the whitest counties in the Bay Area, comprised of at least a ninety percent caucasian populace. In 2009, the county was actually cited for failing to comply with 1964 Civil Rights Acts and anti-discrimination statutes mandating provisions for low-income housing that is accessible to ethnic minorities, and their participation in the process of working with federal HUD funding through non-profits.

Marin county officials have long since acknowledged this deficiency in fair housing as well as affordable housing, but still have done little to show they’ve taken the issue seriously. A more general perception of Marin is that it has done everything in its power to retain its socioeconomic purity ever since the county decided to withdraw support for BART’s expansion in the 1950s ad ’60s, a decision that may have prevented a lot of diversity and affordable housing from ever making its way in. Ever since, Marin’s lack of affordable housing has been attributed to everything from lack of suitable land in its hilly geography to a consistent increase in the cost of living to its origins as a white vacation spot that, quite literally, ran blacks out of town decades ago. All of which has played a role in the larger pattern of segregation that persists today. (Felicia Burgess, a black scholar who lives in Marin, wrote her thesis on the county’s racial segregation, and gets more into the machinations at both the residential and government level that have helped to thwart the development of affordable housing over the years.)

Listening to the Marketplace series however only confirmed my suspicions about the more cultural reasons for why Marin has ignored affordable housing. While I was completely aghast at several of the opinions voiced by those who volunteered to represent the Lucas Valley homeowners association, given what we know, none of it should come as a surprise. One stay at home dad (and “sometimes real estate agent”) in the valley said, “You know, some areas are going to be more expensive than others. I made great sacrifices to be here, I think it’s selfish to expect that someone else should be able to acquire what we take part of for little or next to nothing.” Another voice said: “It may add traffic, it might look ugly, stand out as sore thumb so to speak.” The program also featured snippets of recordings taken at a local committee meeting a few years back. One woman went as far as to say to a city council member: “Basically, it looks like you volunteered us for the ghetto.”

Classic! Regarding the property, one resident oh-so-painfully reminisced: “I think it’s beautiful. I used to ride my horse on this ranch when I was growing up. And it had cows on it.” And, as if tragic nostalgia were an elixir fed into Marin’s water supply, another resident added: “There’s trails back there that most of the people really cherish. I don’t want to see a high rise if I’m hiking back in those trails .… You think we’re not going to be able to see that thing?” But, according to the housing project’s website, the deal with Lucas “will ensure that ninety-three percent of Grady Ranch will be preserved as open space forever. Of the approximately 1,040 acres at the original Grady Ranch site, 800 were donated to the Marin County Open Space District in 2002.”

A site plan of Grady Ranch

I tend to find “NIMBY,” which merely describes a hyperlocal resistance to something, to be an empty term in that it represents very little, conjuring nothing more than another giant stereotype. In my opinion, its overuse generally fails to reveal any specific demographics of a place. However, if NIMBYism is a signifier employed by a highly privileged class, then the voices in this series not only give pure insight into the caliber of an uber NIMBYism, not to mention the atrocious politics surrounding the development of affordable housing in the Bay Area, but, captures the real xenophobia about race and poverty that remains deeply rooted in the elite pastures of California’s funky brand of “progressive” neoliberalism.

There are certainly a lot of angles to this story, and a lot of questions to consider: Is this really just Lucas doing good work, or is he mostly motivated by thumbing his nose at the locals as payback for derailing his ranch expansion? Is this project going to result in providing workforce housing for teachers, nurses, and firemen, or his own employees who currently commute to Marin from other parts of the Bay, (who, in my experience, were never paid enough to really do more than survive)? Is he just using the provision for low-income seniors as another marketing strategy to demystify the “evil empire” of the Star Wars legacy and perform some local reputation and image improvement? What happens to the small group of low-income seniors who will live there in the event Lucas decides he wants to sell the property down the line? How is permanent affordability coded into the project? Would he retain the power to evict residents if he ever so chose to?

It’s certainly rife with politics, minutiae, altruism, and ego, as are all debates about affordable housing here in the Bay Area. And, while the project is in pre-application phase, it is already playing a role in having a larger impact on the county’s progress with the goals set out in its Housing Element. But, if you want to see where the seeds of extreme anti-affordable housing NIMBYism are pleasantly sewn, just listen to the podcast.

Observed

View all

Observed

By Bryan Finoki

Related Posts

Business

Courtney L. McCluney, PhD|Essays

Rest as reparations: reimagining how we invest in Black women entrepreneurs

Design Impact

Seher Anand|Essays

Food branding without borders: chai, culture, and the politics of packaging

Graphic Design

Sarah Gephart|Essays

A new alphabet for a shared lived experience

Arts + Culture

Nila Rezaei|Essays

“Dear mother, I made us a seat”: a Mother’s Day tribute to the women of Iran

Recent Posts

Minefields and maternity leave: why I fight a system that shuts out women and caregivers Candace Parker & Michael C. Bush on Purpose, Leadership and Meeting the MomentCourtney L. McCluney, PhD|Essays

Rest as reparations: reimagining how we invest in Black women entrepreneurs Food branding without borders: chai, culture, and the politics of packagingRelated Posts

Business

Courtney L. McCluney, PhD|Essays

Rest as reparations: reimagining how we invest in Black women entrepreneurs

Design Impact

Seher Anand|Essays

Food branding without borders: chai, culture, and the politics of packaging

Graphic Design

Sarah Gephart|Essays

A new alphabet for a shared lived experience

Arts + Culture

Nila Rezaei|Essays