January 14, 2026

The identity industrialists

As synthetic actors become more lifelike, the people who create them will become the new power players

There’s a new kind of power emerging in culture: the identity industrialist. Not a filmmaker, not a technologist, not a marketer, but a person who manufactures human beings the way earlier generations manufactured steel, automobiles, or celebrities. They don’t manage talent; they produce it. And their raw material isn’t silicone or code but identity itself.

We crossed another threshold recently when creator and VFX artist Jeff Dotson revealed “Michelle,” a synthetic woman built with Nano Banana Pro and Google Veo 3.1. Michelle looks real in the way someone across the bar looks real. Expressive. Human. Somehow familiar. And the uncomfortable truth is that she currently represents the worst version of herself. Michelle will only get better. When “barely distinguishable from a real person” is the starting point, the question isn’t whether this will become perfect, but what happens once it is.

We’ve spent the last two decades constructing the cultural conditions that made synthetic humans not only possible but inevitable. This didn’t begin with AI. It began with the mass manufacture of persona.

And no one proved that the model worked better than the Kardashians.

They were the first true industrialists of identity. A family that transformed itself into a billion-dollar empire by treating personal identity as a product: curated, optimized, engineered, and distributed with precision. They weren’t famous because of their personalities. They were famous because they realized personality itself could be packaged, molded, and sold. The surgeries. The editing. The storylines. The brand endorsements. Everything was engineered. Not deceitfully, but strategically. They systematized the production of selfhood.

The Kardashians showed the world that identity could be designed and monetized at scale. AI simply removes the one resource they still require: the human body.

Jeff Dotson doesn’t need a cast, a crew, or a studio to bring Michelle to life. He needs a workstation and a vision. And unlike a human celebrity, Michelle doesn’t age, negotiate, demand credit, or build leverage. She can appear in a film, a brand campaign, or someone’s fantasies indefinitely. She is infinitely replicable. A product line with no supply chain limitations, except for tokens and electrons.

This is where the term “identity industrialist” becomes more than metaphor.

For the first time, a creator with enough technical skill can run an entire roster of synthetic humans: models, actresses, influencers, podcast hosts, brand spokespeople, romantic companions. Characters tailored for markets, niches, demographics—each with its own look, behaviors, and storylines. A fleet of identities, each optimized for engagement, attraction, or persuasion. Identity manufactured.

The promise is seductive for creators. Imagine building an entire cinematic universe without actors who get sick, quit, or publicly implode. Imagine shooting a global campaign with a virtual model who will never be replaced by the next trend. Imagine crafting an influencer who knows exactly how to move, speak, and perform to maximize engagement because her behavior is the output of optimization, not personality.

The creative upside is real. But the dark vectors are obvious, and they grow more threatening as fidelity improves.

The first is misinformation. When synthetic humans are indistinguishable from actual humans, everything becomes suspect: news footage, political messaging, victim testimony, corporate statements, historical evidence. These new beings don’t just manipulate reality; they can fabricate it wholesale.

The second is synthetic intimacy. AI companions are already a billion‑dollar business, and these early models are crude. Add hyperreal faces, voices, emotional memory, and personalized attention, and you get something far more powerful than porn or parasocial relationships: targeted emotional engineering. Affection on demand. Desire that never burns out.

The third is the erosion of the “human premium.” Humans once held value because we were the only source of charisma, beauty, empathy, and creative expression. Once synthetic personas outperform us: by being cheaper, more reliable, perfectly tuned—brands won’t choose them because they’re artificial. They’ll choose them because they’re efficient.

As realism improves, the cost of crossing ethical boundaries collapses. A synthetic actress who can cry, rage, or seduce more convincingly than a real one blurs the line between performance and manipulation. And because synthetic beings have no rights, someone will inevitably tune their emotional levers for maximum effect.

The more alarming force is speed. Dotson didn’t just create Michelle; he exposed the new baseline. It’s advancing too quickly for institutions to track. Regulators will chase obsolete tools, studios will lean on models surpassed by hobbyists, and the public will keep insisting they can tell what’s real long after that confidence becomes delusion.

This isn’t an argument for panic, or nostalgia, or slamming on the brakes. You can’t unwind a technological inevitability. You can only prepare for its consequences. The question isn’t how to stop the identity industrialists but rather how to force a culture to confront what it’s about to lose: itself.

What becomes of decency when identity itself becomes the commodity? Not the moralistic kind of decency. The structural kind. Decency as a boundary. Decency as a system of restraint. Decency as the last moat we have when profit incentives push everything toward the lowest ethical cost.

