May 9, 2014

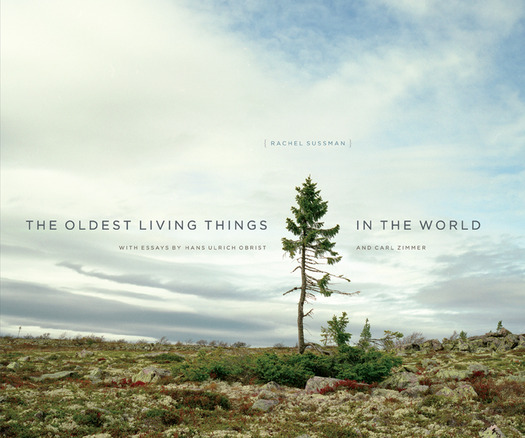

The Oldest Living Things In the World

With the recent release of a scientific study stating that climate change, once a fear for the distant future, is already upon us, Rachel Sussman’s glorious, and vitally important book, could not come at a more crucial moment.

Have you ever stood in awe of front of an old tree, aware that it has lived on the planet longer than you have? Or picked up a piece of coral and realized that it might be as old as your father?

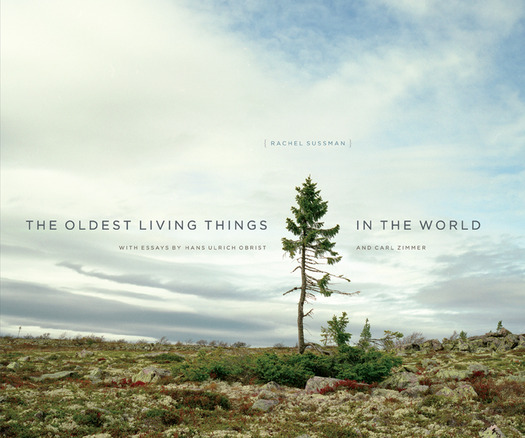

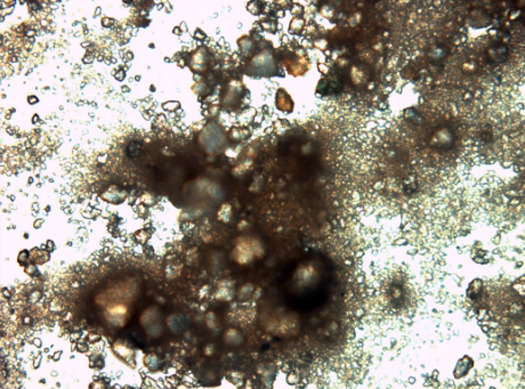

Now consider this: a 3,000 year old organism that grows one centimeter every one hundred years (which is slower than the rate at which the continents are currently drifting apart). Or the oldest predator of living things that is also one of the largest, at an astonishingly genetically continuous 2,200 acres, or three and half square miles. Or a tree, thought to be at least 13,000 years old, that has migrated its trunk and branches underground, leaving just a crown of its leaves peeking out, so that it is protected from the ravages of forest fires.

Map lichen R. Geographicum #0808-04A05 (3,000 years old, Southern Greenland) ©Rachel Sussman

These are not creatures from a post-apocalyptic bio-fantasy film. They are organisms that exist on our earth, now: they are, respectively, The Map Lichen of Greenland, the Honey Mushroom of Oregon, and the underground forest of South Africa. And they are just a few of the astonishingly old — as in over 2,000 years old — individual organisms that you can find in Sussman’s book The Oldest Living Things in the World.

With vision and dedicated persistence — think of a hip, female Shackelton — she has tracked down and brought these organisms to our awareness in lush photographs (taken with 6×7 film camera) and vivid text. The book is not a gimmicky safari in pursuit of the oldest living things but a nuanced, scientifically grounded, and aesthetically sophisticated journey into deep time: a trans-disciplinary exploration that weaves together art practice, scientific knowledge and what I can only call philosophy.