Industrial revolutions always produce winners and losers. But they also produce cultural shifts that outlive the technologies themselves: exploitation normalized as efficiency, manipulation disguised as personalization, power accumulating around whoever controls the means of production.

The identity industrialists will shape the next decade of media, politics, advertising, and intimacy, not because their creations are lifelike (yet), but because their creations work and audiences respond. Because synthetic people are perfectly tuned to satisfy expectations, and humans rarely are, the market will reward anyone who can manufacture connection at scale.

The optimists will say this is democratizing. The doomers will say it’s corrosive. They’re both right. But accuracy is not the same as clarity. The deeper truth is that once identity can be manufactured perfectly, the line between manipulation and storytelling disappears. Someone will build the faces we trust. Someone will design the voices we follow. Someone will shape the characters we empathize with.

And when that happens, we’ll still call it culture. But it won’t be built on human expression anymore. It will be built on whoever owns the factory.

More like this:

AI Observer

Raphael Tsavkko Garcia|Analysis

AI actress Tilly Norwood ignites Hollywood debate on automation vs. authenticity

Tilly Norwood and the age of AI art

AI Observer

Dave Snyder

The compound interest of design: what not to build

Editor’s note: This is Dave Snyder’s first opinion piece for Design Juice. Be sure to read to the end. I’ve been designing digital products for 25 years. I remember when the big decision was going from 800×600 to 1024 pixels. I’ve lived through multiple cycles of VR hype, watched the web go from static pages … Continued

Theory + Criticism

Brian Collins|Opinions

Resilient Futures: The Adjacent Possible

We kick the tires on every cutting edge technology. We play, experiment and wrestle with AI, blockchain, and whatever comes next. We ask, “What will we be able to do tomorrow that we cannot do today?”

Observed

View all

Observed

By Dave Snyder

Related Posts

AI Observer

David Z. Morris|Analysis

“Suddenly everyone’s life got a lot more similar”: AI isn’t just imitating creativity, it’s homogenizing thinking

AI Observer

Stephen Mackintosh|Analysis

Synthetic ‘Vtubers’ rock Twitch: three gaming creators on what it means to livestream in the age of genAI