Although it has no overt political or environment agenda, her work has an urgency that is difficult to miss. It should be required reading because what we design, manufacture and consume directly effects these astonishing manifestations of life. The book makes abstract, and frankly boring global warming data viscerally, and visually, real: who are we to mess with the Siberian Actinobacteria, that has been alive and living underground in the permafrost for 400,000-600,000 years? (Sussman gives us some perspective: the cuneiform and the wheel, inventions that mark the birth of civilization, appeared only 5,500 years ago). What damage will a thaw in the permafrost unleash?

Along with environmental damage, these organisms are also threatened by good ‘ol human folly. The Senator, a cypress tree that was 3,500 years old, was a major tourist attraction in Orlando, Florida back before Walt Disney. Sussman visited the Senator in 2007, but was underwhelmed by the tree in the wake of some dramatic experiences in Africa. She figured she’d return to photograph the tree again when the time was right. But in January, 2012 the tree collapsed and died: the result of a fire that had been burning, unnoticed, in its hollow trunk for more than a week.

What was the cause of death for one of the oldest trees in the world? Some kids, high on meth, had snuck into the park and climbed inside the tree. They had lit matches or a lighter while doing their drugs and tree’s hollow trunk turned into a chimney.

For Sussman, the lesson was that “longevity can lull us into a false sense of permanence.” She became complacent about returning to Florida while planning and experiencing more exciting journeys to Greenland, or Antarctica. Florida was easy, close to home. She could go back anytime. But suddenly the tree was gone.

The story has a redeeming postscript. Clippings from the tree had been taken a number of years previously, and a forty foot grafted tree was recently planted on the Senator’s original location. It’s now thriving.

Sussman calls her photographs “portraits”, which might be stretching it a bit. But it is a rhetorical way to distance her work from the legacy of the Romantic painters of the nineteenth century who were drawn to the sublime — stupendous vistas of providential nature. Sussman’s objectives are less grandiose and more intimate. The best of her images reveal a startling individuality and oddness.

La Llereta #0308-23826 (up to 3,000 years old, Atacama Desert, Chile) ©Rachel Sussman

My favorite is the Llereta of northern Chile, which lives in one of the most arid places on earth. They are outrageously hyper-vivid green, and their forms are globular and bulbous: they look like moss on steroids but they are actually a shrub of tiny, densely packed branches. Clocking in at up to 3,000 years, they are distant relatives of carrots, parsley and celery who have adapted to extreme conditions.

By focusing our attention on organisms over 2,000 years old, Sussman’s work is an antidote to our culture of immediacy (the irony is that she is using photography to capture in milliseconds what took thousands of years to grow). It’s a reminder of the importance of thinking about “deep time” — an Enlightenment concept, derived from the study of geology, when the age of the origin of the earth was ratcheted back from a few thousand to billions of years. This was a revolutionary and disconcerting discovery. “The mind seemed to grow giddy by looking so far into the abyss of time” wrote one geologist in 1788.

Those words could just as easily apply to the organisms in Sussman’s book. Looking at the map lichen and pondering their one centimeter per one hundred year slow growth one does become giddy with the abyss of time, with what has survived and what has lived, and what will, with care and responsibility, continue.

Observed

View all

Observed

By Adam Harrison Levy

Related Posts

Graphic Design

Sarah Gephart|Essays

A new alphabet for a shared lived experience

Arts + Culture

Nila Rezaei|Essays

“Dear mother, I made us a seat”: a Mother’s Day tribute to the women of Iran

The Observatory

Ellen McGirt|Books

Parable of the Redesigner

Arts + Culture

Jessica Helfand|Essays

Véronique Vienne : A Remembrance

Recent Posts

Beauty queenpin: ‘Deli Boys’ makeup head Nesrin Ismail on cosmetics as masks and mirrors Compassionate Design, Career Advice and Leaving 18F with Designer Ethan Marcotte Mine the $3.1T gap: Workplace gender equity is a growth imperative in an era of uncertainty A new alphabet for a shared lived experienceRelated Posts

Graphic Design

Sarah Gephart|Essays

A new alphabet for a shared lived experience

Arts + Culture

Nila Rezaei|Essays

“Dear mother, I made us a seat”: a Mother’s Day tribute to the women of Iran

The Observatory

Ellen McGirt|Books

Parable of the Redesigner

Arts + Culture

Jessica Helfand|Essays