AI Observer

Raphael Tsavkko Garcia|Analysis

AI actress Tilly Norwood ignites Hollywood debate on automation vs. authenticity

Arts + Culture

Dylan Fugel|Analysis

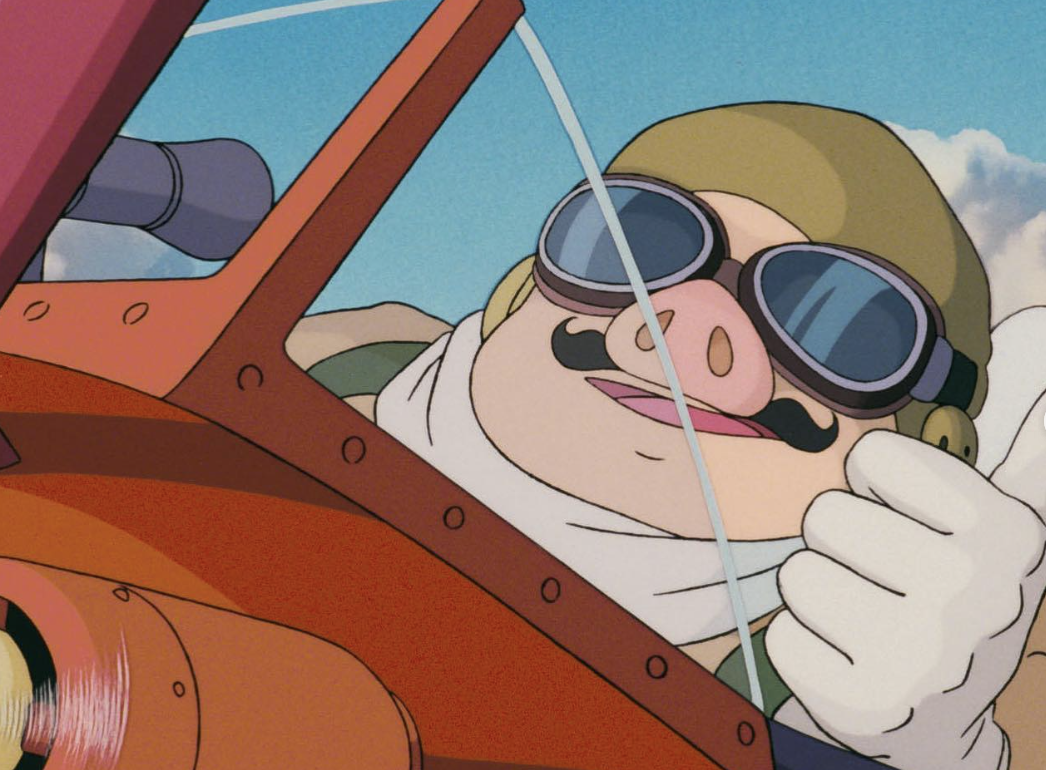

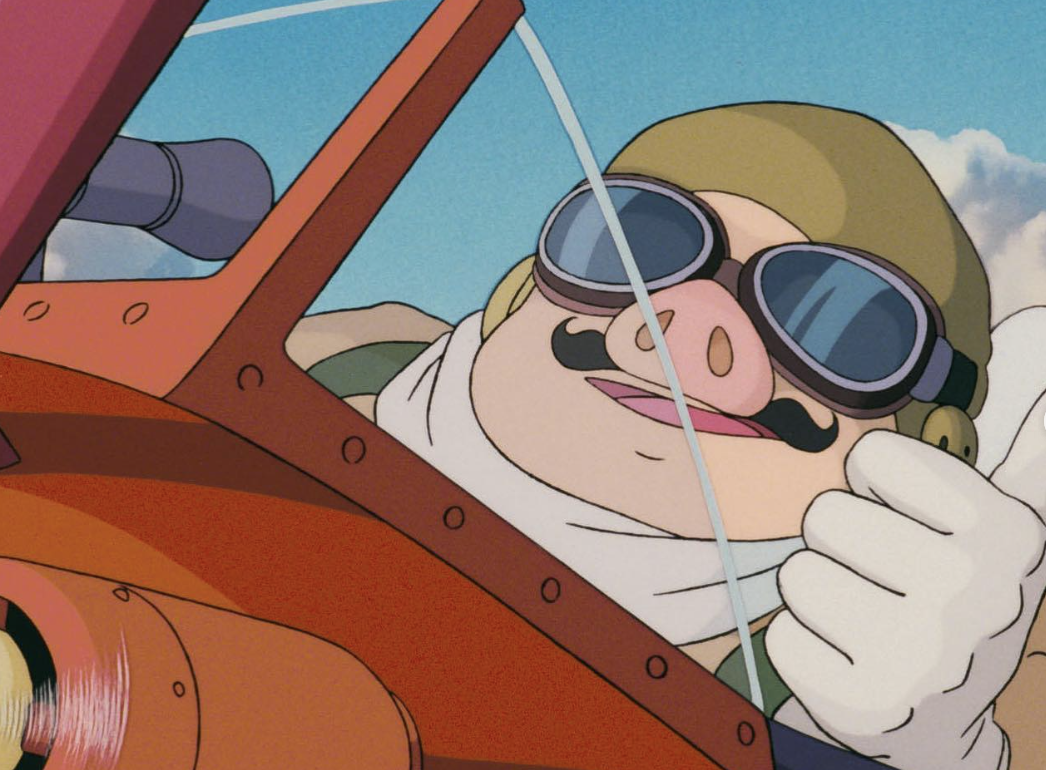

“I’d rather be a pig”: Amid fascism and a reckless AI arms race, Ghibli anti-war opus ‘Porco Rosso’ matters now more than ever

Recent Posts

The identity industrialists Lessons in connoisseurship from the Golden Globes “Suddenly everyone’s life got a lot more similar”: AI isn’t just imitating creativity, it’s homogenizing thinking Synthetic ‘Vtubers’ rock Twitch: three gaming creators on what it means to livestream in the age of genAIRelated Posts

AI Observer

David Z. Morris|Analysis

“Suddenly everyone’s life got a lot more similar”: AI isn’t just imitating creativity, it’s homogenizing thinking

AI Observer

Stephen Mackintosh|Analysis

Synthetic ‘Vtubers’ rock Twitch: three gaming creators on what it means to livestream in the age of genAI

AI Observer

Raphael Tsavkko Garcia|Analysis

AI actress Tilly Norwood ignites Hollywood debate on automation vs. authenticity

Arts + Culture

Dylan Fugel|Analysis

Dave Snyder is Partner + Chief Design Officer,

Dave Snyder is Partner + Chief Design Officer,